One of the weirder things to come out of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) “One Pill Can Kill” fentanyl awareness campaign is the agency’s determination to shoehorn it into family-friendly events. The campaign is increasingly popping up springtime traditions and fall festivals, warning of “fentanyl-laced” pill distributors targeting unsuspecting teenagers over Snapchat. The DEA has organized its public messaging almost entirely around that concept, which is how it recently it ended up sponsoring an esports tournament.

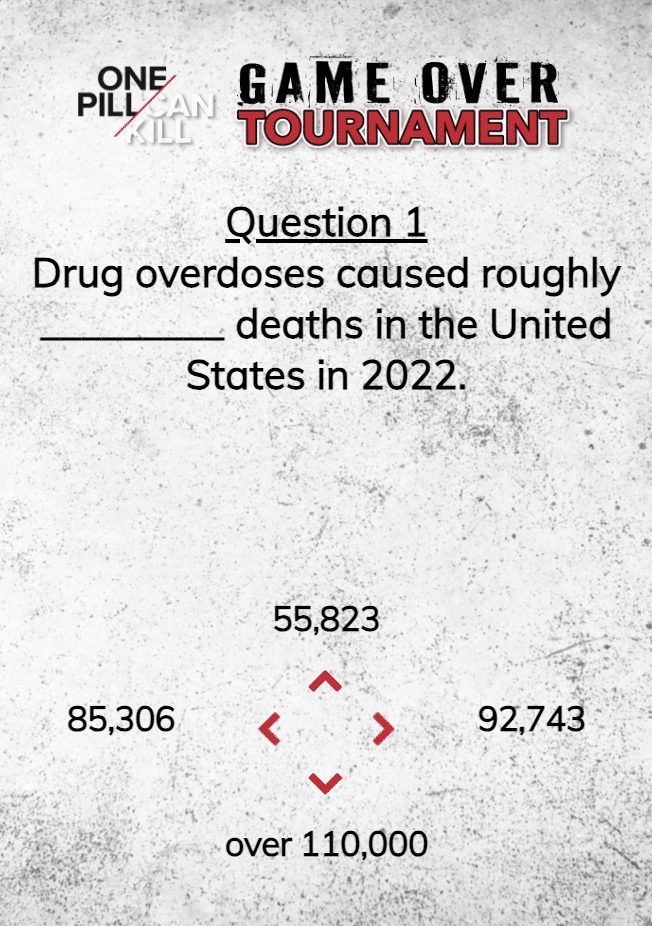

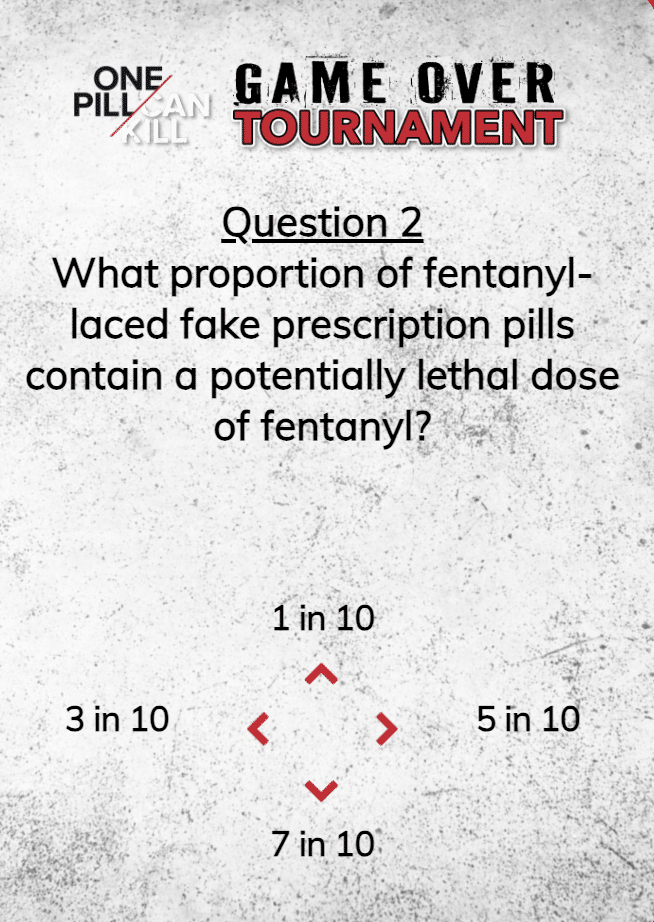

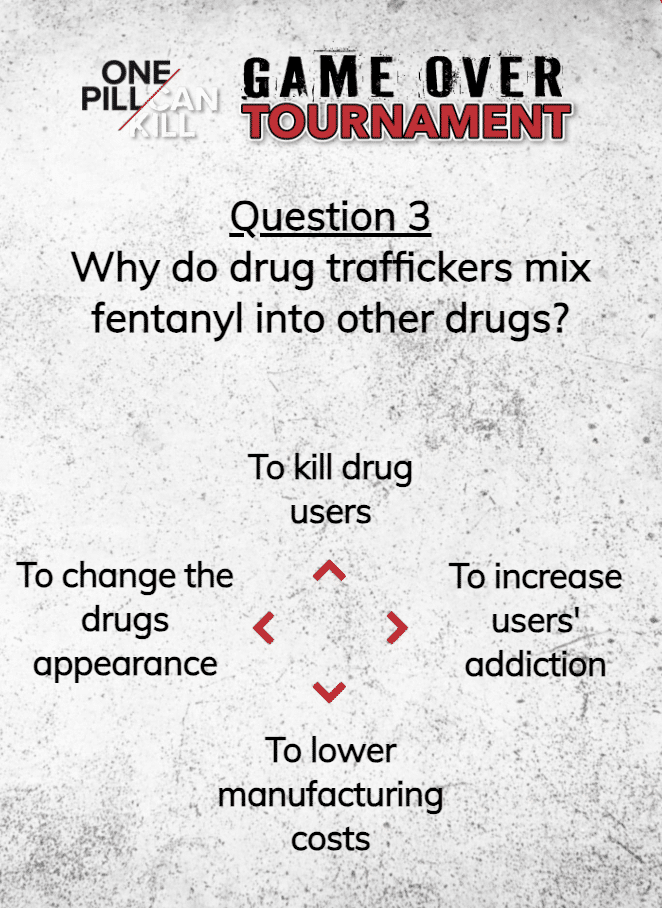

The tournament part of the “One Pill Can Kill Game Over Tournament,” where DEA guest commentators shared fentanyl misinformation soundbites while college students played Rocket League, was livestreamed January 27. For spectators who want to test their fentanyl knowledge, the DEA made an accompanying quiz.

If you feel a bit sick each time the agency responsible for mass overdose death hypes its “fun and informative” questions, you will probably feel a bit sicker each time it promises that lucky winners get an Xbox. The quiz is, regrettably, still online until February 4. Thankfully there are only six questions.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated 109,680 overdose deaths between December 2021 and December 2022. Not all of them were necessarily overdoses, and many deaths that were caused by overdose have inevitably been left out of the official number.

For what it’s worth, the statistic that would have been more relevant to the task at hand is 73,654, the CDC estimate for fentanyl-involved deaths—as opposed to deaths involving any drug—in the same time period. But it’s not like fentanyl awareness is actually what the DEA is going for here.

The first sentence is going to come up again in a later question so we’ll address it there. But even if it were accurate, the second sentence is claiming that all counterfeit pharmaceuticals are fentanyl-based.

The thing about the DEA focusing “One Pill Can Kill” overwhelmingly on students is that if the agency were drug-checking counterfeit Adderall pills and finding fentanyl, the forensics results would probably be up on billboards. It would be on the morning news. Counterfeit Adderall is still meth, at least for now.

I actually got this one wrong, at least according to the DEA; I went with “To lower manufacturing costs.” Which seemed equally plausible, since the agency is heavily invested in the narrative that fentanyl doesn’t just kill “addicts,” but the completely separate category of people represented by promising young students.

Transnational drug trafficking organizations don’t deliberately “mix fentanyl into other drugs.” It doesn’t make teens or anyone else more fentanyl-aware to leave them with the impression that the opioid supply is essentially heroin with some fentanyl sprinkled in, or that fentanyl is added to all illicit drugs indiscriminately. It just makes people think of drug selling and drug trafficking as the same. Which is actually what the DEA is going for here.

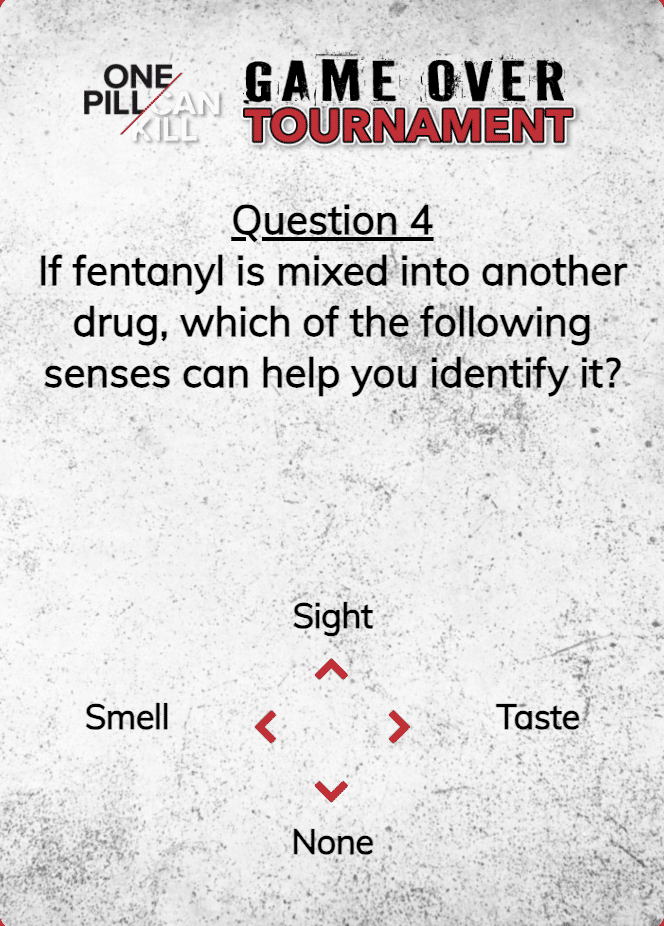

A defining feature of “One Pill Can Kill” is that it mostly just recycles the same four or five talking points over and over, but whenever it has a natural opportunity to share something useful it makes a concerted effort not to. Your senses alone can’t identify fentanyl but they can absolutely help, and in many situations they might be all you have.

Rainbow fentanyl is an obvious example of how visual cues might help someone looking for pharmaceutical oxycodone avoid counterfeit versions. In a lot of fentanyl pressed pills, the etching isn’t as crisp as what you see if you Google authentic versions of what you’re trying to buy. This doesn’t mean that if the etching looks believable enough then the pill is authentic—if it didn’t come directly from a pharmacist, just assume it’s counterfeit.

This information isn’t necessarily relevant to people who already know they’re using illicit opioids and seek out fent pressed pills because that’s just what’s available to them, but it would be useful to teens searching for actual pharmaceuticals over Snapchat.

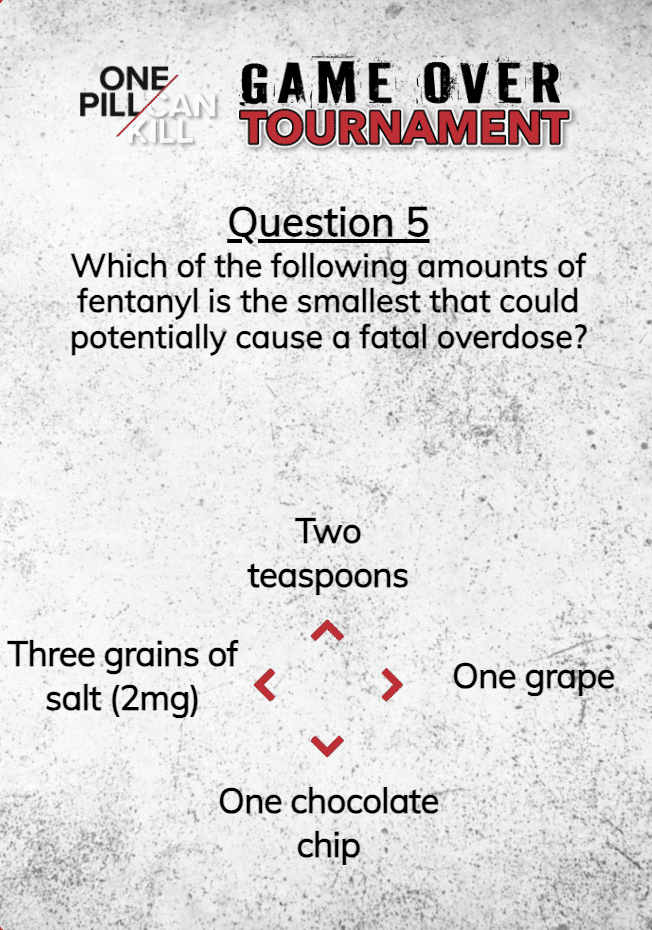

This is the “lethal dose” from Question 2. A few years back the DEA decided that 2 mg of fentanyl was the OD threshold for opioid-naive adults, a concept it’s gotten a lot of mileage out of since then. Despite the counterintuitive approach to the overdose crisis, “One Pill Can Kill” is aimed at people who don’t use drugs on a day-to-day basis. Claims like this one helped the agency to further separate acceptable losses (opioid users) from innocent victims (teens and children), while being too reductive to really be useful to anyone.

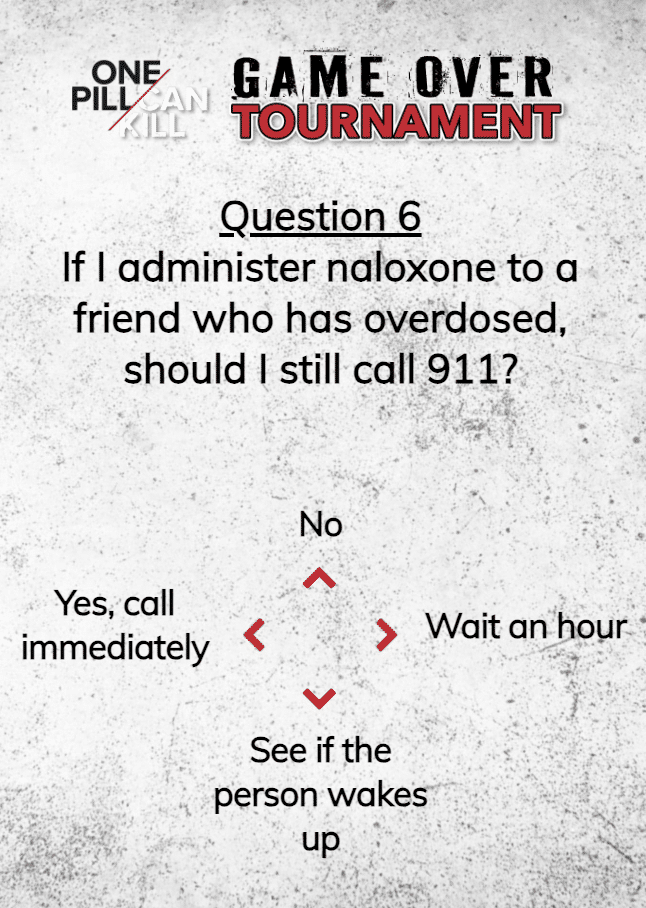

This is neither fun nor informative. This is wrong. Naloxone’s effects peak in about 30 minutes, but the reason someone who was just revived with naloxone might still be at immediate risk of overdose isn’t that the naloxone is about to wear off. It’s that high doses of naloxone will precipitate withdrawal if the person has an opioid tolerance, and they might attempt to alleviate that pain by using more opioids and overdosing again.

“Stronger opioids,” including fentanyl, do not need more naloxone than any other opioids. One dose is usually enough, and you don’t need a second unless the first was administered at least two minutes ago to someone who has not yet woken up. It’s natural to be scared, and to feel like two minutes is way too long to wait. But pumping more naloxone into someone’s system—before the first dose has had a chance to work—won’t make it work any faster or better, and may cause unnecessary suffering.

There are a lot of different circumstances under which people administer naloxone, and in many of them calling 911 is going to make things worse, by adding cops. If you do call 911, you can just tell them there’s a medical emergency and give them your location, then hang up. Telling them that the emergency is a drug overdose will probably just summon cops to the scene all the more quickly, and the paramedics will come at the same speed with the same equipment either way. Including more naloxone.

Show Comments