Up through 2021, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) national drug use survey didn’t include illicit fentanyl. It does now, which has not improved the situation. According to the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), no one with opioid use disorder (OUD) uses illicit fentanyl and about half the fentanyl being “misused” is the kind that comes from a doctor.

The annual NSDUH covers mental illness, substance use, treatment and recovery for people ages 12 and up. The 2022 NSDUH, published November 13, reached 71,369 respondents in person and online. They were asked about their use of various regulated, controlled and illicit substances within the past 12 months. They were then were shown the corresponding DSM-V criteria for substance use disorder (SUD) and asked which, if any, applied to them.

People who selected at least two, which for 2022 was 17.3 percent of respondents, were categorized as having SUD. However, none of the data collected on illicit fentanyl were counted toward SUD figures. Respondents weren’t asked about illicit fentanyl until the end of the survey, after they’d already completed the SUD section.

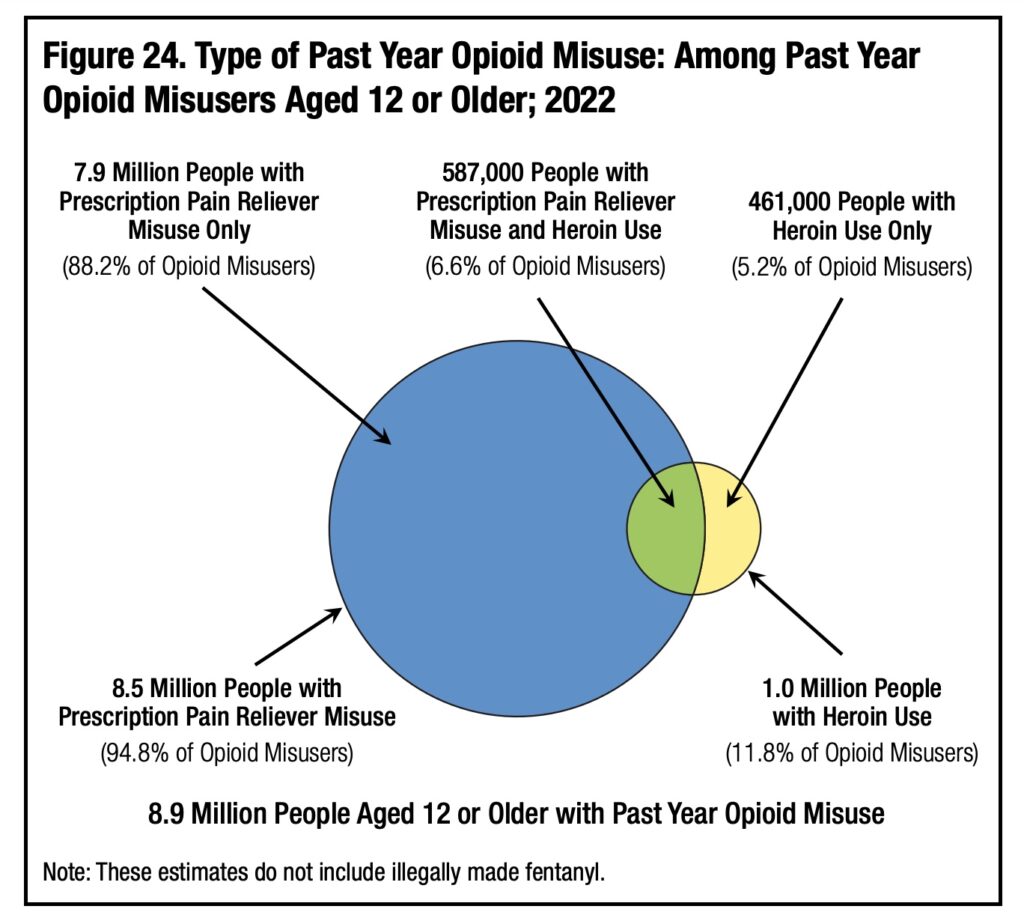

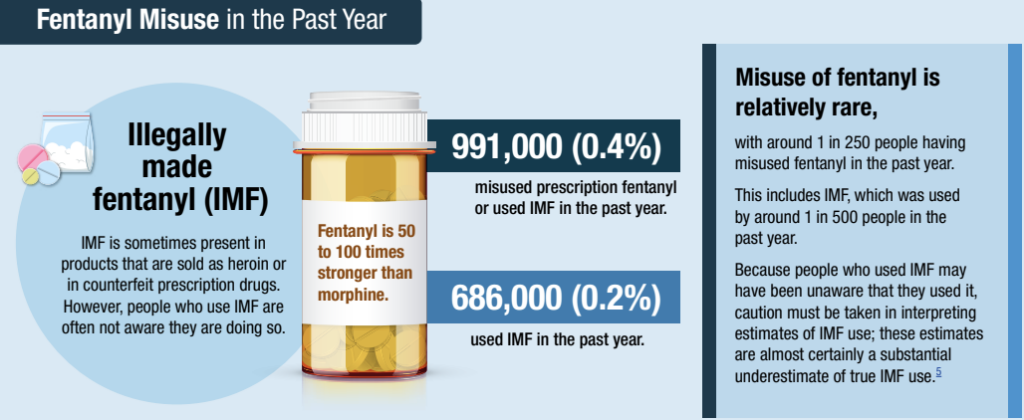

The only fentanyl that made it into estimates of SUD, opioid use disorder (OUD) and “opioid misuse” is prescription fentanyl. Some respondents probably logged illicit fentanyl as heroin because that was the option closest to what they actually use, whether or not they prefer it. The NSDUH says the omission isn’t a big deal because based on its estimates, only about 0.4 percent of the population aged 12 and up use fentanyl of any kind at all, and only 0.2 percent use “illegally made fentanyl” (IMF).

“For data from people who used IMF in the past year to affect SUD estimates in NSDUH, respondents would need to have used only IMF or to have attributed their SUD symptoms to IMF and not to their use of other substances,” it states, dismissing that population as statistically insignificant.

It takes an inordinate amount of fine print to collate data on US opioid use in a way that leaves out illicit fentanyl, but SAMHSA has managed to do it.

Despite the federal government’s insistence on conflating the “opioid epidemic” with addiction, SAMHSA leaving illicit fentanyl out of the SUD data actually makes sense. The focus is squarely on prescription opioids, and the government has long been more interested in OUD and overdose whenever it can put white, middle-class victims at the center of the narrative.

The NSDUH states that 3.2 percent of respondents “misused” opioids, and that the “vast majority” of this involved prescription painkillers. Authors somehow found a way to count non-opioid analgesics toward that total, but not illicit fentanyl. Of course, that isn’t to say fentanyl isn’t in there; pharmaceutical fentanyl is on the list of prescription painkillers.

More to the point, the survey language doesn’t account for the fact that many low-income people who know they’re using fentanyl would still identify as heroin users. Or for any number of other reasons why the data on heroin use is too reductive to be useful to anyone.

“Caution must be taken in interpreting estimates of IMF use” is the kind of boilerplate disclaimer you add when the people you answer to are grant funders and data review boards, and not the people who contributed the information. In future NSDUH, caution should probably be taken while the drafting process, rather than after it’s published, but if SAHMSA’s concerned with giving skewed results then it’s got bigger problems.

Among other exclusions, the NSDUH is only offered to people who are documented citizens with fixed addresses—except for everyone with very fixed addresses, due to being incarcerated. So when it says that 41.1 million people in the US smoke cigarettes, what that actually reflects is about 14.6 percent of respondents to a survey that was never sent inside prisons, where smoking prevalence is highest. When it says 21.5 million adults over 18 have co-occurring mental illness and SUD, that’s 8.4 percent of a sample that didn’t include anyone institutionalized in psychiatric wards or in residential treatment centers.

The rest of the NSDUH isn’t any less fraught than the fentanyl questions; those are just what’s new. Some issues would have been relatively easy to preempt. Meth, for instance, also exists in both illicit and prescription versions. The NSDUH states that “most methamphetamine used in the United States is produced and distributed illicitly rather than through the pharmaceutical industry.” Which is correct, and somehow did not preclude meth from appearing in the SUD numbers.

Top image via California Department of Public Health. Inset graphics via SAMHSA.

Show Comments