There aren’t any treatments for stimulant use disorder (SUD) that have strong evidence, but the one that has the most evidence is contingency management (CM).

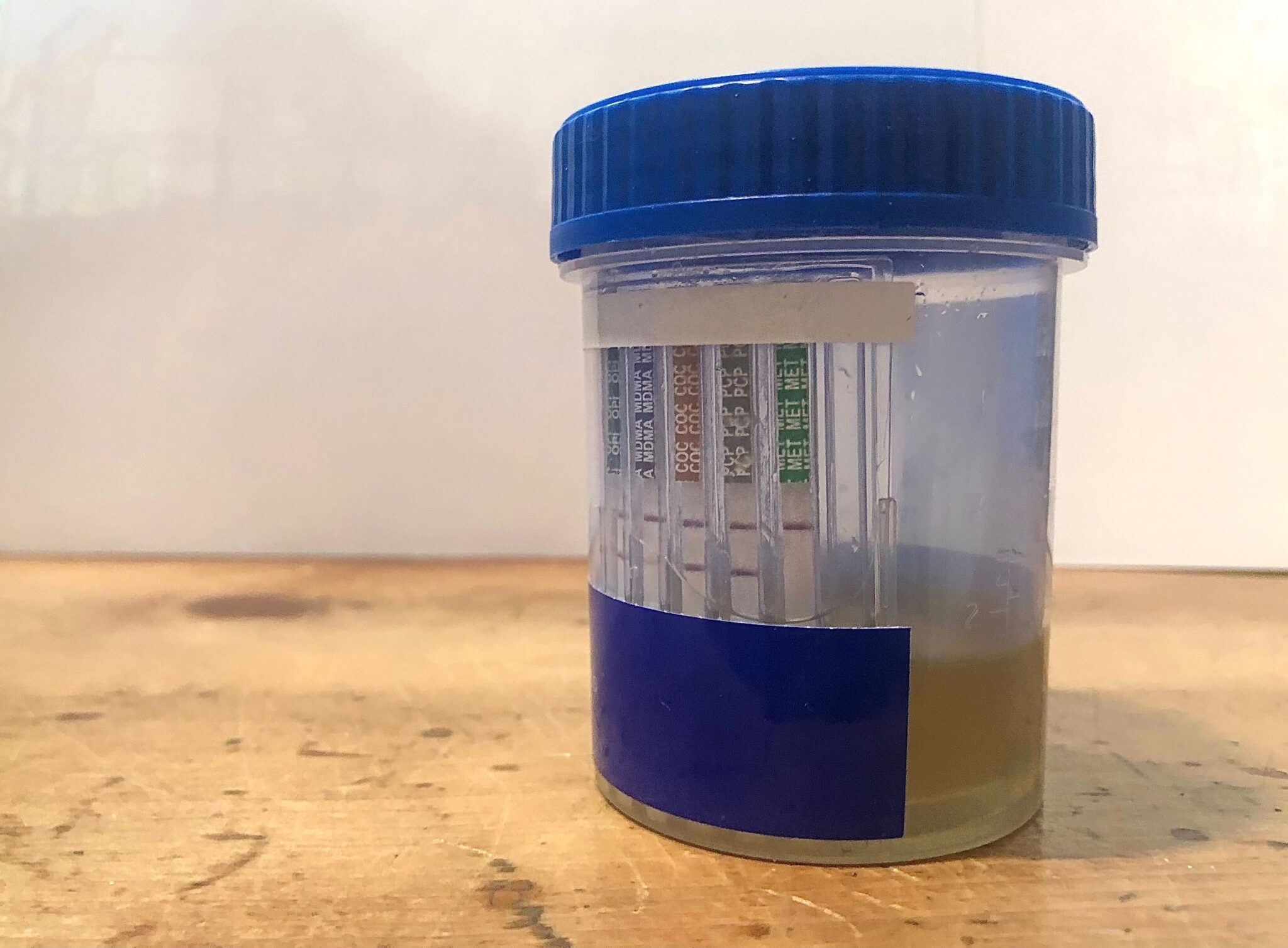

CM is based in the idea of positive behavioral reinforcement. Two or three a week you go to a clinic and pee in a cup, and if the results are negative for cocaine and methamphetamine you get some small incentive like a $10 gift card. Some programs use different structures, but generally if the urine sample is negative for stimulants at consecutive appointments, then the incentive value goes up a teeny increment. If the results are positive for stimulants, or you have an unexcused absence, the value resets.

Some programs offer peer support and don’t require participants produce stimulant-negative urine drug screens (UDS) if they want to keep showing up even without the incentives. But often CM is pretty infantilizing, what with the baked-in premise that drug users are not to be trusted with money.

Everything about CM is designed around abstinence. Some CM programs for other behaviors, like cigarette smoking, use tests that can measure decrease in use. But cocaine and methamphetamine programs all hinge on UDS, which only measure use as “Yes” or “No.” In a paper published April 16 in the journal Addiction, researchers argue that it’s time to modify stimulant CM for harm reduction.

“Given rising prevalence and lethality of stimulant use, the preference for harm reduction versus abstinence-only approaches and substantial research showing the efficacy of CM, we propose that it is time to consider updating CM protocols,” the paper states. “Additionally, rising and more lethal stimulant use lends urgency to the need to make CM widely accessible.”

The proposed changes include making UDS easier for providers to access, developing new ways to monitor changes in use, not resetting the incentives as low in the event of “relapse,” and a robust marketing campaign—commercials, infographics—to increase demand.

Urine drug screens aren’t conducive to measuring changes in drug use.

The main barrier to CM being widely accessible is bureaucratic, and it’s unclear whether a harm reduction version would move things along any faster. A lot of providers rely on State Opioid Response funding, and while SAMHSA allows those grantees to put the funds toward CM it also caps the incentives at $75 per participant. CM programs are time- and labor-intensive to complete, and don’t really produce results when they can’t offer participants at least a few hundred dollars. Medicaid doesn’t cover CM, and so far the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services has only approved reimbursements for programs in California, Washington and Montana.

A lot of the other barriers are related to the UDS. CM involves much more frequent testing than what Medicaid would cover. Even as more states get CM approved for Medicaid coverage, providers have to apply for a FDA laboratory waiver in order to get reimbursements for administering the tests.

Beyond that, UDS themselves just aren’t conducive to measuring changes in someone’s drug use over time. Urine testing is qualitative, not quantitative—the results don’t indicate how much of a substance is detected, just whether it’s there or not.

A harm reduction CM program wouldn’t need harm-reduction versions of drug tests. It would get rid of them.

The authors noted that in some CM programs for cigarette smoking, reduction in use had been measured through carbon monoxide detection during breath sampling. They called for “investing in research to develop rapid point-of-care tests that can detect reductions in stimulant use in addition to abstinence, which would allow CM protocols to incentivize both, albeit to differing degrees.”

Aligning with harm reduction principles doesn’t mean lowering barriers to UDS so they’re more accessible to providers, or developing oral fluid tests to monitor changes in use. A harm reduction CM program wouldn’t need harm-reduction versions of drug tests. It would get rid of them.

A CM program modified for harm reduction would probably incentivize appointment retention, then give people transportation vouchers and not penalize them for appointments they miss. It would include education on safer stimulant use, or how to respond to overamps, or how to properly dilute stimulants when using fentanyl test strips to avoid the false positives issue. It would also ask participants their goals, rather than assign them.

“Incentivizing outcomes such as attendance or harm reduction activities in addition to abstinence also has downsides,” the authors state in the paper. “Specifically, incentivizing multiple behaviors at the same time can decrease CM efficacy and increase both incentive costs and protocol complexity, such that CM is more challenging to implement and requires additional clinician training and supervision.” They conclude more research is needed.

Nothing about CM actually requires UDS. Its basic principles are about positive reinforcement. The reason it’s difficult to conceive of a program incentivizing anything other than abstinence is that ideologically, stimulant CM is rooted in the drug-testing more than in the incentives.

Abstinence frameworks are often friendly toward harm reduction because they confuse it with use reduction.

Many people do have good experiences with CM, but broadly speaking there’s a lot more enthusiasm for these programs in academia and public policy than there is among participants. Can we take a treatment structured entirely around abstinence and, with enough research and labor and advertising, contort it into something slightly closer to harm reduction? Sure. But … why.

Despite the narrative of an increasingly lethal stimulant supply, it’s a shaky conclusion to draw from overdose mortality data. “Stimulant-related” or “stimulant-involved” deaths don’t mean stimulants were the underlying cause. More people are using stimulants than they were a few years ago, so more people have stimulants in their system at the time they die. There are definitely some people dying as a direct result of stimulant use, but not the way academia and media and law enforcement make it sound.

Some of the opening statistics from the Addiction paper, for example, cite data on the growing subset of overdose deaths that involve fentanyl. In 2021, 47-ish percent of fentanyl deaths also involved stimulants. Overdose from stimulants alone, meanwhile, had “remained relatively more stable, from 14.8 percent in 2010 to 17.9 percent in 2021.”

The Addiction paper characterizes this by saying the “mortality rate associated with stimulant use has increased 50-fold,” and that “stimulants alone or in combination with fentanyl” were involved in nearly half the overdose deaths recorded in 2021.

Tere’s not much appetite for stimulant agonist medications because the broader public does not like the idea of stimulant users having stimulants.

A lot of the claims, both about the lethality of stimulants and the efficacy of CM, present the data similarly. The authors told Filter that they “believe that these are accurate statements given the evidence presented.” This isn’t egregious, because it’s the norm to cite stimulant data this way.

There are a bunch of reasons the Food and Drug Administration hasn’t approved any SUD medication equivalent to methadone or buprenorphine—stimulants are pharmacologically more complex than opioids, their withdrawal process less visible—but one reason is the level of hate and fear is stoked around cocaine, and especially meth. There’s not much appetite for stimulant agonist medications because the broader public does not like the idea of stimulant users having stimulants. So now the public thinks that fentanyl is in everything, but that just as many people are dropping dead from stimulants alone, and that the most promising thing we can offer them is a short-term abstinence intervention that doesn’t address anything else going on in their life.

Abstinence frameworks are often friendly toward harm reduction because they confuse it with use reduction. But harm reduction is effective because it’s premised in safer use, and the understanding that people need more than one thing at a time, especially if their use has increased. Which is different than collecting bodily fluids and telling anyone whose use has gone up that they don’t get a prize.

Photograph via Kastalia Medrano

Show Comments