For children like me who grew up in Richmond, California, our lived experiences are very different than our peers who grew up just miles away in the affluent Bay Area.

In Richmond, you see everything from gangs and gun violence to drugs and homelessness. Speaking from personal experience, it is very common to lose someone you know to gun violence in Richmond—it’s almost a normal part of growing up here. Unfortunately, young people in my community and similar communities are not always given the proper tools to learn how to deal with these difficult situations and how to cope with trauma.

Despite everything that happens to young people in my community, something that is not talked about with us enough is the idea of “mental health.” I did not know what mental health was until I started my internship at RYSE Youth Center in Richmond, when I was a junior in high school.

One thing I realized quickly when I started to learn about mental health was that we need to have better conversations around how youth in places like Richmond cope with stress and trauma.

When talking about coping strategies, young people are often blamed for the way they choose to deal with their everyday traumas, such as smoking marijuana. Many people fail to recognize that youth from low-income communities of color may not always be able to access different mental health resources and coping strategies.

I had the opportunity to explore the issue of youth drug use as a coping strategy as part of a youth participatory action research project at the RYSE Youth Center, which was recently published in the Journal of Family Violence.

One finding was that marijuana was utilized the most by the youth as a coping strategy because it was the most accessible option.

My fellow youth researcher and I saw that a primary coping strategy used to deal with stress and trauma was marijuana, which was not surprising. However, we wanted to further understand why so many youth in our survey chose to utilize this particular coping strategy, and what were the flaws in alternatives—such as counseling or sports programs—that made marijuana the most common option among our subjects.

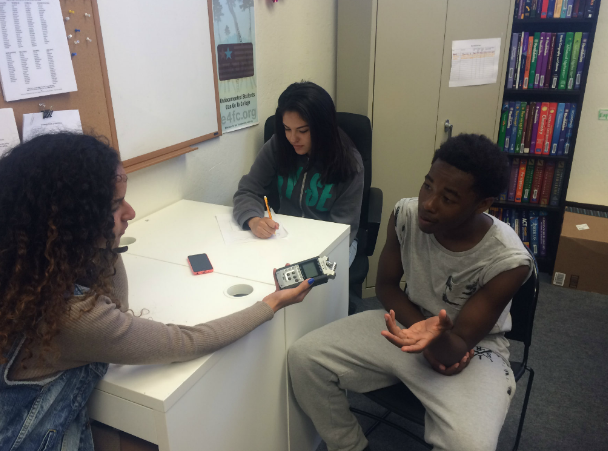

Our quantitative data included 100 surveys from youth aged 13 to 21 about their coping strategies. We also believed that another approach was important to our research. Although data collection is important, the written and oral stories behind those numbers can bring the data to life and create a narrative from those numbers, since our community is much more than statistics. Our qualitative data included a focus group of 12 young people, as well as five in-depth individual interviews (pictured above).

One finding was that marijuana was utilized the most by the youth as a coping strategy because it was the most accessible option. Many of the youth identified that it was easy to buy, and could be found on the corner of their street or even in their own homes.

Many youth said that talking to adults was potentially more harmful than smoking marijuana.

What struck me most about the findings of my research was not the fact that the youth in Richmond smoke marijuana, but why they chose to utilize weed more than any other coping strategy, such as talking to adults.

Many youth said that talking to adults was potentially more harmful than smoking marijuana. While some seemed to identify that talking to adults can be helpful, more often than not, it was perceived to be harmful because they tend to judge youth, don’t always know how to communicate with them, and are not always good at understanding their circumstances. Those surveyed felt that adults, who should be the most accessible resource for youth, can potentially exacerbate the trauma and stress that youth encounter.

Richmond has long been known for its high crime rate, gang and gun violence, drug-related violence, low graduation rates and other statistics that at one point led to the city being labeled as one of the most dangerous in the US. Most of the problems within the community are attributed to youth by other community members. These issues are so prevalent in our lives that we normalize them, yet we never find a proper way of coping with them.

During my research project, I realized that my city is hurting, and instead of getting help, we are being criminalized for dealing with the traumas in our lives in the way that makes the most sense to us. There are many policies put into place, like “zero tolerance” drug policies at schools, that put the blame on the individual rather than searching for the root cause of our behaviors. Policies like these do not work and only add to the trauma that we already experience outside of school.

We started a program called “Chat Lounge,” a safe space for members to discuss important issues without adults present.

When we conducted interviews with youth, we heard some ideas about what young people want to help them cope. For example, youth would like to see more money invested into safe spaces for young people, like RYSE, and to have better training for service providers on how to interact with youth, involving harm reduction and trauma-informed care models.

After we heard those ideas, we decided to put them into practice as part of our research action plan. We started a program at RYSE called “Chat Lounge,” a safe space for members to discuss important issues without adults present. We did not want the group to be overly structured because we wanted the conversations to be as natural as possible.

Discussion topics varied depending on what the members wanted to talk about, but were focused on three different types of oppression—institutional, interpersonal and internalized.

For example, we talked about police brutality in our community, and a number of young people shared their different experiences with the Richmond police. At the end of this particular session, one member who participated told us that getting to talk about their experiences out loud was very helpful, and that it was comforting to know that they were not being judged.

If we want to see youth thrive and become successful—especially in neighborhoods similar to Richmond, where the odds are against us—it is important to provide them with opportunities to create spaces and communities that will work best for and with them. It is important to start positive coping strategies at a young age so that we can heal properly.

This story is co-published with The Chronicle of Social Change, a nonprofit news publication that covers issues affecting vulnerable children, youth and their families.

Image credit: The Chronicle of Social Change

Show Comments