“We call on social justice movements to develop strategies and analysis that address both state AND interpersonal violence, particularly violence against women. Currently, activists/movements that address state violence (such as anti-prison, anti-police brutality groups) often work in isolation from activists/movements that address domestic and sexual violence.” Those words were written in 2001 by prison abolition organization Critical Resistance and INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence.[1]

The past 17 years have seen an increase in prison abolition groups and organizing. In stark contrast to prison reform advocates, who push to improve prison conditions but posit that prisons are ultimately necessary for societal safety, prison abolitionists charge that prisons themselves are sites of violence and can never be adequately reformed. Instead, prisons must be eliminated; so too must the conditions that send people to prison, including racism, poverty and root causes of violence.

Conspicuous by its absence in many of the conversations about prison abolition, however, is how to address gender-based violence and harm without relying on police and prisons.

At the same time, many of the most prominent organizations and movements fighting domestic and sexual violence continue to rely on policing and prisons. In the aftermath of the six-month prison sentence imposed upon Brock Turner, the white Stanford student convicted of sexually assaulting an unconscious woman, feminist groups and activists expressed outrage at the shortness of the sentence and called for the ouster of his sentencing judge.

Harsher punishments and lengthier sentences have always fallen hardest upon—and devastated—people and communities of color, while providing little safety or prevention from gender violence.

Similarly, as accusations against celebrities like Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby mounted, calls for justice centered arrest and prison. The most vocal calls for “justice” failed to recognize that harsher punishments and lengthier sentences have always fallen hardest upon—and devastated—people and communities of color, while providing little safety or prevention from gender violence.

This reliance on criminalization reinforces state violence, which is not only perpetrated against overwhelmingly black and brown and poor men, but also upholds a system punishing women (cisgender and trans), trans men, gender non-conforming and intersex people, even when they themselves are victimized by violence. We’ve seen this in the case of Marissa Alexander, the Florida mother initially sentenced to 20 years in prison after firing a warning shot to stop her abusive husband’s assault. We’ve seen this in the case of Ky Peterson, a black trans man currently serving a 20-year prison sentence after fatally shooting the man who raped him.

How did we get to this divide?

In 1994, Congress passed the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), which pushed police to respond to complaints of domestic violence, sexual assault and other gender-based violence. The act was the result of years of lawsuits and organizing by many feminists to force law enforcement to respond to gender-based violence rather than dismissing it as an interpersonal issue. In many jurisdictions, VAWA resulted in mandatory arrest laws and more punitive prison sentences. It also led to policies such as dual arrests, in which police arrested both people. Some jurisdictions jail victims as material witnesses or impose fines and threaten a survivor with arrest if they do not cooperate with prosecution. (The city of Columbus, Georgia, changed its policy of non-cooperation fines and arrests after a lawsuit by abuse survivor Cleopatra Harrison and the Southern Center for Human Rights.)

By and large, carceral feminism views solutions to gender-based violence through a white middle-class lens.

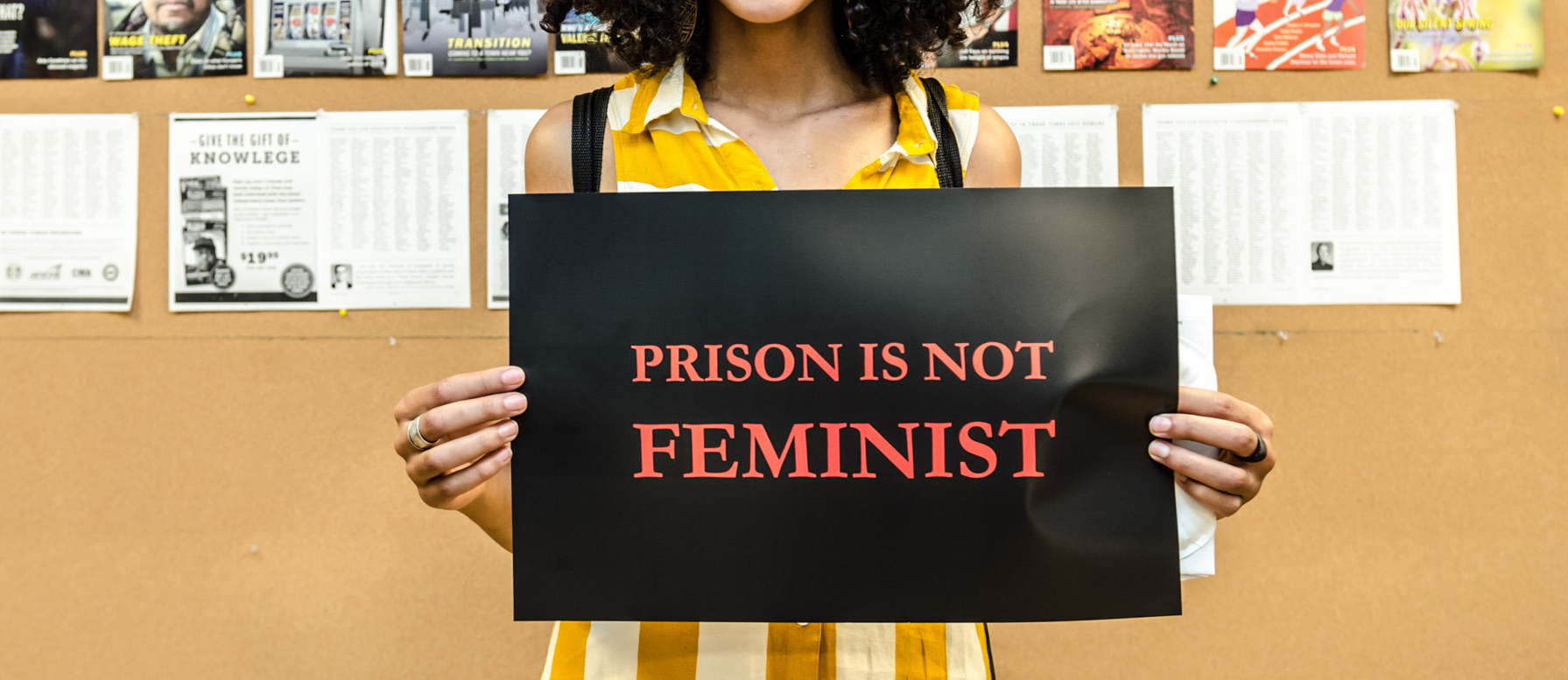

Carceral feminism is the term often used to describe this reliance on increased policing, prosecution and imprisonment as the primary solution to gender-based violence. By and large, carceral feminism views solutions to gender-based violence through a white middle-class lens, one which ignores the ways in which intersecting identities, such as race, class, gender identity and immigration status, leave certain women more vulnerable to violence, including state violence.

At the same time, women’s incarceration has skyrocketed. In 1980, the nation’s jails and prisons held 25,450 women; 10 years later, that number had nearly tripled to 77,762. By 2000, that number had doubled again to 156,044 and continues to grow. As of 2017, jails and prisons incarcerate 209,000 women. (These numbers do not include women in immigrant detention or youth jails or trans women in men’s jails or prisons.) At least half of incarcerated women reported surviving violence even before being arrest.

It’s still also true that nearly 90 percent of incarcerated people are men (or classified as men). But not every feminist and anti-violence activist espouses a carceral solution. For years, anti-violence activists and organizations, such as Beth Richie and INCITE! , have argued that increased criminalization replaces abuse by an individual with abuse by law enforcement, courts and prisons while doing nothing to address the root causes of violence against women. We’ve seen this with Marisa Alexander, Ky Peterson and countless other women and trans people.

No one knows how many thousands of survivors are sitting behind bars after law enforcement failed to guarantee their safety. That’s because no agency tracks this data. The most recent statistics are nearly 20 years old, from a 1999 Department of Justice report stating that nearly half of women in local jails and state prisons had been abused prior to their arrest. But, because women make up approximately 10 percent of the nation’s prison population, many of the conversations about mass incarceration and prison abolition continue to center men, a focus that leads to a false binary in which men are incarcerated and women are victims. It’s a divide that excludes people (of any and all genders) impacted by both interpersonal and state violence, and thus fails to meet their needs.

I’ve interviewed numerous adult survivors of domestic violence imprisoned for defending themselves. Again and again, they tell me that they turned to the police and legal system, both of which failed to protect them. Perhaps the police took their abuser away for a few days, but that didn’t stop the violence. Perhaps the courts issued an order of protection, a piece of paper that their abuser flagrantly ignored. Perhaps the police did nothing. Perhaps their abuser was the police. This same legal system that failed to protect them then punished them for their survival. In prison, many are subject to violence—at the hands of other incarcerated people, staff members or the day-to-day practices.

At the same time, much prison abolition organizing continues to reflect larger society’s failure to consider the societal and cultural shifts needed to end gender-based violence or to develop concrete ways to prevent and address domestic and sexual violence in daily life.

“The two are not really talked about together,” says Hyejin Shim. Shim works at the intersections of gender and state violence, as both a staff member at the Asian Women’s Shelter and an organizer with Survived and Punished, a grassroots group supporting criminalized and incarcerated survivors of gender-based violence. Though efforts to end gender-based violence and prison abolition are often positioned as incompatible, Shim notes that “both are focused on ending violence,” whether that violence is from an individual, the state or both.

Transformative Justice

One way to address interpersonal violence without relying on state violence is through transformative justice. Transformative justice refers to a community process that addresses not only the needs of the person who was harmed, but also the conditions that enabled this harm. In other words, instead of looking at the act(s) of violence in a vacuum, transformative justice processes ask, “What else needs to change so that this never happens again? What needs to happen so that the survivor can heal?” There’s no right or wrong set of footprints to follow in transformative justice; instead, each process depends on the people and circumstances.

Shim notes that people frequently engage in transformative justice processes, even if they don’t use that term. They come together to support people in their circles who have been harmed—helping them identify what they need and how to access those needs. At the same time, Shim points out that these kinds of skills are often undervalued in organizing circles. “In movement spaces, you might have a direct action training or a facilitator training, but not one for skills to work through conflict or support survivors,” she noted. In this #MeToo moment when more people are coming forward with their own experiences of sexual and domestic violence, “the support needed is not really there or been developed.”

Anti-violence organizers have developed resources to help fill those gaps. Creative Interventions, an organization dedicated to providing “resources for everyday people to end violence,” has developed a 608-page on-line guide of strategies to stop interpersonal violence. Organizers and abuse survivors Ching-In Chen, Jai Dulani and Leah Lakshmi Piepnza-Samarasinha compiled a 111-page zine entitled “The Revolution Starts at Home” (which later became a book), documenting ways that social justice organizers have held abusers accountable.

Creative Interventions’ guide, for example, recounts the way a Korean cultural community center in Oakland, California handled an incident of sexual assault, made even more complicated by cross-cultural factors.

In the summer of 2006, the Oakland center invited a drumming teacher from South Korea to teach at a week-long drumming workshop. One night, he sexually assaulted one of the students. The Oakland center handled the process through a series of actions, beginning with an immediate telephone call to the head of the drumming center in Korea. Even though it “was culturally difficult for the Korean American group to make demands of their elders in Korea, everyone decided this was what needed to be done.”

After the Korean institution took responsibility and apologized, the Oakland center sent a list of demands, including that the Korean institution establish sexual assault awareness trainings for their entire membership, a commitment to send at least one woman teacher in their future exchanges to the U.S., and a request that the teacher step down from his leadership position for an initial period of six months and attend feminist therapy sessions directly addressing the assault.

The Oakland organization also took actions on their part, including providing a set of sexual assault awareness workshops for the center members and members of other local drumming groups, and dedicating their upcoming festival to the theme of healing from sexual violence. With consent from the victim, facts regarding the incident were printed in the program “as a challenge to the community to take collective responsibility for ending the conditions perpetuating violence including collusion through silence.”

“Some people asked us later why we didn’t call the police. It was not even a thought in anybody’s mind.”

The story has far from a perfect ending; the victim (as she preferred to be called, rather than “survivor”) never returned to the cultural center; the lengthy process of both institutional reflection and engagement “sapped the energy and spirit of the organization and the friendships that had held it together;” and, while the drumming teacher returned to participate in festivals in South Korea, he was viewed with resentment and suspicion by Korean American visitors. But when Liz, the center’s president, reflected later on the series of events, she said: “Some people asked us later why we didn’t call the police. It was not even a thought in anybody’s mind.”

A chapter of “The Revolution Starts at Home” (the zine) called “taking risks: implementing grassroots community accountability strategies” provides another example. The authors, a collective of women of color from Communities Against Rape and Abuse (CARA)—Alisa Bierria, Onion Carrillo, Eboni Colbert, Xandra Ibarra, Theryn Kigvamasud’Vashti and Shale Maulanaauthor—describe a series of actions taken by members of an alternative punk community to address sexual assaults by Lou, a man employed by a popular club.

The authors report that Lou “encouraged […] women to get drunk and then forced them to have sex against their will.” In their discussions about what to do, community members “not only reflected on the survivors’ experiences, but also how the local culture supported bad behavior.” For instance, the popular alt-weekly paper often glamorized the massive amount of drinking prevalent at Lou’s parties. With the survivors’ consent, the group designed fliers that identified the man and his behaviors, called for accountability, critiqued the local paper and suggested boycotting the club.

In response, the newspaper published an article defending the man, implying that since the survivors had not filed criminal charges, their allegations were not credible. Lou also threatened to sue them for libel. But the group persisted, working with the survivors to create a document that not only shared their experiences, but also articulated a critical analysis of sexual violence and rape culture in their community and what they meant by community accountability. They released the full statement to the press and posted it to their website, sparking discussions in the larger music community about sexual violence and accountability. Lou stopped being invited to parties and events, locals began boycotting the club and out-of-town bands avoided playing there, prompting Lou to agree to engage with the group and negotiate a face-to-face meeting. Ultimately, however, he never took accountability for his actions.

The group also began a process to learn more about sexual violence, safety and accountability, learning to facilitate their own safety and accountability workshops and supporting CARA and other anti-violence organizations. “It’s a critical shift to decide to use your resources to build the community you want [rather] than expend all of your resources by fighting the problem you want to eliminate,” CARA organizers wrote.

Reflecting recently on that scenario, Bierria, now an organizer with Survived and Punished, noted that “it was a powerful counter-response to something that’s usually not spoken about.”

At the same time, she pointed out, “community accountability is not just a process of accountability. It’s creating conditions within the community that prevent harm.” It can be frustrating, she acknowledged. “We [often] want a more direct solution. But sexual and domestic violence are more complicated than that.” Over the past two decades, she and others working at the intersections of gender violence, community accountability and prison abolition have documented their processes, creating blueprints and road maps that she and other organizers did not have 20 years ago.

These examples show that the processes of community accountability are messy and rarely follow a uniform path. They often, however, mix and match from a distinct set of alternative tools that include actions for both organizations and individuals. Counseling for the person who caused harm, removal from leadership positions, admission of guilt, public and/or private apologies, workshops and trainings, and specific behavioral changes are just some of the demands that communities can make. Regardless of what forms they take, continuing to explore alternatives to state violence in response to gender-based violence is an essential piece of the movements to end both.

[1] INCITE! has since changed its name to INCITE! Women, Gender Non-Conforming, and Trans people of Color Against Violence

Photo via Wechargegenocide.org

Show Comments