In late 2021, after losing a friend to overdose, Miriam Field began distributing syringes, naloxone, glass pipes and other harm reduction supplies to Nashville-area encampments. The early outreach she did was unfocused, without a clear vision of the kind of work she wanted to do.

“I was angry. I was watching all these other people in my life die, and I’ve lost so many friends,” Field told Filter. “I hit the street just randomly yelling out of my window, asking people, ‘Do you need [syringes]?’ It was just ridiculous, but immediately word started spreading.”

One day while she was out distributing naloxone, someone asked her how much she could spare; he sold drugs around the neighborhood, and wanted to distribute the overdose-reversal medication to his customers. Field gave him 200 doses.

In that moment, she realized the potential of collaborating with local sellers as points of contact for distributing harm reduction supplies. Mobile outreach organization Mainline Harm Reduction was up and running by early 2022.

“We are directly around [drug users] the majority of every day—each and every day,” local seller A-Wex* told Filter. “I’ve got to be able to help them.”

A-Wex is able to give his customers sterile syringes because of the steady supply he gets from Field. “Everybody always paints the pictures they want to paint, but only the people who are really here know what’s going on at the end of the day,” he told Filter. “You have to get out here and do some footwork to know the truth.”

“It might not hold up in court, but it definitely is an arrestable offense.”

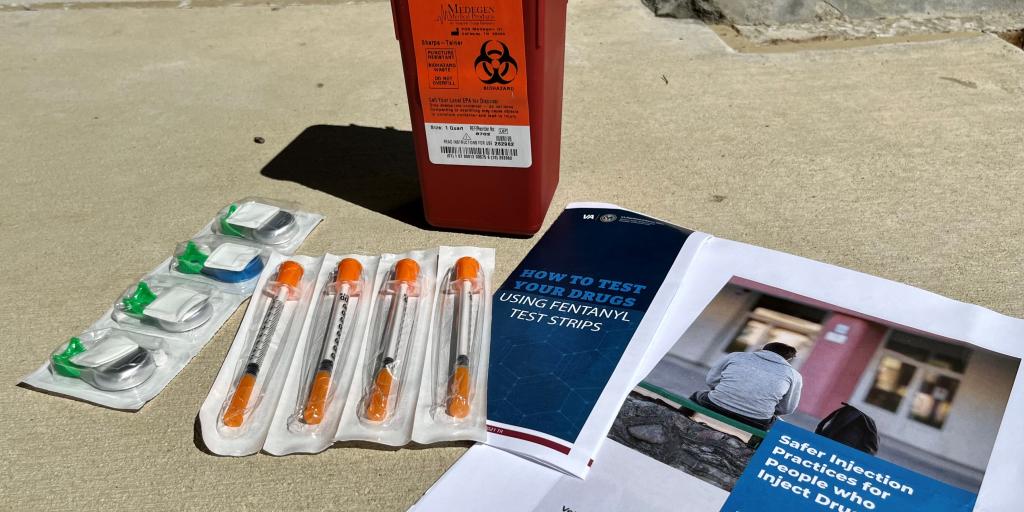

Eleven of Tennessee’s 25 sanctioned syringe service programs (SSP) are mobile sites, but that number doesn’t include unsanctioned entities like Mainline. The sanctioned mobile SSP also differ from Mainline in that they provide services from a fixed location; Field drives around, handing out sterile syringes and other so-called paraphernalia, including glass pipes.

Possession of sterile syringes in Tennessee isn’t illegal in and of itself, but it becomes illegal for anyone who appears to be using them to inject state-banned drugs—unless they’re affiliated with a state-sanctioned SSP.

“It might not hold up in court,” Field said of Mainline’s work, “but it definitely is an arrestable offense.”

Tennessee legalized SSP in 2017, on the condition that programs have to offer treatment services to be eligible for state authorization. State law requires authorized SSP to distribute syringes and other safer injection supplies “in quantities sufficient to ensure that [they are] not shared or reused.” At the same time, it still directs SSP to “strive for one-to-one”—referring to the restrictive policy by which some states limit SSP to only giving sterile syringes to participants who bring in an equal number of used ones. The specter of illegality around needs-based distribution can pressure some programs to not stray too far from one-to-one.

Though sanctioned SSP aren’t permitted to use federal funding to pay for syringes or any other “drug paraphernalia,” many are able to do so using state- or county-level funds. Unsanctioned groups around the state are on their own. In the year and a half since she began Mainline, Field estimates she’s sunk around $15,000 of her own funds into keeping the program running.

“[We’re] barely scraping by in order to do genuine harm reduction, on the level that it really needs to be done.”

“[Fentanyl] is fucking up the economic side of things, because if that’s what it is I don’t bother with it.”

The most common reason sellers approach Mainline is drug-checking, which Field facilitates by sending samples for forensic analysis via a mail-in program.

One of the first people to partner with Field was Q*, who sells cocaine and wanted to check their supply for fentanyl before it reached any customers. Though wary of Field’s intentions at first, Q told Filter, they soon came to appreciate the insight into their supply.

“The last three months [fentanyl in the coke supply has] been constant, it’s been every time,” Q said. “It’s fucking up the economical side of things, because if that’s what it is, I don’t bother with it.”

When opportunity presents itself, Q shares the information with other local sellers as well.

Fentanyl test strips (FTS) are more accessible than forensic lab equipment, and useful for stimulant supplies in particular. Possession of drug-checking equipment is illegal under the state’s “drug paraphernalia” statute, but Tennessee exempted FTS in 2022—except when they’re being used for the purpose of manufacturing, delivering or selling state-banned drugs.

The crux of the issue is lack of a safe supply. It’s also the wave of drug-induced homicide laws spreading across the country.

“Ross was just this incredibly beautiful, vibrant, amazing person,” Field said of the friend whose death pushed her to create Mainline. “And at his funeral, everyone was saying, ‘Oh, he lost his battle with addiction. [But] that’s just not what a drug overdose is.”

Field says the crux of the issue is that people lack access to a safe supply. It’s also the wave of drug-induced homicide (DIH) laws spreading state by state across the country.

“[Anyone] who picks up and shares with a friend, not just kingpin drug dealers, might be the target of these particular laws,” Field said.

In 2018, Tennessee added fentanyl and carfentanil to its long-standing DIH law. This cleared the way for prosecutors to charge sellers with second-degree murder if they were linked to a fentanyl-involved overdose death, regardless of whether or not they knew fentanyl was in their supply.

As of July 1, the state’s “One Pill Can Kill Act,” has broadened the law to apply to all fentanyl analogues.

“Somebody could have ended up in prison for [Ross’ death], and I think that’s an incredible shame,” Field said. “Who gave him what, where he got it from … none of that actually matters.”

*Names have been changed

Photograph via United States Department of Veterans Affairs

Show Comments