In 2016, the Tennessee Department of Corrections (TDOC) opened Trousdale Turner Correctional Center—the largest of the state’s 14 prisons, and the site of constant violence from almost its very first day.

Around that same time, Tennessee’s South Central Correctional Facility decided to try taking the 128 prisoners whose disciplinary records showed the least history of violence, and moving us all into the same living unit.

Over the past several years, while no one was really watching, the residents of Gemini Unit have built community in a way that’s rarely in found in prison. In three decades of incarceration at nine different facilities, I had never experienced a prison environment with a culture of nonviolence sufficient to make anyone safer, let alone one that actively protected LGBTQ prisoners, until I came here.

Now, we’re watching the community we’ve built be taken apart, one person at a time.

Since the beginning of March, by our count at least nine men from this unit have been transferred to Trousdale. All over age 50 with clean disciplinary records. All serving long sentences; most serving life sentences.

“They’ve put me in a hellhole,” one former neighbor wrote to us after he was shipped to Trousdale in late March. “If you are minimum restrict, with no writeups, you may get transferred.”

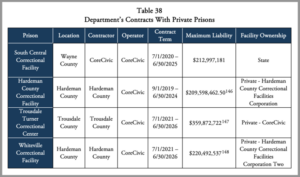

Trousdale and South Central are two of the four Tennessee prisons operated by private contractor CoreCivic. Because the state is only allowed to have one privately operated prison at a time, South Central is the only state-owned facility that contracts with CoreCivic directly. TDOC allows CoreCivic to operate the other three by contracting with the local counties, so that the counties can then contract with CoreCivic.

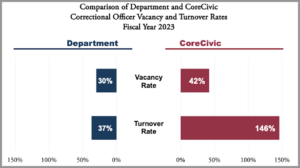

Trousdale is about twice the size of Tennessee’s other CoreCivic-operated facilities, and so is its contract. A state audit showed that in 2023, more than half the correction officer (CO) posts at Trousdale were vacant. The facility’s CO turnover rate was 188 percent, the highest of all 14 prisons. (Among the 10 state-run prisons, the highest turnover rate was 60 percent.)

When a prison doesn’t have enough COs to run it, violence can become the norm quickly. Without security staff, gangs take control of day-to-day operations. Without jobs or programs to pass the time, prisoners become more anxious and angry.

The residential drug treatment program at South Central, for example, has a capacity of 128 prisoners, and as of June 2023 had another 114 on the waitlist. At Trousdale, that program only has room for 52 prisoners, and there are 532 on the waitlist. Its 25-person Cognitive Behavioral Intervention Program, meanwhile, had 1,482 on the waitlist.

One man who was transferred in March wrote to his former cellie here that the bus driver told him he was on his way to Trousdale for “population management.” After three days in an orientation pod, he was assigned to “any open bed on the compound,” and robbed of his belongings before he even got there.

He wrote that since he has no resources or protection at Trousdale, he may soon have “to check in”—declare himself at risk of suicide so that staff will move him to an isolation cell for mental health observation. A miserable experience, but often the only form of protective custody available to those in physical danger, especially for those at the bottom of the prison pecking order.

“Population management” refers to administration moving us around like livestock according to whatever boxes we check on paper. People who fall into some shared category of paperwork get transferred because the facility has too many of you, or another facility needs more of you.

The practice is familiar, but never before has it been this unsettling. Often these kinds of transfers are voluntary—a different prison is starting some new program that you’re a fit for, so they’ll try to incentivize you to sign up—but either way administration normally gives you a reason.

There is no program in need of participants this time. No job vacancies that need to be filled. No explanation from either CoreCivic or TDOC why we’re being rounded up one by one in the night and taken away. Neither responded to Filter’s requests for comment.

“I didn’t get any sleep last night,” one Gemini Unit resident told Filter in early April, the morning after several people were transferred. “Every time I heard a noise, I got up to see if a buggy was rolling in.”

It’s customary to learn you’re being transferred when a CO knocks on your cell door at 3 am. They want you to go quietly, before you’ve had the chance to make any phone calls or cause a scene. We understand that from a security perspective.

But now that we suspect what’s coming, coupled with the silence from administration and the fact that the selections have seemed almost random, the practice is terrifying. It feels like we’re in The Hunger Games, waiting for our name to be drawn in a lottery. We joke a little about needing someone to volunteer as tribute.

The mood here in Gemini Unit is extremely gloomy. This unit is filled with old men who live quietly. How we will survive if transferred to Trousdale, we don’t know.

Broadly speaking, Gemini Unit residents are old men without gang affiliations who live quietly quietly. Presumably we’re being transferred in an attempt to dilute the violence concentrated at Trousdale. Our reward for spending the past few decades working hard and staying out trouble, in the hope of avoiding this kind of situation.

“I’ve done everything this place asked of me,” Suggs, 69, told Filter. “I go to work, mind my business and comply with their rules. It means nothing. I’m just a [dollar amount] that can be moved wherever they want. It’s a hopeless feeling.”

One of the men transferred had begun reconnecting with his family. His mother had just moved to the area so that she could visit regularly in her final years. Now he’s a three-hour drive away.

The mood here in Gemini Unit is extremely gloomy, filled with anxiety and worry. How we will survive if transferred to Trousdale, we don’t know.

“I finally got into a pod where people aren’t killing each other. Finally got a good job,” Heard, 52, told Filter. “I formed a church community and we have service on Wednesdays. The thought of exiting without any chance for closure keeps me up at night.”

I had never experienced a prison environment with a culture of nonviolence sufficient to make anyone safer, let alone one that actively protected LGBTQ prisoners.

Gemini Unit houses the first, and to our knowledge only, openly LGBTQ community in any prison in Tennessee. Be The Change founder Tavaria Merritt began organizing queer and trans prisoners at South Central before many of us were scooped up into the same unit, but physical proximity has helped us find safety in numbers and advocate for our needs in a way that’s almost unheard of during incarceration.

Because nearly half of us here are senior citizens, this unit also houses a mutual aid collective where we work together to provide necessities like denture cream. Many of the older prisoners here who use wheelchairs or walkers, or are otherwise physically ineligible for job placement, also have no family or outside resources. They’re unable to buy items from commissary because they have no access to money. If their neighbors had not organized to care for them, they would be alone.

Putting all the prisoners who aren’t “troublemakers” in the same unit didn’t create that culture in and of itself. It gave us the respite we needed in order to build it. To start our own book club and crochet club when the prison itself offered us no programming, and then to grow them into spaces where we provide each other mental health support, which is also not offered by the prison.

Many people who know they will be in prison for the rest of their lives still avoid referring to it as their “home.” I understand that, and I don’t like that this is the place we have to live either. But it is. Community exists at South Central because people who knew they’d be in prison for the rest of their lives—LGBTQ prisoners, older and disabled prisoners, unaffiliated prisoners without a dollar to their name—had a chance to build it. Many of us did so with the shared hope that this would be our last prison.

We don’t expect administrators to concern themselves with our preferences, or really to see us as more than dollar signs. But separating a community into vulnerable individuals and sending them into a more violent prison won’t make that prison less violent. And by more or less leaving us alone these past few years, they’ve ended up with a microcosm of exactly the kind of rehabilitative environment they say they want. Why not allow it to grow?

Photograph via Pennsylvania Department of Corrections. Inset graphics via Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury.

Show Comments