The federal government has enacted the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Reauthorization Act of 2025, building on the original 2018 version that at the time represented the largest-ever expansion of federal funding for substance use disorder treatment and recovery programs. The Act expired in 2023, and although many programs remained funded in its absence, the reauthorization promises continued funding through 2030. President Donald Trump signed HR 2483 into law December 1.

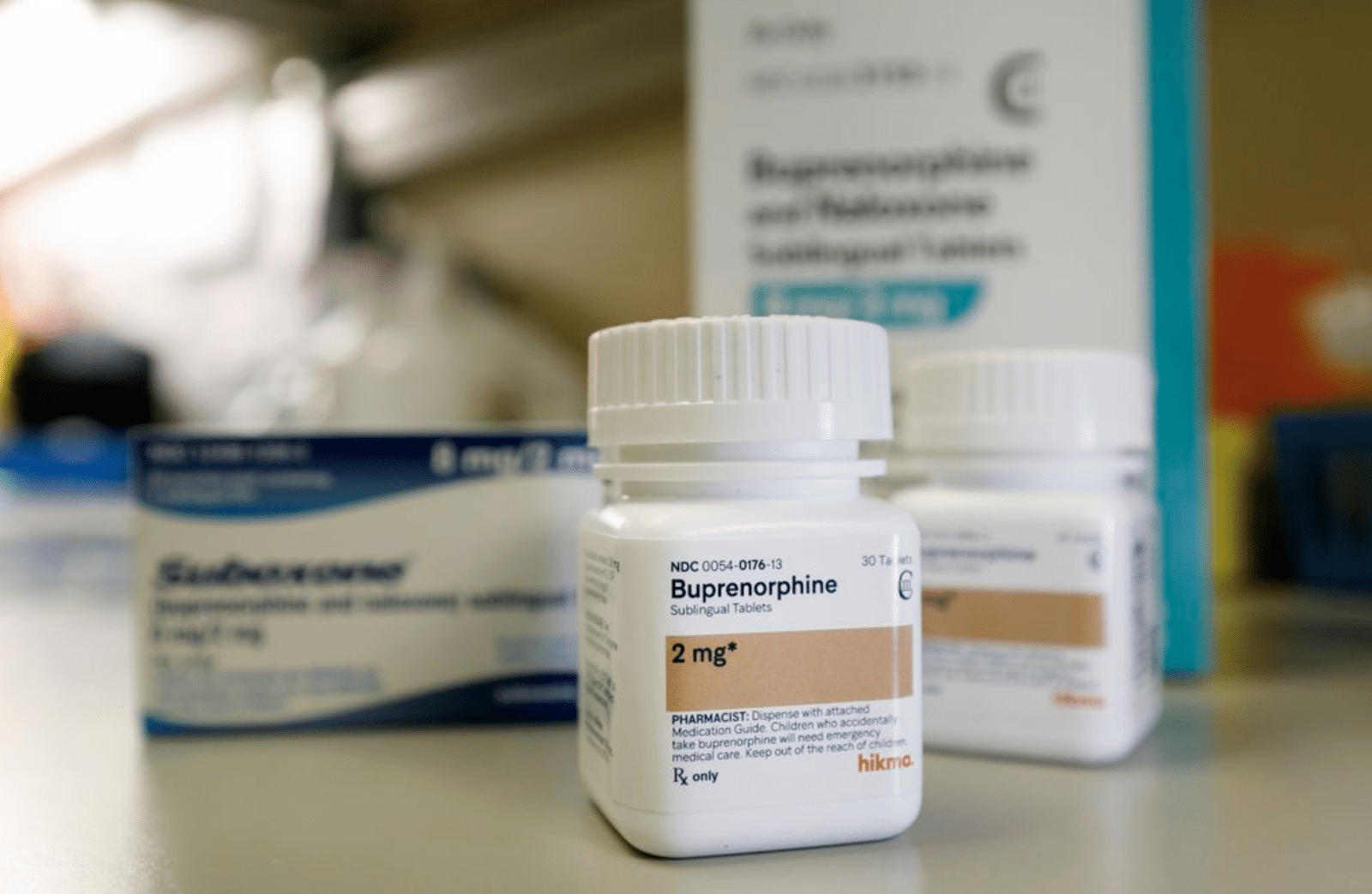

In 2018, the SUPPORT Act established Medicaid coverage for all three medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD)—methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone. But the 251-page document doesn’t acknowledge harm reduction outside of a single paragraph covering syringe service programs, and the 2025 reauthorization doesn’t add anything on the subject.

The original Act commissioned a study focused on access barriers to buprenorphine, naltrexone and “buprenorphine-naloxone combinations” AKA Suboxone. It left out methadone, the MOUD with the most obvious access barriers, but seven years later one of the more notable additions in the new version is a section that advances the potential rescheduling of Suboxone, or any buprenorphine/naloxone combination product.

Naloxone is not a controlled substance. But buprenorphine is, under Schedule III alongside drugs like ketamine and testosterone. The Act directs the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to “review the relevant data pertaining to the scheduling of products containing a combination of buprenorphine and naloxone that have been approved under section 505 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act [and] if appropriate, request that the Attorney General initiate rulemaking proceedings to revise the schedules accordingly with respect to such products.”

This requirement appeared in the reauthorization bill approved by the House Committee on Energy and Commerce in 2023, but neither that bill nor the Senate version was advanced in time to replace the original Act before it expired that September.

The reauthorization quietly advances the campaign to install nalmefene as a viable alternative to naloxone.

Among the other additions that weren’t in the 2018 version is an amendment approved by legislators in June—proposed by Rep. Robert P. Bresnahan (R-PA), whose cousin died of overdose. It prohibits HHS grant guidance from singling out naloxone as the default opioid-overdose reversal medication:

“The Secretary of Health and Human Services shall ensure that, as appropriate, whenever the Department of Health and Human Services issues a regulation or guidance for any grant program addressing opioid misuse and use disorders, any reference to an opioid overdose reversal drug (such as a reference to naloxone) is inclusive of any opioid overdose reversal drug that has been approved … for emergency treatment of a known or suspected opioid overdose.”

Bresnahan, who since taking public office for the first time in January has become best known for ethically dubious stock trades, described this slightly differently in his testimony to colleagues. He stated that current “HHS regulations refer to certain name-brand drugs, such as Narcan, which can limit usage of other versions that may be more readily available.”

This is a really good point, though completely different from the one Bresnahan is intending to make. Using the brand name “Narcan” rather than the generic “naloxone” does contribute to generic injectable naloxone being overlooked by public officials, even though it’s more affordable and in many cases more humane. This is not the problem Bresnahan is looking to solve.

Many overdose-response regulations refer to naloxone as the default opioid-overdose antidote because up until 2023 there weren’t any others. But since Food and Drug Administration approved the first such antidote formulated with nalmefene, a different chemical compound, pharmaceutical companies and other stakeholders have been pushing legislators to cut references to naloxone in favor of “any opioid overdose reversal drug” approved by the FDA. The campaign to install nalmefene as a viable alternative to naloxone has continue despite emphatic warnings from public health experts about nalmefene’s higher risk of overdose and unnecessary suffering for people who regularly use opioids.

Image (cropped) via Drug Enforcement Administration