St. Louis County, the most populous in Missouri, recorded a decrease in overdose deaths in 2022—the largest fall in the past decade. Local officials and overdose prevention workers credit increased distribution of naloxone and better education. But large numbers of people are still dying. And overdose deaths in the city of St. Louis increased.

St. Louis is the biggest city in Missouri. St. Louis County surrounds the city, but is administered separately: It has urban, suburban and rural areas, with 88 municipalities including Ferguson, Wildwood and Chesterfield. The city and county each have their own public health and medical examiners’ offices that count overdose deaths. This may have contributed to confusion over the data in recent months.

On March 30, the University of Missouri-St Louis Addiction Science Team published a report on 2022 overdose data. It showed that overdose deaths decreased dramatically in St Louis County, and also fell in the city. But a few months later, on July 8, local outlet The St. Louis American published different figures, showing that overdose deaths actually increased in the city of St. Louis from 2021-2022.

“We apologize not only for the inconvenience of this update, but the false hope our original report may have offered.”

The university researchers then contacted local health officials for a recount, and ultimately corrected their initial numbers. An email from the Addiction Science Team obtained by Filter stated: “Our original report was based on preliminary data. Unfortunately, upon following up with the local Medical Examiners, we learned the number of cases finalized after the preliminary count was released was much greater than anticipated.”

It continued, “Thank you for your understanding and patience, and we apologize not only for the inconvenience of this update, but the false hope our original report may have offered.”

The revised University of Missouri-St. Louis Addition Science Team report, shared with Filter on August 7, now shows 448 lives lost in St. Louis County in 2022, an 11 percent decrease; but 489 lives were lost in the city of St. Louis an 8 percent increase in the city. St. Louis County has around 1 millon residents, while the city has about 300,000; so these overdose figures reflect a much higher concentration in the city.

Combined, the city and county saw a 2 percent decrease in overdose deaths. These numbers are significantly worse than those reported earlier in the year.

In the city and county combined, overdose deaths have consistently trended up since 2011. They peaked in 2020 at 957—the highest combined total ever recorded—and have declined only slightly since then.

In the city, according to the revised data, Black men remained the demographic group most vulnerable to fatal overdose. The biggest increase in 2022 was among white women.

In the county, meanwhile, white women were the only demographic group for which overdose deaths increased in 2022; the largest decreases were among Black men and women. White men were the most vulnerable demographic listed.

Opioids continued to be involved in the bulk of overdose deaths, at 74 percent of the combined city and county total. Fentanyl was present in 97 percent of opioid-involved deaths. While data attributing deaths to stimulants are notoriously unreliable, 30 percent of all fatalities, according to the figures, involved both opioids and stimulants.

“We have seen continued increase in Narcan distribution, and in requests for Narcan. We believe the cumulative approach of addressing this from all angles is contributing to the county decrease.”

The county’s decrease in overdose deaths, local experts say, is at least partly attributable to harm reduction work by government and private organizations, and to residents being better equipped and informed.

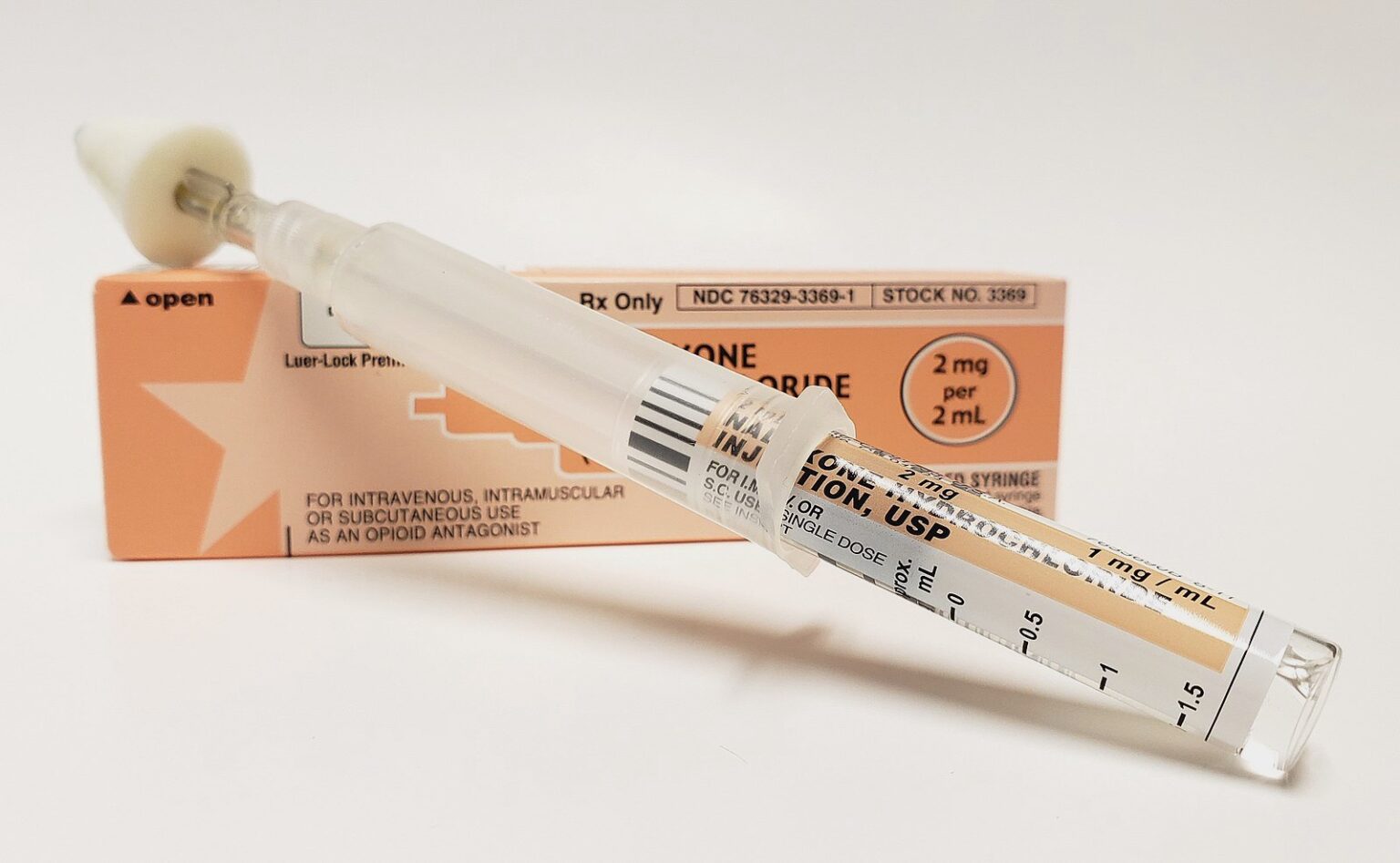

In the Greater St. Louis area, providers like PreventEd are helping to distribute naloxone and fentanyl test strips. PreventEd and the People’s Health Center partnered to install 75 “NaloxBoxes” in public areas around the metro area. Each box contains two doses of Narcan, with instructions in several languages.

“We have seen continued increase in Narcan distribution, and in requests for Narcan,” Jenny Armbruster, PreventEd’s deputy executive director, told Filter. “We know there has been some decrease in overdose deaths. We can’t take all that credit but we believe the cumulative approach of addressing this from all angles is contributing to that decrease.”

“We’ve been doing this work since 2016,” she continued, “and we have seen a reduction in stigma related to people being open to these conversations around opioid overdoses and making sure they have these preventative measures, more people requesting Narcan and establishments being willing to have it [on site].”

“I think we’re having a disparity between some of our populations in the St. Louis metro region, where some areas have access to more resources than others.”

But the improving situation in the county contrasts with that in the city, where, according to the Medical Examiner’s Office, overdose deaths also rose by 30 percent from 2017 to 2021.

“In our city we have ‘resource deserts’,” Armbruster said, “and areas that experience other social determinants of health and lack some of the resources that help support people for both substance use and basic health care, employment and nutrition. I think we’re having a disparity between some of our populations in the St. Louis metro region, where some areas have access to more resources than others.”

Residents of the city of St. Louis residents face numerous connected disparities. The city has a poverty rate almost twice as high as the rest of the state, and almost one in five unhoused people in Missouri live there. The city also jails people at a much higher rate than other parts of Missouri.

Photograph by Intropin via Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons 4.0

Show Comments