A talking point often circulated in harm reduction is that the moment someone is released from incarceration, their risk of dying from opioid-involved overdose goes up by an extremely large percentage. There’s a parallel phenomenon for tobacco-related deaths. Incarceration is associated with precipitously increased cancer risk, lung cancer in particular. Among people who’ve been incarcerated, lung cancer prevalence is tripled.

The number of people diagnosed with lung cancer while in prison is low—but it’s very high among people recently released. Obviously the process of walking from inside the prison gate to the outside is not giving people lung cancer. Prisons keep their lung cancer prevalence numbers low by simply not screening us for it.

The largest proportion of cancer deaths in the United States come from lung cancer, and most lung cancer comes from smoking. Smoking is already the leading cause of preventable death in the US—it’s a major cause of cardiovascular disease, in addition to other types of cancer besides lung—but the situation is much more dire for those of us inside the nation’s prisons. Smoking prevalence here is around six times higher than in the free world.

Since I entered Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) custody 30-plus years ago, the prisoner population over age 50 has multiplied by more than five. Within the next few years, those of us in this older group will comprise more than one-third of all prisoners in the US.

In an informal survey of 100 GDC prisoners, zero had ever been tested for lung cancer while in custody.

In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) updated its guidelines for the populations that it recommends get annual lung cancer screenings via low-dose computed tomography (LDCT). It lowered the minimum age from 55 to 50, and included people who don’t smoke as heavily as in its previous guidance, issued in 2013.

This nearly doubled the number of people who fit the criteria, and was applauded for making access to a lifesaving intervention more equitable among vulnerable populations.

Minus the vulnerable population that’s specifically skewed toward older people who’ve smoked for a long time, of course. That’d be us.

The US mass incarceration crisis is not just due to how many people are being sent to prison, but to how few of us are being let out. About one in seven US prisoners today has been sentenced to half a century or more.

Lung cancer screenings are underutilized in the US no matter where you look, but state prison systems are special. They don’t utilize the screenings at all.

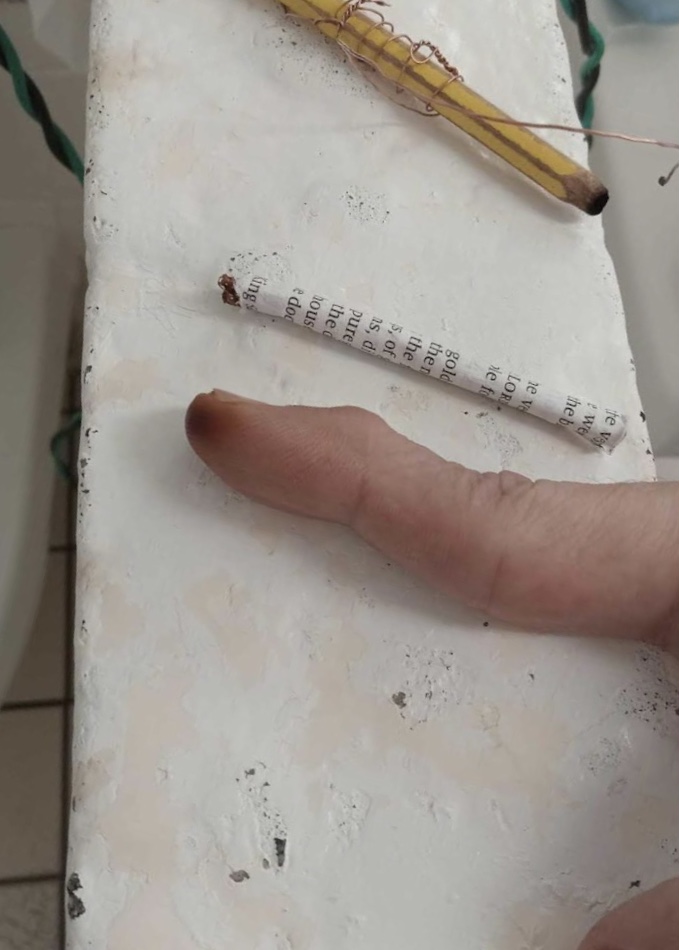

About $2 worth of tobacco

Preventive Care, for Everyone Else

Though USPSTF recommendations aren’t mandated by law, many health care providers follow them because it’s a bad look for them not to. Correctional facilities aren’t among them. GDC is one of many state prison systems to have outsourced our so-called health care to a private contractor, promising ever more creative ways to cut costs.

Of course, in the long term a healthy prisoner population costs less to maintain than a sick one, especially as all of us keep getting older and more disabled. But none of these companies are planning to hang around here as long as we are.

In an informal survey of 100 GDC prisoners reached by Filter during autumn 2023, zero had ever been tested for lung cancer while in custody. Only 15 had been screened for any cancer at all. GDC did not respond to Filter’s request for comment.

As with the previous version of USPSTF lung cancer guidance, the 2021 update was prompted by a very large study. The USPSTF generally aims to update guidance every five years or so, but only if there’s new research to support it.

“It depends a lot on the availability of evidence,” USPSTF member Dr. Michael J. Barry told Filter. “For example, the big reason that we updated the 2013 recommendation … was we were aware, as many people were, that there was this second large trial going on in Europe that addressed the benefit of screening in lighter smokers, and younger smokers. It was really the availability of that second trial that made it important for us to re-address our recommendation.”

Some research on cancer among prisoners will simply leave out lung cancer—there are no guidelines to screen for it.

There is some evidence supporting a link between incarceration and lung cancer risk, just not yet enough of it and no one’s in a hurry to gather more. Despite the captive population of its exact target demographic sitting right here, aging further into the USPSTF criteria by the day, there’s nothing explicitly saying the guidelines apply to us, and no sufficiently fancy trials on the horizon to point out the obvious reasons we need them.

Meanwhile, some research on cancer prevalence in prisons will simply leave out lung cancer because there are no guidelines to screen for it.

In 2022, the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) added the USPSTF recommendations for LDCT scans to its preventive health care clinical guidance. But this is only for federal prisoners, of which there are around 157,000. State prisons hold more than 1 million people. Two years after the USPSTF guidelines were updated, a Connecticut study appears to be the only one suggesting they be applied to state prisoners.

In November, the American Lung Association released its annual “State of Lung Cancer” report and announced that lung cancer survival rates “are improving for everyone.” Which tracks, because once you’re locked up no one remembers to count you for that sort of thing. The ALA did not respond to Filter‘s request for comment.

“The first question is whether there’d be any reason to think the benefit of lung cancer screening would be any different, based on age and smoking history, than people who aren’t incarcerated,” Barry said. “In general, we think these are recommendations for the adult population in the United States. No matter where they live.”

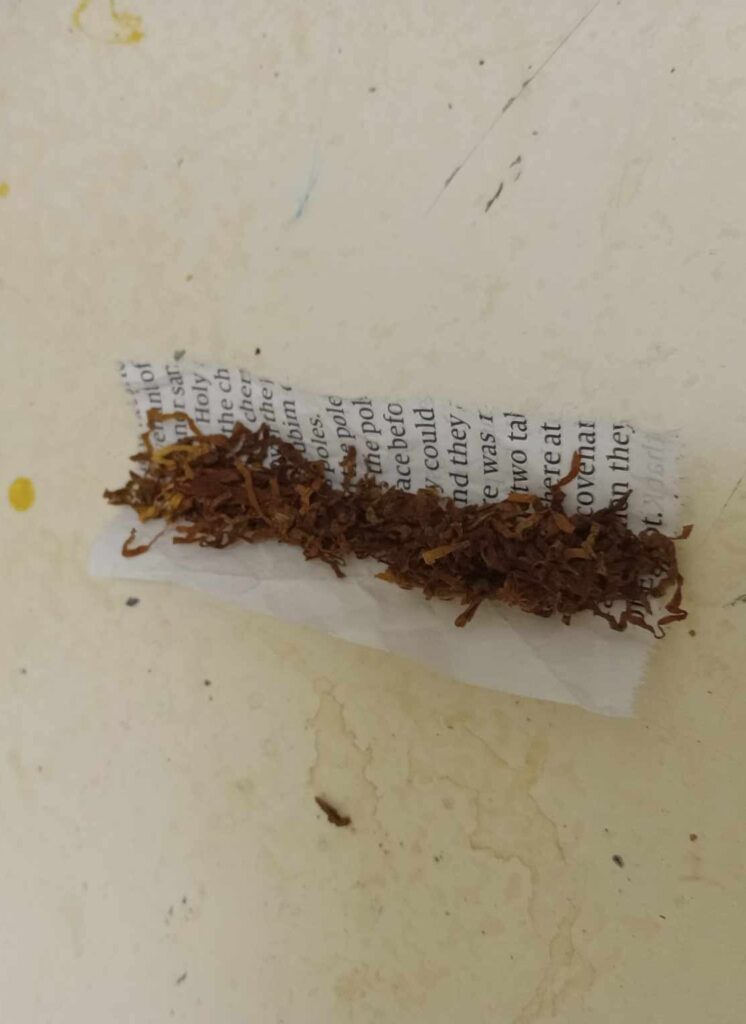

An average filterless cigarette

What a “Successful” Tobacco Ban Looks Like

Like many people across the US, I’ve been in prison long enough to remember when cigarettes were still sold legally at commissary. Since the 1990s, state prison systems have imposed tobacco bans one by one. Some just banned combustible cigarettes, or smoking them indoors. Others banned all forms of tobacco entirely, as the BOP did for federal prisoners in 2014.

Prison tobacco control enthusiasts like to cite the same BOP data showing that since the broad uptake of smoking bans, especially the more restrictive ones, rates of smoking and smoking-related deaths in prison have gone down. They also like to stop before the part about how nearly everyone forced to quit smoking while behind bars is basically lighting up by the time they’re out of the parking lot.

Forced abstinence does stop some prisoners from smoking, or smoking as much, if the thriving contraband market isn’t something they’re able or willing to access. It does nothing to reduce smoking prevalence in the long-term, and appears to actually increase it. Banning cigarettes definitely increased their harm to prisoners overall.

This was the first harm that tobacco bans wrought: All smoking moved indoors.

“When I first entered prison they would ask, ‘Smoking or non-smoking?’” Bill*, who began his GDC sentence 25 years ago, told Filter. “It wasn’t a joke; they issued smokers an ashtray. But sent us to the same cells.”

But the moment cigarettes went under prohibition, smoking became something you had to do in secret like using any other banned drug. That meant it was no longer safe to smoke outside, in plain view of the guards. This was the first harm that tobacco bans wrought: All smoking moved indoors.

Smoking bans started picking up momentum in the ’90s by claiming to protect prisoners just like Bill. In a quarter-century behind bars, he never smoked cigarettes himself. But he was usually housed in a cell with someone who did. By the time staff at Augusta State Medical Prison ran the tests, he was already dying of throat cancer. Smoking is the leading risk factor for that one, too.

“No one can tell me what specifically caused my throat cancer,” Bill said. “One day my throat was sore. It stayed sore.” A few months after we spoke, Bill got the only thing he wanted from GDC and its anti-health health care: to “die naturally, without all the extended warranty crap.”

The last inch of a filterless cigarette

What beyond these walls would be described as secondhand smoke is in here what we simply call “air.”

“All the fumes just lingered in the air when no windows could be opened,” recalled Floyd*, who paroled out four years ago. The HVAC systems barely moved any air because the vents stayed full of either dust or mold, depending on the season.

In his three decades inside what he termed GDC’s “chemical-rich environment,” the only cancer screening Floyd remember being offered was the occasional mention of a prostate exam during the annual check-up. Those came around once “every five years or so.”

In the free world, people might have access—to varying degrees—to cigarette alternatives that reduce or entirely remove cancer risk, including vapes, heated tobacco products and smokeless tobacco products like snus. In states with less restrictive prison tobacco bans, there have been very promising, yet very isolated, attempts to bring vapes into commissaries.

Contraband vapes, meanwhile, are of little to no interest here—unlike bulk tobacco or individual commercial cigarettes, you can’t make any money off them by breaking them down and marking up the smaller quantities.

Like any other banned substance, inside or outside prison, tobacco’s function isn’t just to provide a certain effect. Tobacco is also money. Even if someone was educated about the benefits of vapes and wanted them for personal use, there’s no existing infrastructure to bring them in and doing so involves too much time, money and risk to seem worth it.

. The THR movement is about moving away from commercial cigarettes, but in prison those are the less-harmful alternatives.

Though the tobacco harm reduction movement is focused on moving toward these alternatives and away from combustible cigarettes, we prisoners would gladly take the latter off your hands if they could be sold to us at commissary. In here, commercial cigarettes are the less-harmful alternatives.

In addition to making sure everyone got daily secondhand exposure whether they smoked or not, the bans made cigarettes themselves more harmful. Commercial smokes brought in as contraband were marked up too high for the poorest among us, and so teeny, re-rolled filterless smokes became the norm.

When I first picked up smoking some 40-odd years ago, I was taught to never smoke the last inch of a cigarette, because that’s where the tar accumulated. You consume tar when smoking any part of the cigarette, but people with the luxury of not inhaling every ash will flick the last inch to the ground unfinished. Those less fortunate will go pick it up.

Why would anyone smoke the last inch of a cigarette? Because in prison they can cost up to $100 a pack. Many cigarettes being filterless, it’s a sign of wealth here to smoke and not have fingertips visibly burned from holding one all the way to the end. A sign of poverty: thick, burned calluses like lumps of coal.

Put Cigarettes Back in Commissary

If prison administrators really wanted to stamp out all the contraband tobacco, it would not be complicated to do. You have captive buyers starving themselves to put up three ramen soups—70 cents each at commissary—in exchange for one tiny, filterless cigarette. Put commercial cigarettes back in commissary at $10 a pack, and watch the illicit market wither and die.

If our right to smoke were reinstated, a large majority of prisoners who smoke would happily take their $10 packs outdoors. Wealth (such as it is here) would be less concentrated at the top. With pockets not emptied so quickly, more people purchasing food items at commissary might actually be able to eat them, rather than trade them for cigarettes. Theft of food items would decline. Less hunger, less desperation.

Tobacco harm reduction behind bars is also violence harm reduction. If the Department of Justice—which has been pondering the violence inside GDC facilities for the past two years without much action, at least that we prisoners have been able to see—were really interested in reducing that violence, it should know that cigarettes in commissary at $10 a pack would do that immediately. If GDC saw fit to update its tobacco ban, it could turn an even larger profit by selling us marked-up vapes and other less harmful alternatives, too.

Not all contraband is sold on credit, but tobacco is. For prisoners trapped in poverty, which most are, unpaid debts are a health hazard greater than cancer. Which in the end will come for them anyway. Until then, many will keep burning the candle at both ends, all the way down to their fingernails.

Photographs via Anonymous

*Names have been changed to protect sources.

R Street Institute supported the production of this article through a restricted grant to The Influence Foundation, which operates Filter. Filter‘s Editorial Independence Policy applies.

Show Comments