Nationwide, prisoners and their loved ones are reeling from exorbitant commissary price hikes that are pulling basic food and hygiene staples out of reach. In Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) facilities, where conditions have prompted multiple simultaneous investigations by the Department of Justice, the impact of the increases has been drastic enough that in late 2022, friends and families began petitioning GDC en masse.

In 2022, GDC Ramen soups—the primary prison food staple—rose from $0.39 to $0.48, a 20 percent increase. Hydrocortisone cream rose by nearly 45 percent, Tylenol by more than 33 percent and coffee by more than 15 percent.

Petitions reviewed by Filter asked GDC to meet recent price hikes with corresponding increases in weekly spending caps. Prisoners face spending limits that are determined by factors like their security level and the limits set by state systems, and in some cases by availability of certain products. These caps remain unchanged.

“The sale of bad food to prisoners, besides being unconstitutional, is also an unethical, predatory and extortionate practice.”

“Ramen soup, a pack of cheese crackers and a soda—that allowed a $50-a-month budget to get me through with a few hygiene items. Maybe a box of oatmeal pies a couple of times a month. Or a dollar to spare to feed someone else a meal when the weather was just too miserable to go to the chow hall, or if you just wanted to help someone out,” J.D., 42, incarcerated at Central State Prison, told Filter. “Now, a dollar won’t buy a soda.”

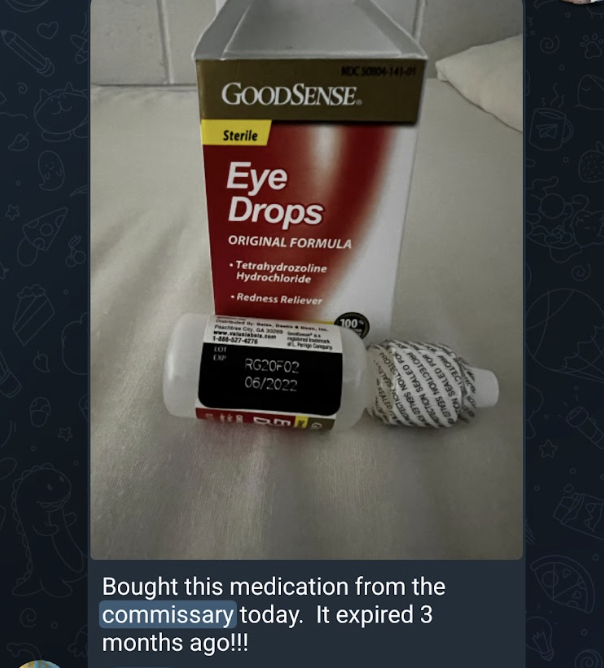

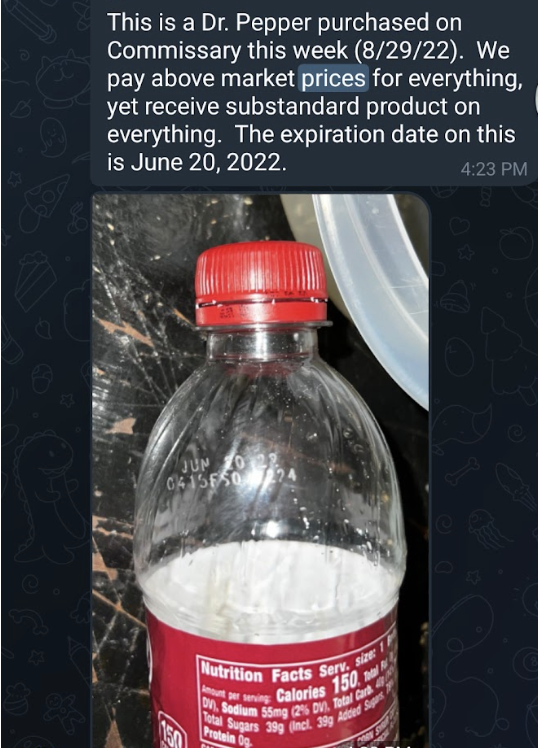

The increased prices are not reflected in the quality of products available. Food, beverages and medications are frequently expired—often not just by days, but by months. The petitions being circulated emphasize that without increased spending limits, it’s nearly impossible for prisoners to stay healthy.

“It’s our position that the sale of bad food to prisoners, besides being unconstitutional, is also an unethical, predatory and extortionate practice by GDC and its commissary vendor, Stewart Candy Company,” Emily Shelton, the founder of prison reform nonprofit Ignite Justice, told Filter.

According to GDC standard operating procedure, state prison prices are set by the Department and “subject to change without advance notice.” Commissary prices at county facilities are set locally.

“I’m now spending $40 a week to buy what $25 used to.”

Though it’s clear that prisoners are not given the means to meet rising prices, it’s not clear whether the private companies contracted to provide commissary items, like long-time GDC vendor Stewart Candy Company, have caps on just how high they can raise those prices. GDC did not respond to Filter’s request for comment. Oklahoma vendor contracts, which Shelton obtained through open records requests, also did not indicate any guidelines or restrictions around price increases.

Prison commissary prices are intended to be lower than commercial retail prices. However, lack of oversight means this is not always the case. In Nevada, a 2022 audit found that the majority of commissary prices had been marked up compared to retail prices—some by 40 percent. In Kentucky, deodorant sticks being sold for $1.98 at local Walmarts now cost $4.52 at prison commissaries.

“At one time, my folks were sending me $25 every week, and that was just enough,” Zombr3x, 28, incarcerated in a Middle Georgia Correctional Complex prison, told Filter. “I’m now spending $40 a week to buy what $25 used to.”

Though it’s standard for commissary prices to go up each year as new annual budgets and vendor contracts are set, in previous years many systems had seen increases of perhaps 2 or 4 percent. Shelton, who collects data on such increases nationwide, said the 2022 increases seem to begin at around 8 percent and go up from there. The Oklahoma private prison where Shelton’s husband is incarcerated proposed a 10.5-percent increase. Since the beginning of the pandemic, systems across the country have seen about a 25-percent increase overall.

Albert, 49, incarcerated at Dooly State Prison, criticized the practice of charging one dollar each month simply for prisoners to keep money on their commissary accounts. Visits to medical staff already come with $5 copays, plus another $5 for any medicine prescribed. This often means relying on commissary for over-the-counter items, or going without them. Even the act of putting $20 on a commissary account costs loved ones a $3.50 fee, for the prisoners fortunate enough to have them.

Commissary purchases are not luxuries. They are the difference between eating and going hungry, between having warm clothes or freezing.

“When you don’t have no one, no family … you gotta fend for yourself,” TearDrop, a 29-year-old trans woman at Valdosta State Prison who relies on sex work to survive, told Filter. “In here store [goods] is your coin, your currency … it’s definitely more now [and] a girl’s gotta eat.”

Commissary purchases are not luxuries. They are the difference between eating and going hungry, between having warm clothes or freezing through the winter. The price hikes mean fewer and fewer prisoners are able to buy toothpaste, or Tylenol, or denture cream, or underwear. This is true of prison systems nationwide, but it is excruciating for those impacted by a system so gravely overcrowded and underfunded as GDC, where prisoners are sleeping outside and the understaffing crisis has left prisoners and their families pleading for administrators to call in the National Guard, to no avail.

“Everyone in here is still a legal slave paid not even a single cent, and folks on the streets rightfully have to look after their own bills,” 57-year-old GDC prisoner Jimmy told Filter. “Maybe that’s why these states have the most trouble; hungry prisoners cannot be expected to behave.”

Top photograph via Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Inset screenshots of GDC prisoner backchannel platforms via Anonymous.

Show Comments