Tensions and frustrations building for years have spilled into Massachusetts’ cannabis regulatory meetings in the past few weeks. Advocates have staged protests at the Cannabis Control Commission (CCC) meetings where the five-member panel awards business licenses.

Twice, on December 19 and January 9, advocates have interrupted the public meetings to ask why, since Massachusetts’ cannabis equity program began, no applicants to the Economic Empowerment program have yet received final business licenses. It has been four years since the state legalized, and two years since legal sales began.

The demonstrations involved chants and speeches, and resulted in the CCC prematurely adjourning both meetings.

Cannabis equity in Massachusetts comprises an Economic Empowerment Program, focused on priority in licensing; and a Social Equity Program, focused on training and education, on which Filter previously reported.

Applicants were eligible for the Economic Empowerment program if they could “demonstrate experience in—or business practices that promote—economic empowerment in communities disproportionately impacted by high rates of arrest and incarceration for offenses under state and federal laws.” Applicants were due to be given priority in the CCC’s license application review process.

Economic Empowerment applicant Leah Daniels asked the CCC on December 19 why she had waited 610 days to hear a response on her application. She claimed she had spent $375,000 renting an unused business location.

“The way the CCC has handled—or lack of handling—this matter, has violated my due process and caused grave detriment to the future of my company’s earning potential,” she said. “The lack of priority review has hindered my ability to participate in the nearly $400 million opportunity of revenue generated in this industry.”

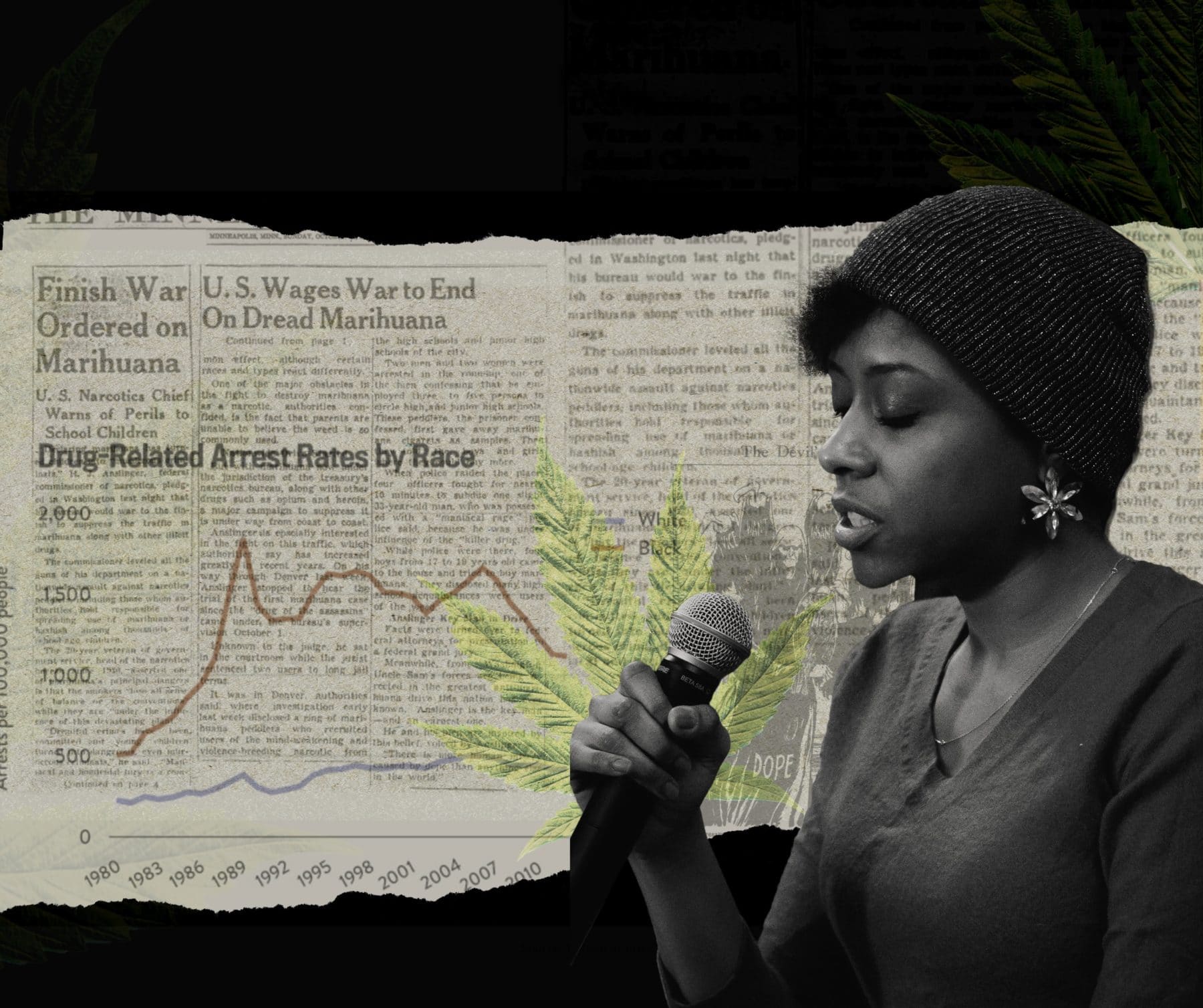

“If we look at the racial wealth gap and the effects of the War on Drugs, this program is not serving those communities.”

“The question is, where is the priority?” Saskia Vann James, a lobbyist with the Massachusetts Recreational Consumer Council (MRCC), asked Filter. “The state is ignoring the equity that needs to be provided. There’s a failure of achievement in the CCC’s mission, and there needs to be accountability for that.”

There are currently 122 Economic Empowerment applicants, of whom 22 have completed their applications. Five of those applicants have received provisional licenses—the last step before a business receives a final license to open its doors. So far, none of the applicants have successfully opened a cannabis business in Massachusetts.

For comparison, there are 367 general applicants with complete applications waiting to receive a provisional license, and 232 applicants from medical marijuana companies looking to open a recreational businesses or “registered marijuana dispensaries” (RMD). To date, 79 cannabis companies have “commenced operations” in the state.

Vann James said that the biggest barrier faced by cannabis applicants in Massachusetts is raising the start-up money needed. “If it takes over $2 million to open a dispensary, but we look at the racial wealth gap in Massachusetts and the effects of the War on Drugs, this program is not serving those communities.”

In an effort to alleviate this problem, MRCC helped propose “An Act to Ensure Full Participation in the Marijuana Industry” (S.1123) in the Massachusetts state legislature last year. The bill would create a fund to give financial assistance to cannabis equity applicants. It would be funded both by the license application fees the state collects and by donations.

Vann James explained that in order to receive a license in Massachusetts, businesses have to create a positive impact plan to benefit their communities. For a company with significant financial resources, donating to a cannabis equity fund could help meet that requirement.

The CCC is only responsible for one step of the licensing process for businesses in Massachusetts. Besides getting your license approved by the commission, you also need to sign a host community agreement (HCA) with your city or town government, and pass many other hurdles, like city and state inspections, before you can open for business.

“Something can be favorable to equity applicants, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy.”

Kobie Evans of Pure Oasis, the first business in Boston to receive a provisional license, explained this to Filter. His company is now working towards its final license.

“There’s a lot that’s outside of our control,” Evans said. “If you don’t have the experience or the money to hire consultants to do this for you, it’s a baptism by fire. The CCC has been the easier part of the process to manage, but dealing with municipal governments has been much hairier if you’re not politically connected.”

Evans spoke positively of how the CCC has conducted the state licensing process. But he noted that reforms like S.1123, funding businesses with loans or grants, would go further in building an inclusive industry.

“You either have the money to do it or you don’t, and it’s very hard without,” he said. “People also need more guidance and technical assistance. There is a misconception about how this process would unfold—something can be favorable to equity applicants, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy.”

Massachusetts has much work to do in meeting its goal of helping people most harmed by marijuana prohibition into the industry. Groups like MRCC are continuing to lobby for legislative reforms, and raising questions about removing regulations that make operating cannabis businesses more expensive.

“We need to make sure this industry is inclusive,” Vann James said. “Cannabis is very giving and there’s enough of it to go around, but that’s not the way the system is set up now. The state needs these businesses’ tax money, and they want to be able to give it.”

Photo of Saskia Vann James by Sarah Hinzman courtesy of MRCC.

Show Comments