The American Bicentennial was a very prolific time in my life. I had just completed fifth grade, and would be a big-shot sixth-grader come September. That first morning of summer vacation 1976, I woke up with anticipation coursing through me. It was going to be an epic summer; I was certain of it.

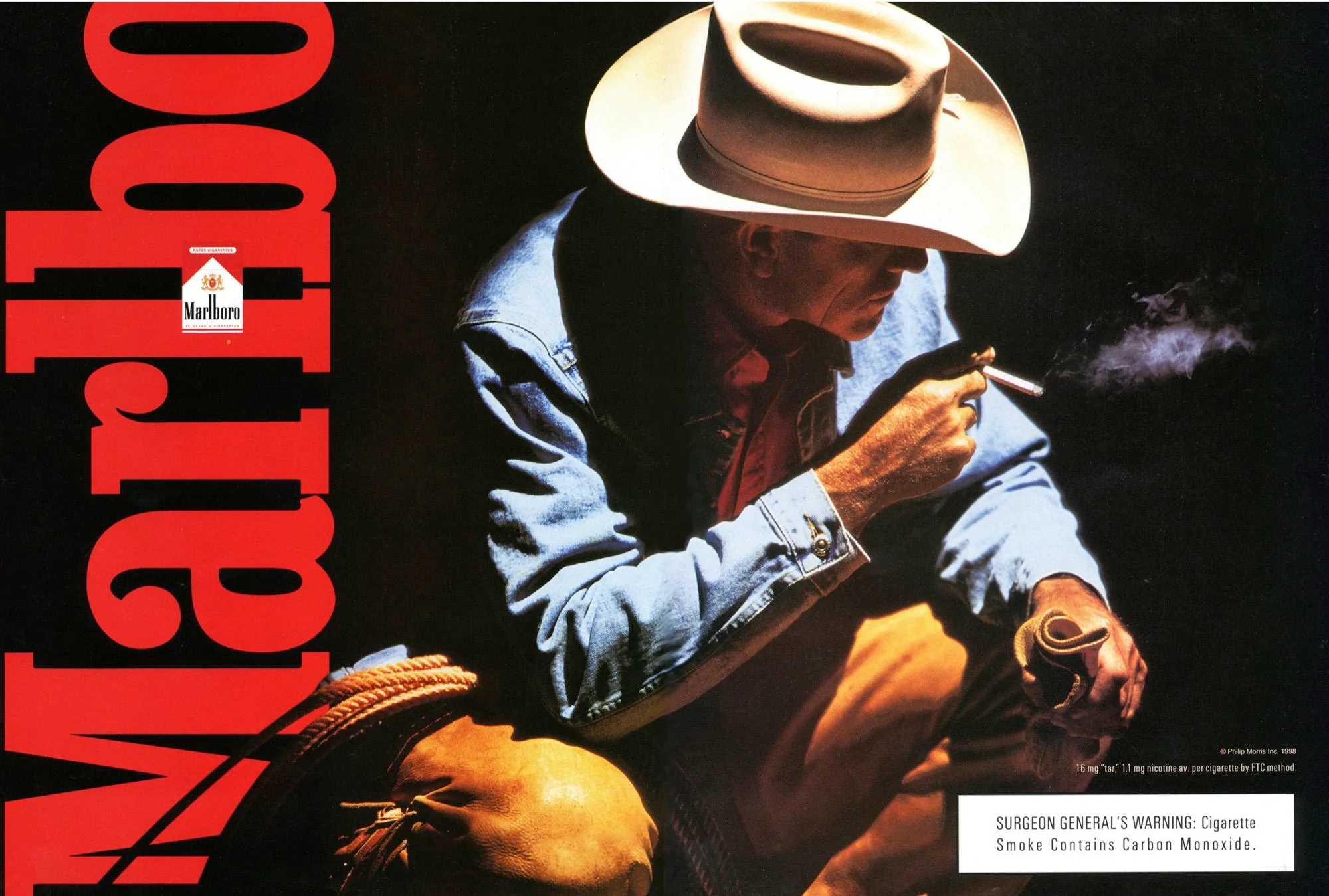

CBS had been playing thought-provoking snippets about the nation’s 200th birthday during commercial breaks. Glued to our 24-inch RCA color TV, my family watched hundreds of these, along with the commercials sandwiched between them. This was how I discovered who I wanted to be when I grew up: the Marlboro Man.

This was a time when TV Westerns were still popular, and quite formative for a 12-year-old such as myself. Smoking could have had no better ambassador than the Marlboro Man, riding off into the sunset on his mustang.

My best friend and I had 26-inch Huffy bicycles with banana seats, and our “horses” meant the world to us. We rode them to every remote corner of our Wild West suburban town, traversing treacherous paths like the rickety railroad bridge or the city dump.

During one such excursion, my buddy came to a sudden halt. He dismounted and picked up a red-and-white box of Marlboros from the side of the road. It wasn’t empty.

There, on the sandy hillside, we each lit our first-ever cigarette.

A mix of excitement and fear rose up within me as we beheld our contraband. We turned and charged off to the rock quarry, to get a better look at the pack’s contents far away from the prying eyes of the law, or our parents.

There, on the sandy hillside, we each lit our first-ever cigarette. We sat mostly in silence, except for all the coughing. We were radiating with the buzz of nicotine and doing something mischievous. With that first cigarette in my hand, I felt teleported into adulthood. I had arrived somewhere I never wanted to leave.

I thought of Becky, who’d sat next to me all through the fifth grade. Surely, if she could see me at that moment, there would be no doubt in her mind that I’d become the coolest kid in school. That thought stayed with me for years.

By the end of that first pack we had mostly learned how to inhale without coughing our lungs out. Now, we rode around town with a new mission. We surveyed roads and ditches, stopping to check each discarded cigarette box before riding on.

We were experiencing our first nicotine cravings, and those had to be dealt with. But we were also hunting for treasure.

We were experiencing our first nicotine cravings, and those had to be dealt with. But we also enjoyed hunting for treasure. Occasionally we’d find unsmoked cigarettes, but for the most part we saved the money from our paper routes and allowances and bought packs from the vending machine at the bowling alley. We figured by the end of summer vacation, we should try each of the different brands at least once.

We kept that first red-and-white box and would fill it with discarded cigarette butts whenever we came across them. Then later, at the rock quarry or in the woods behind the elementary school, we’d remove the filters and clumsily re-roll what remained, the way we’d seen older kids do.

The Huffys carried us faithfully for several more years, until finally they were traded in for a 1969 Ford Mustang Fastback. Becky was often in the passenger seat, and soon she took up the Marlboros too.

Years later when I learned of her lung cancer, I felt guilt for introducing her to the habit; I still do. After decades of smoking cigarettes without knowing less-harmful alternatives existed, let alone having access to them, I avoided serious harms of my own through blind luck, I suppose. Eventually I gave them up. But at 16, cigarettes held nothing but promise.

One night, I was driving with my right hand on Becky’s knee and the sun going down in front of us. My left hand was holding a lit Marlboro, perched on top of the steering wheel. As we rode over a hill and off into the sunset, it felt like life couldn’t get any better. Life was just what my 12-year-old self had dreamed it would be.

Image via Clallam County, Washington State

The Influence Foundation, which operates Filter, has received grants from Altria, the parent company of Marlboro manufacturer Philip Morris USA. Filter‘s Editorial Independence Policy applies.

Show Comments