A new report reveals damning metrics on the global drug war. Despite widespread prohibition, international levels of banned drug use are rising. And by multiple measures—incarceration, access to treatment and drug-related deaths—things are getting worse, year on year, as the drug war drags on. The authors urge governments around the world to change course before more lives are ruined.

The report, compiled by researchers at the International Drug Policy Consortium (IDPC), specifically looks at the global community’s progress on the 2019 “Ministerial Declaration” on drugs, from the 62nd Commission on Narcotic Drugs, held in Vienna by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). That declaration set goals for countries to meet by 2029.

“This report shows that by 2023 there has been little, incomplete or no progress in achieving these goals,” the authors write, noting failures to reduce illicit markets and associated violence and insecurity. Instead, the global drug war impedes UN goals for human rights, health and sustainable development.

“We are at the halfway mark of the current 10-year global drug strategy, yet there has been no effort by governments to conduct a serious evaluation.”

The 2019 declaration stated that countries would continue to follow the 1961, 1971 and 1988 anti-drug treaties or “conventions,” which require member states to ban and control certain drugs. It called these conventions the “cornerstone of the international drug control system,” and urged countries to ratify them if they haven’t already.

“We further reaffirm our determination to address and counter the world drug problem,” it stated, “and to actively promote a society free of drug abuse in order to help ensure that all people can live in health, dignity and peace, with security and prosperity, and reaffirm our determination to address public health, safety and social problems resulting from drug abuse.”

But according to the IDPC researchers, out of 11 different “challenges” identified in 2019, only one has seen “progress made”—for all the others, the world is “off track.”

“We are at the halfway mark of the current 10-year global drug strategy, yet there has been no effort by governments to conduct a serious evaluation,” said Ann Fordham, executive director of IDPC, in a press statement shared with Filter. “When governments convene at the UN in March 2024, they are likely to once again rubber stamp a continuation of the catastrophic ‘war on drugs’ that nobody believes will succeed.”

Even if the 2029 goals were met, the IDPC report emphasizes, they are misguided targets.

There has been “progress made” on allowing more people to get involved in changing their governments’ drug policies, according to the IDPC.

But there has been little or no progress on the 2019 declaration’s goals of reducing the illicit drug market; stopping organized crime; stopping digital technology used in drug sales; protecting the health of people who use drugs; improving access to lifesaving medicine; improving human rights; freeing drug users from prison; resolving potential contradictions between global anti-drug treaties and individual countries that choose to legalize; ending poverty for people involved in the illicit drug economy; or gathering better data on all this.

Even if the 2029 goals were met, the IDPC report emphasizes, several of them are misguided targets. The declaration has “blind spots,” the authors write, on areas that are vital to achieving drug peace. These include legalizing drugs to end problems related to unregulated markets; preventing the use of “surveillance technology”; protecting harm reduction services; prioritizing racial equity and social justice, including the rights of Indigenous peoples; and protecting the environment from damage caused by drug policy.

The IDPC report contains statistics that underline the failures by the 2019 declaration’s metrics.

Over four years, the estimated number of people using banned drugs worldwide has increased to 296 million, a historic high.

An estimated 494,000 people worldwide died of overdose in 2019 alone (including 70,000 in the United States—a number that has since continued to soar).

Executions for drug convictions more than tripled between 2019-2022, while an additional 2 million people were locked up for drugs between 2018-2023.

And worldwide, just one in every five people with substance use disorder can access treatment.

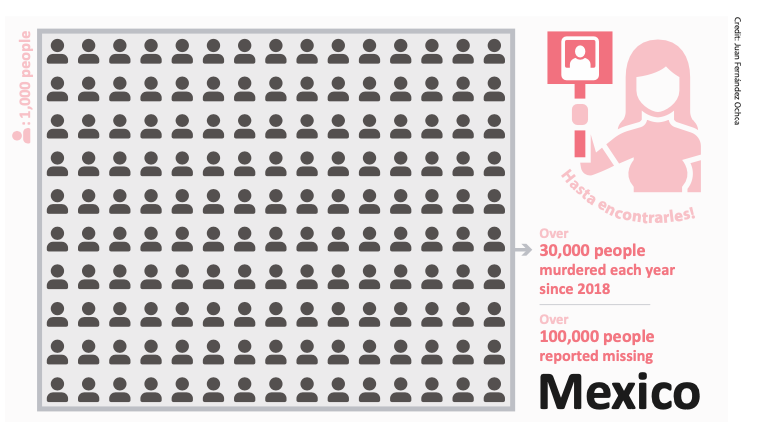

IDPC reports that the global illicit market fostered by prohibition continues to fuel violence and conflict, especially in poorer countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa and Asia, where drugs are produced or transported.

It cites the example of Mexico, which suffered a 2022 homicide rate over 62 percent higher than in 2015. In Colombia, the researchers note that government efforts to encourage coca growers to switch to other crops have resulted in violent reprisals against local leaders.

Violence linked to the drug trade—perpetrated by organized trafficking groups, soldiers, police and paramilitaries—is a major factor contributing to insecurity in Central American countries like Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador, in turn contributing to a crisis of refugees attempting to flee to Mexico and the US.

Violence linked to the drug trade—perpetrated by organized trafficking groups, soldiers, police and paramilitaries—is a major factor contributing to insecurity in Central American countries like Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador, in turn contributing to a crisis of refugees attempting to flee to Mexico and the US.

Drug-war violence is heavily perpetrated by governments, of course. Perhaps the cruelest example in the modern era is the Philippines, which saw a brutal campaign of detention, raids and extrajudicial killings carried out under former President Rodrigo Duterte—who is now being investigated by the International Criminal Court, despite the obstructions of his successor, President Marcos Jr.

But there’s less attention on the fact that at least six countries are believed to have carried out executions for drug convictions in 2022, while hundreds of new death sentences for drugs were handed down the same year.

Over 294 million people worldwide can legally access cannabis for non-medical use—double the figure five years ago.

The IDPC report also points to some hopeful signs. Since 2019, legalization of drugs like cannabis has spread rapidly, including in North America, Europe and Asia. Now, over 294 million people worldwide can legally access the drug for non-medical use—double the figure five years ago. Since 2019, 17 countries have passed laws allowing cannabis for medical use, while six have chosen to decriminalize either all or some drugs for personal use.

And this year, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights issued a call for decriminalizing drugs as a safety and security measure, and “shifting away from punitive models” of drug control.

How to Start Undoing the Damage

In 2024, on March 14-15 in Vienna, the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs will conduct a “midterm review” to assess for itself progress on the 2019 declaration’s goals.

The IDPC authors wrap up with their own set of recommendations. They urge UN bodies including the Office of Drugs and Crime and the International Narcotics Control Board to ditch the unattainable and harmful goal of eradicating drugs, and instead prioritize “protection of health, human rights, equality and non-discrimination.” Member countries should be encouraged, they write, to acknowledge the existence of laws legalizing and regulating drugs like marijuana or coca, and the UN should monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of these laws.

“This report should lay the ground for a process of deep reform that sheds the global punitive paradigm.”

The report also makes longer-term recommendations for moving towards a post-drug war future: Countries, their residents, researchers and UN officials would work together to amend UN anti-drug conventions. An amendment would focus first on health and human rights, and allow countries to pursue legalization and repeal bans on traditional use of psychoactive plants. Bodies like the World Health Organization, it suggests, could write a blueprint for how to legalize drugs in a safe and just manner.

“Throughout my career as a lawyer, judge, and minister, I have seen first-hand how drug laws have driven violence and mass incarceration,” said Diego García Sayán, Peru’s former minister of justice and minister of foreign affairs, in a statement shared with Filter. “This report should lay the ground for a process of deep reform that sheds the global punitive paradigm and protects the health, welfare, and human rights of people everywhere.”

Top photograph of a former Gendarmarie unit in Mexico’s federal police by the Office of the President of Mexico via Flickr/Creative Commons 2.0. Inset images via the IDPC report.

Show Comments