On July 26, Matthew Holman, the director of the Office of Science at the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Tobacco Products (CTP), told staff that he would be leaving his role for an undisclosed position at Philip Morris International (PMI).

Brian King, who became CTP’s director in early July, wrote in a letter to colleagues that Holman would be departing “effective immediately,” revealing that the former OS head “has been on leave since before my tenure began at the Center” and saying that “he recused himself, consistent with agency ethics policies, from all CTP/FDA work while exploring career opportunities outside of government.”

“FDA thanks Dr. Holman for his federal service and wishes him well,” an agency spokesperson said in a statement to Filter. “The work of the Center for Tobacco Products’ Office of Science is essential to our mission to protect Americans from tobacco-related disease and death. We are confident in the expertise and ability of our staff to continue this critical public health work while the Center for Tobacco Products conducts a nationwide search to identify the next Director for the Office of Science.”

King added in his internal memo that Dr. Benjamin Apelberg and Dr. Todd Cecil, two OS higher-ups, would serve as acting OS directors on a rotating basis until a permanent leader is found. (Cecil will go first.)

The announcement caught much of the tobacco control world and industry by surprise, and conjecture surged about the specifics of Holman’s new role and when conversations between him and PMI started. A PMI spokesperson said that details about Holman’s job responsibilities would be shared at a later date.

“Dr. Holman is not leaving the FDA, he’s escaping.”

The timing, though, appeared serendipitous, as CTP—already a frequently maligned entity within tobacco harm reduction circles—has seemed to be running harder and harder into walls. Earlier this month, Robert Califf, the FDA commissioner, said that he was commissioning external experts to evaluate CTP, not long after the agency essentially walked back its denial of Juul’s marketing order and faced endless pleas from legislators to regulate synthetic nicotine, which only recently came under its regulatory authority.

Continuing its piecemeal attempt to institute a “comprehensive” tobacco plan for the future, the FDA is also now weighing a ban on combustible menthol cigarettes and furthering plans to lower the nicotine levels in cigarettes to essentially zero.

“Dr. Holman is not leaving the FDA, he’s escaping,” Amanda Wheeler, the president of American Vapor Manufacturers and a vape shop owner in Arizona, told Filter. “It is hard to avoid the sense that the most serious and essential work on tobacco harm reduction is being done outside of an agency that appears beyond repair.”

As accusations of quid pro quo and “revolving door” behavior began to circulate online, a source with inside knowledge of the development told Filter that talks with Holman, a well-liked and respected scientist, initiated talks with PMI at the beginning of July—and after he had recused himself from his FDA duties.

At least one journalist noted that Holman had signed off on one of PMI’s modified risk tobacco product application (MRTPA) for its IQOS heated tobacco product in March 2022. (The agency had granted the original MRTPA to PMI for its IQOS product in mid-2020, and issued this updated MRTPA to a revised device this past March.) It’s worth noting, though, that the MRTPA did not grant PMI a “risk modification order,” which would have permitted the company to make marketing claims that the product reduces risk of, say, certain disease, and instead received an “exposure modification” order, which allows only a handful of authorized exposure claims.

In a space riddled with bureaucracy, these distinctions are meaningful. It’s easy to draw comparisons to the departed FDA director who approved Purdue-produced OxyContin, then soon went to work for Purdue for a $400,000 salary. But Holman was not sitting at his desk, for example, whisking premarket tobacco product applications (PMTAs) through the authorization process. In fact, the opposite is true: Holman greenlit millions of marketing denial orders to countless vapor companies, and the even some of the largest players were not spared.

Holman’s departure is emblematic of a broader shift.

“Dr. Holman has spent a substantial portion of his career dedicated to scientific and policy issues that aim to improve public health,” a PMI spokesperson said in a statement to Filter. “He is committed to helping existing adult smokers access scientifically substantiated smoke-free alternatives while protecting youth. We are looking forward to him joining our team as we continue to pursue a smoke-free future.”

Holman’s departure is emblematic of a broader shift. Scientists, engineers and policymakers are becoming more willing to jump ship to Big Tobacco, as these demonized companies, with their histories of cynical deceit around the harms of cigarettes, transition toward safer nicotine alternatives like vapes. (In May, Kegan Lenihan—a former chief of staff at the FDA—joined PMI to become the vice president of government affairs and public policy, and head of its DC office.)

Holman, who has spoken on panels at the E-Cigarette Summit, has always seemed supportive of the the FDA’s “continuum of risk” strategy, which was frequently touted, if not substantially acted upon, by the agency’s former commissioner Scott Gottlieb. It’s the notion that certain nicotine products—like e-cigarettes, heated tobacco devices and oral tobacco—are less harmful than combustible cigarettes and that adult smokers should be encouraged to switch if they’re not able or willing to quit nicotine.

“It’s extremely good news and a bold and inspired move by Holman,” Clive Bates, the former director of the United Kingdom’s Action on Smoking and Health (ASH), told Filter. “He’s always been someone trying to do the right thing and act with integrity, albeit within the confines of the FDA and the Tobacco Control Act.”

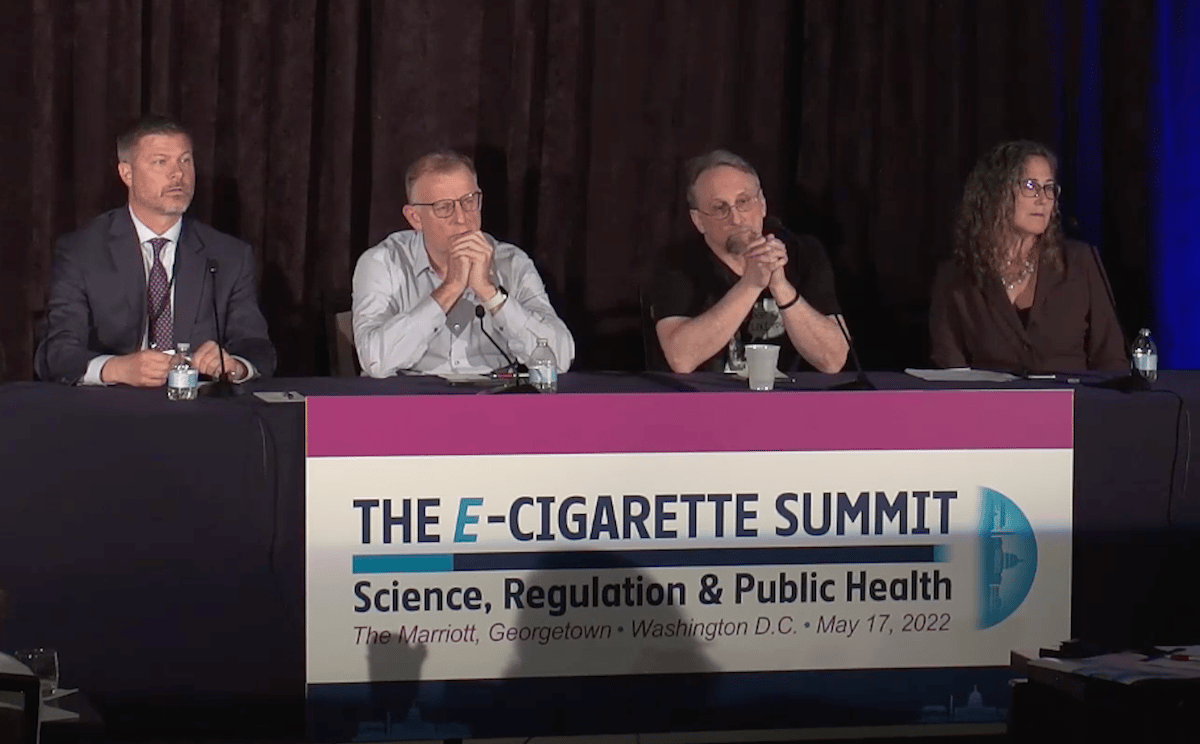

Bates and others grilled Holman at the most recent E-Cigarette Summit in May, where Holman hotly contested criticisms by citing the legal restrictions under which he and his FDA colleagues were working.

“The move sends a massive pro-harm reduction signal by recognizing that tobacco companies will be prime movers in the endgame for smoking,” Bates continued. “Holman is the highest-profile regulatory professional to understand and endorse that reality. He will not be doing anything on combustible products other than working night and day to phase them out with much safer alternatives. He is bound to be attacked by the anti-tobacco activists, but what he is doing is ethical and grounded in credible public health motives.”

Some in tobacco control and within the industry, all of whom requested anonymity so as not to affect their careers, suggested to Filter that Holman could have been gunning to be the new director of CTP, a role left vacant when Mitch Zeller retired in April. The job ultimately went to Brian King, formerly of the Office on Smoking and Health (OSH) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), who has been endlessly criticized for failing to correct the record on “EVALI.”

Others wondered, too, if Holman had grown more and more disillusioned by the agency, which has had its plans blown up on countless occasions by trigger-happy legislators pounding the drum about the so-called youth vaping “epidemic.”

Holman did not respond to Filter’s request for comment. Zeller declined to comment via email.

The PMI spokesperson also told Filter in a statement that “Dr. Holman will abide by all post-employment restrictions.”

Holman’s inside knowledge of the CTP is likely to be a gold mine for PMI as it navigates regulatory challenges.

“These restrictions prohibit Dr. Holman from appearing before or communicating with the FDA on behalf of PMI regarding any matter for a period of one year,” the statement continued. “In addition, Dr. Holman is prohibited for a period of two years from appearing before or communicating with the FDA on behalf of PMI regarding any matter that was pending under his official responsibility during his last year of government service. Finally, Dr. Holman is permanently prohibited from appearing before or communicating with the FDA on behalf of PMI regarding any particular matter in which he was personally and substantially involved during the entirety of his government service.”

However, speculation has swirled that PMI will at some point soon file a number of PMTAs and try to make a substantial splash in the United States: Recently, PMI and Kavial Brands agreed to an international licensing agreement that will allow PMI to “manufacture, sell and distribute the Bidi Stick”—a disposable vaping product—in markets outside of the US, and another PMI-owned e-cigarette, Veev, has already launched in select markets across the globe. PMI is also closing in on a deal to purchase Swedish Match as well.

Holman’s inside knowledge of the CTP is likely to be a gold mine for the company as it navigates these regulatory challenges.

“PMI claims it is in the process of a fundamental transformation to far less hazardous products,” David Sweanor, a tobacco industry expert and chair of the Advisory Board for the Centre for Health, Law, Policy, and Ethics at the University of Ottawa, told Filter. “If this is a sincere effort, Holman can facilitate a change that has huge public health benefits. If insincere, people like Holman are very well positioned to realize that and potentially call out the company on its irresponsibility. Either way, public health objectives can be advanced.”

Screenshot from the E-Cigarette Summit stream showing, from left to right, Matthew Holman, Clive Bates, Marc Slis and Professor Kathleen Hoke

The Influence Foundation, which operates Filter, has received grants from PMI and Juul Labs, Inc. Filter’s Editorial Independence Policy applies.

Show Comments