The annual E-Cigarette Summit in Washington, DC, is perhaps the most eclectic conference in tobacco control. Consumer advocates, vape shop owners, academics, researchers, regulators and industry executives all gathered on May 17, as they have for the past several years.

Perhaps more than anything, the conference is a rare opportunity to publicly levy questions at higher-ups in the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), an agency not known for its transparency. So it didn’t take long for attendees to rise during the Q&A sessions and ask Matthew Holman, the director of the Office of Science at the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products (CTP), and Kathleen Crosby, the director of CTP’s Office of Health Communication and Education, why the FDA has continued to communicate so poorly the “continuum of risk”—the idea that some nicotine products are significantly safer than others.

That became the theme for much of the afternoon: Now that the FDA was finally authorizing some vapor products through its often-criticized and onerous premarket tobacco production application (PMTA) process, why was the public still so massively misinformed about e-cigarettes?

Two of the most prominent speakers—David Ashley, a former director of the Office of Science at CTP, and Vaughan Rees, the director of the Center for Tobacco Control at Harvard—both acknowledged that vaping had a place in ending combustible smoking.

“What’s the ethics of doing that—misleading people to get behavior change?”

Marc Slis, a vape shop owner in Michigan, gave a fiery speech about how the FDA’s bureaucracy was driving adults back to cigarettes. Robin Mermelstein, a distinguished professor of psychology at the University of Illinois Chicago, applauded previous tobacco control efforts but urged more nuance in communicating the relative risks among nicotine products.

Dr. Jasjit Ahluwalia, a physician and public health scientist at Brown University, referenced a recent study that suggested 60 percent of doctors in the US think nicotine causes cancer, and argued that the FDA wasn’t just failing to combat the misinformation, but may even be contributing to it. Since so much public messaging on vapes now revolves around mental health, he pointed out—referencing Crosby’s earlier presentation about the FDA’s linking nicotine withdrawal to short-term anxiety and depression in its youth prevention campaigns—people might easily start to believe that nicotine is the direct cause of those conditions.

Crosby responded that her department is careful to link short-term anxiety and depression to nicotine withdrawal, not nicotine itself. Yet Ahluwalia urged better messaging, even comparing the FDA’s communications with those of the Truth Initiative, the prohibition-leaning nonprofit. Truth has plastered the internet and empty storefront windows with fake advertisements for a “Depression Stick,” a satirical vaping product whose name purports to be honest with the user.

Clive Bates, former director of the United Kingdom’s Action on Smoking and Health, asked panelists if many in tobacco control simply had it backwards—was nicotine not a cause of anxiety and depression, but a treatment?

“Is it ever right to exaggerate risks to get the behavior change you want?” Bates continued, to a round of applause from the audience. “Is it okay to imply, by omission or commission, that vaping is as harmful as smoking just because you want to deter young people from using these products? What’s the ethics of doing that—misleading people to get behavior change?” His question was answered not by the FDA representatives, but by Dr. Kevin Gray, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Medical University of South Carolina, who said that nicotine was not a good way to modulate those unpleasant feelings.

“Despite what people like you think, we do try our best to communicate that stuff.”

In a space intended to open up constructive dialogue, the frustration of the audience—and the panelists—was typically palpable. Slis, the vape show owner, lambasted the PMTA process while sharing a stage with Holman, who repeatedly deflected, implying there was only so much under his and the FDA’s control.

“Go down the hill here to the Capitol, because they wrote the law,” Holman said. “We have jurisdiction over the product[s] that Congress gave us jurisdiction over, [and] we just got jurisdiction over synthetic nicotine. We didn’t choose that. Congress wrote a law, and now we’re responsible for implementing it.”

Sitting next to Holman on the panel, Bates conceded the point to an extent, but suggested that that FDA has far more space to interpret its implementation of laws—and conduct its communications—in a way that supports harm reduction.

“There are a lot of restrictions on what we can say, how we can say it, the process we have to go through in order to say it publicly that are really challenging,” Holman said. “And despite what people like you think, we do try our best to communicate that stuff.”

“No,” Bates deadpanned. “I do think you try your best.”

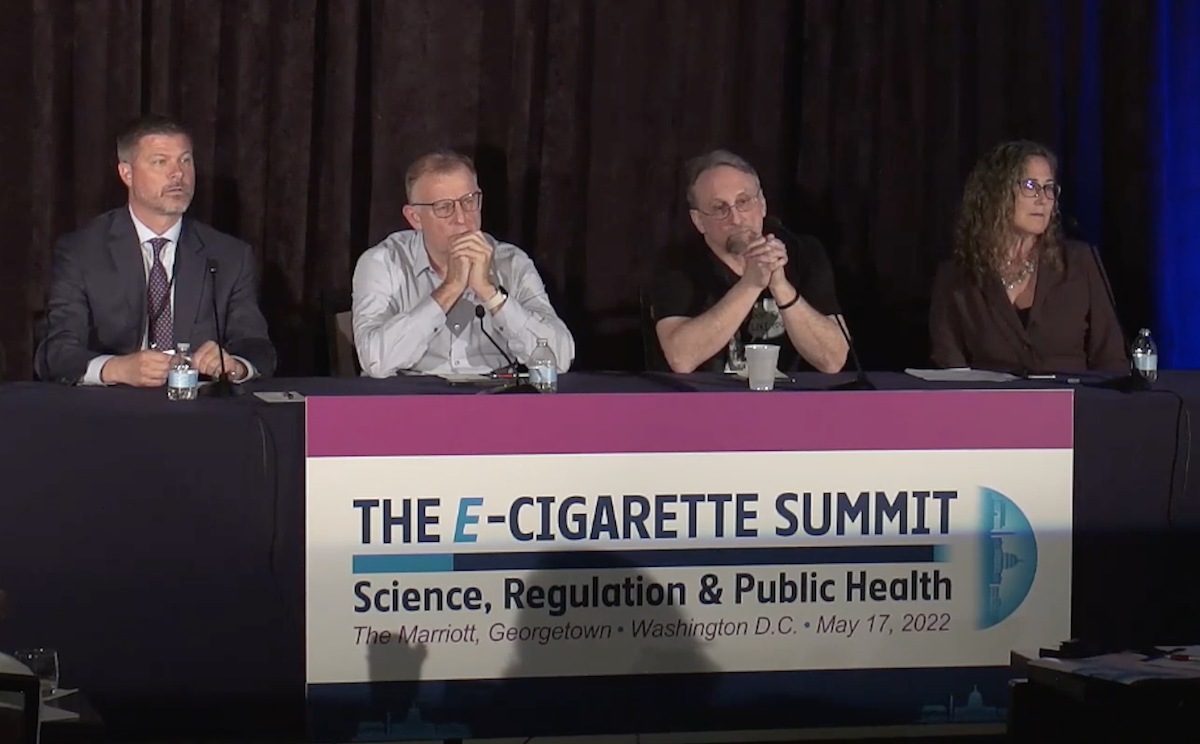

Screenshot from the E-Cigarette Summit stream showing, from left to right, Matthew Holman, Clive Bates, Marc Slis and Prof. Kathleen Hoke, JD

Show Comments