A common misconception about people who use heroin is that they all want to get as high as possible, that everyone wants to arrive at that sleepy-eyed nod that movies depict immediately following an injection. But many people with an opioid dependency use only to stave off symptoms of withdrawal, and therefore actually want as little of a high as possible.

Since the synthetic-opioid fentanyl began augmenting or replacing heroin across North America, controlling your dose has become increasingly difficult. Every bag of “heroin” purchased on the street is of an unknown purity. Amid sky-high fatality rates, fentanyl is making many bags stronger than anybody wants.

An older heroin user in Seattle who goes by the nickname JD told Filter that he struggles to achieve the milder high he’s after.

“So many people who hit that heroin, shooting it in their arm, they nod and they be so deep, they forget everything,” he explained. “I don’t want to do it like that. I stay on point.”

For six or seven years now, JD has visited the People’s Harm Reduction Alliance (PHRA) in Seattle’s University District. He was standing outside their office one morning with a few other guys, waiting for the door to open, and a friend told him about something new that PHRA was experimenting with. He suggested it might be what JD was looking for.

“It’s called the hammer,” his friend said. “It’s a heroin pipe.”

JD gave it a try.

“It don’t make my stomach all upset like the needle does,” he said. “It doesn’t make me sick. It doesn’t make me nod. So I like it.”

“If we could create something that was actually a better product, we could give North Americans a means to switch from injection.”

Many of the most effective responses to the drug war’s new era of synthetics have emerged from the minds of people who use drugs. Filter has covered how drug users are at the front of naloxone distribution, for example, and how groups in Canada are organizing “buyers clubs” to bulk-purchase opioids of a known purity.

Now Shilo Jama, a longtime organizer in Seattle, hopes to offer a tool that gives people who use heroin greater control.

“My feeling was, if we could create something that was actually a better product, we could give North Americans a means to switch from injection,” said Jama, who co-founded PHRA and has also written for Filter. “If we could find a pipe that worked well enough, that could bridge a gap.”

On a 2018 trip to Portugal, Jama noticed that many younger heroin users were reluctant to try needles and instead smoked their opioids using tinfoil. “But tinfoil always felt inefficient to me,” he continued. “With tinfoil, you’re getting the entire area around you high. Smoke is leaving every which way.” And this could be a disincentive to smoke, rather than inject. “So I felt like we could build a more efficient system.”

Jama began looking around. Small glass pipes specifically designed for the inhalation of crystal methamphetamine and crack cocaine have existed for many years. The former is typically a straight tube and the latter a tube with a bubble on one end. They can work for heroin for a short time but clogging is a problem.

“Mother of God, this is way more complicated than I thought.”

“Next, I started looking at old opium dens and opium pipes,” Jama said. Antique designs, however, proved prohibitively expensive. Working with a glass company that Jama asked should remain anonymous, he began experimenting with different prototypes and collecting feedback from members of the Urban Survivors Union, a national nonprofit run by people who use drugs that Jama also co-founded back in 2009.

“We went through a long design process,” Jama recounted. “Mother of God, this is way more complicated than I thought,” he remembered thinking. “There was a lot of trial and error and, eventually, we got to the final design, which looks like a little hammerhead.”

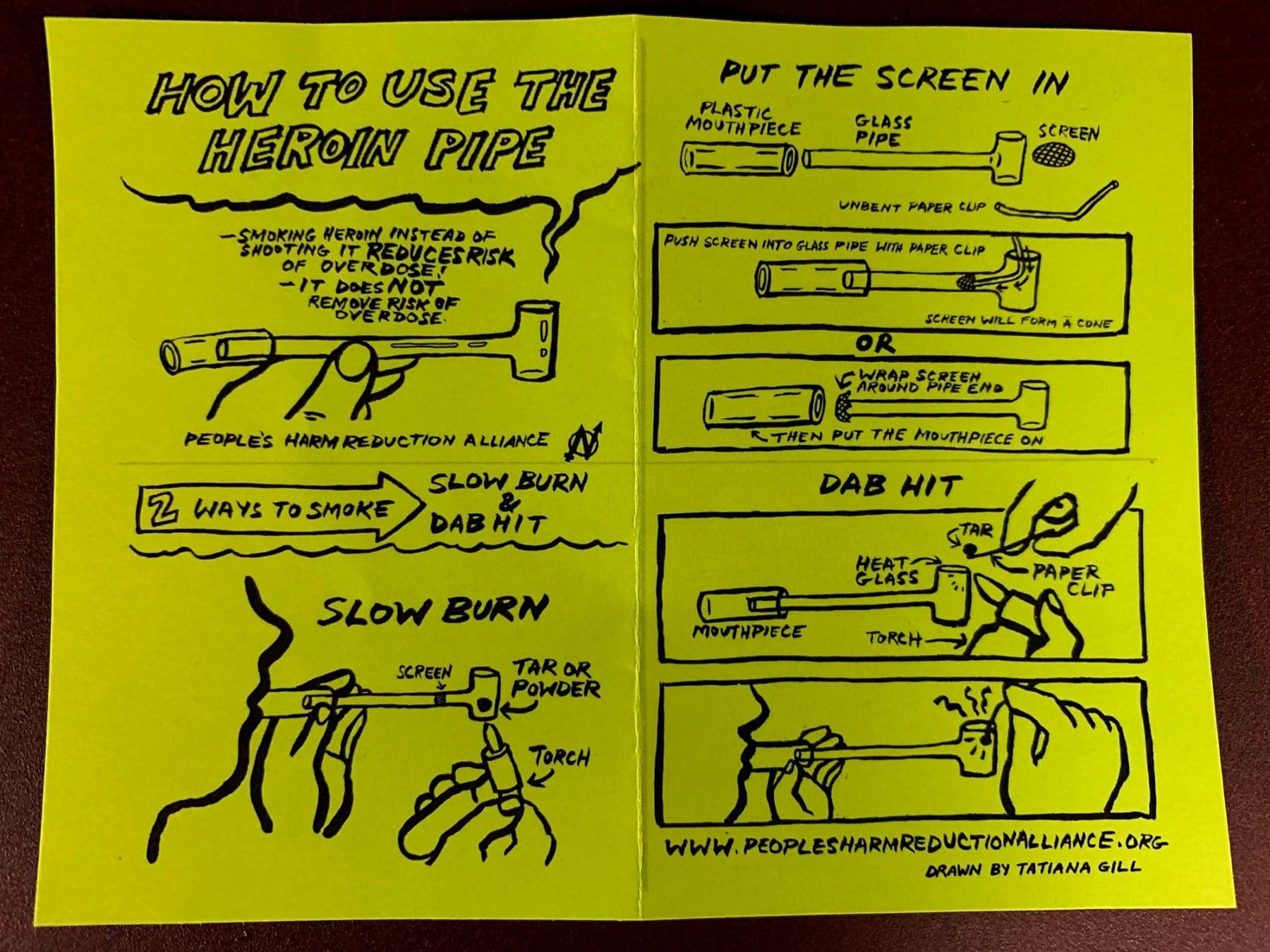

The resulting design.

PHRA’s heroin pipe can work for powdered “China white” but was designed for Washington State’s “black tar” heroin, which has a viscous consistency that’s just about impossible to snort. The pipe consists of a longer tube that feeds into a shorter tube connected at a right angle. At the bottom of the shorter tube is where the heroin goes in, and where you apply a lighter from underneath. A replaceable screen placed at the pipe’s junction prevents clogging.

Overdoses were at the front of Jama’s mind when designing the pipe. But, as with so many harm reduction programs, a number of unintended benefits are increasingly apparent.

McMahan said that the pipes are a less harmful way of ingesting drugs compared to syringes.

Vanessa McMahan is a researcher with the University of Washington’s department of medicine. Together with Tom Fitzpatrick, a PHRA co-founder and medical doctor, she’s working to evaluate Jama’s heroin pipes via a six-month study. It’s based on information that PHRA collected both before and after the device’s beta rollout in Seattle’s University District.

The numbers remain raw but, overall, said McMahan, the data look encouraging. Since the end of June 2019, PHRA has distributed roughly 4,400 of the heroin pipes.

McMahan said that the pipes are a less harmful way of ingesting drugs compared to syringes, for the obvious reason that syringes carry a heightened chance of infection. Because needles involve bodily fluids, it is easy for them to spread diseases like hepatitis C and HIV/AIDS plus bacterial infections that can lead to abscesses and cellulitis. With pipes, those risks are minimized.

Shilo Jama (left) with Vanessa McMahan and Tom Fitzpatrick.

Shilo Jama (left) with Vanessa McMahan and Tom Fitzpatrick.

Other benefits were less expected or are less obvious.

“These pipes are a way to include people who smoke opioids in our programing,” McMahan said.

“For a long time, needle exchanges have worked with people who inject substance. But people who smoke substances have not been able to get the same level of services.”

“Now there are people who come to the needle exchange for a [heroin] pipe and that might be the only place that they get any [health] service,” she continued. “So it’s not just a pipe program. It’s a way for people to connect with testing, referrals for treatment, or referrals for health-insurance navigation. First and foremost, having a pipe program is inclusive.”

PRHA’s heroin pipes have caught the interest of three broad categories of drug users.

Only a small percentage of Americans ever use a needle to inject drugs. But studies have shown that those who do are at a higher risk of adverse health outcomes. According to the US government’s Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), an estimated 4.48 million people in 2018 had used a needle to inject drugs during their lifetime, up slightly from 4.44 million the previous year. Of those 4.48 million people in 2018, some 2.36 million had injected heroin in their lifetime. Meanwhile, an estimated 2.12 million had smoked heroin.

Jama said it appears that PRHA’s heroin pipes have caught the interest of three broad categories of drug users. The first is the relatively-new opioid user who has never tried injecting drugs. For them, the hope is that the heroin pipe will increase the length of time they refrain from injecting or prevent them from transitioning to injecting all together.

The second group is older drug users who have been using needles for a long time and who might struggle with health issues as a result. “They can transfer to smoking, let their body heal, and then they can make their own decisions,” Jama said.

The third group consists of people who are injecting drugs who might want to taper their use as a step toward abstinence. “If they can transfer to smoking, they might be able to reduce their use,” Jama said.

He described the pipe project as the definition of harm reduction. “At its core, it reduces harm.”

Around PRHA’s headquarters in Seattle, JD said the heroin pipes are beginning to attract attention.

“The ladies, they are really interested in it,” he noted. “They like that it’s clean, without all the mess of the foil paper. A bunch of them are trying to get away from the needle, even if they use the pipe and still use the needle sometimes. So it’s good.”

All photos by Shilo Jama, who retains the rights.