The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first generic versions of Vyvanse, the prescription stimulant known for being “abuse-deterrent.” The change was not prompted by the ongoing shortage of ADHD medications in the United States, but comes amid increased surveillance of both licit and illicit stimulants.

Vyvanse is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant manufactured by Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and is FDA-indicated for binge-eating disorder in addition to ADHD. Since being approved in 2007, it’s remained under one or more patents; until August 24, when the last one expired. The generic drug, lisdexamfetamine, is now fair game for the slew of pharmaceutical companies that have been circling.

The fact that Vyvanse is no longer under patent doesn’t mean that supply will no longer be vulnerable to shortages; Adderall went generic in 2009. But competition will make Vyvanse progressively more affordable.

As the Adderall shortage deepened, demand for similar ADHD medications increased. Takeda announced a shortage in June, but Vyvanse has been intermittently backordered since late 2022, especially in the larger pharmacies.

The FDA has official labeling for designating “abuse-deterrent formulations” (ADF) of opioid analgesics, but no equivalent labeling for CNS stimulants even though the agency has been actively interested for several years. But Vyvanse is essentially marketed as ADF, even if there’s no formal infrastructure to do so.

Vyvanse is always extended-release, unlike medications like Adderall that have both short- and long-acting versions. Capsules that get broken down by your stomach acid to release the contents slowly do make the FDA and broader health care industry view them with a bit less suspicion.

Vyvanse’s unofficial ADF status is often attributed, mistakenly, to the fact that you can’t crush up a capsule—which is silly because you can simply open them. Even the FDA doesn’t have a problem with patients opening up the capsules if the powder is easier to consume that way. Generic versions coming to market include chewable tablets, in addition to capsules.

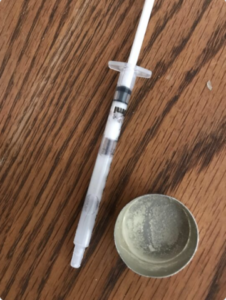

Vyvanse mixed with water

What’s set Vyvanse apart is that it’s a prodrug, which means its psychoactive ingredients aren’t actually active at first. Opioids can be formulated as prodrugs too; tramadol and codeine are common examples. Vyvanse was the only ADHD prodrug medication up until 2021, when the FDA approved Azystarys—a prodrug of methylphenidate, the psychoactive compound in Ritalin.

The stimulant part of Vyvanse has been hitched to an amino acid. When you take a capsule orally and send it on its way down your gastrointestinal tract to your small intestine, that process breaks it down to release the active metabolite: dextroamphetamine, at which point it’s functionally the same thing as Adderall.

People who haven’t tried to get Vyvanse into their bloodstream via some other, faster route of administration—which normally would be all of them—often say that doing so doesn’t have any effect. Injecting or boofing or snorting it definitely does have an effect, but essentially you’re sending the drug on a journey all around your bloodstream before it gets to your liver and converts into something more bioavailable.

Some of it will get absorbed along the way, but it’s a slower and more diffuse process. Personally I get less effect out of boofing and snorting than just from swallowing the capsules whole—but more out of dumping the contents into a drink.

Vyvanse distinguished itself in 2007 by focusing specifically on “Drug Liking Effects,” and demonstrating how it produced less of them compared to the FDA-approved stimulants at the time. In the US, branding a medication as one people don’t like is good business. Zevra Pharmaceuticals, the same company that makes Azystarys, has a prodrug in development to treat stimulant use disorder, too.

Photographs courtesy of Kastalia Medrano

Show Comments