I thought I was too old to have to worry about being raped in prison. But as his sweat dripped onto the back of my neck, the weight of his body holding the blanket that pinned my arms, I thought: Am I dreaming? No, this was real pain; real smells; real sensations.

In my 27 years of incarceration I’ve been in nine different prisons, and at eight of them queer and trans prisoners weren’t empowered by any kind of support system, even informally. We’re preyed upon by the gangs, and we’re preyed upon by the staff. Power respects power, and we had none.

This changed after I came to South Central Correctional Facility (SCCF), a private medium-security prison in Tennessee. SCCF is the birthplace of Be the Change (BTC)—the first, and we believe only, openly LGBTQ community in any of the state’s 14 prisons.

“They were just [isolating] people in ‘gay or trans’ cells that did not want to be there.”

Tavaria Merritt is 12 years into a 50-year sentence at SCCF. She was 18 when she went into the prison system, and had not yet come out as gay or trans.

“In [Black] culture, being gay and especially trans is not easily accepted,” Merritt told Filter. “Plus, I was a church kid, and was grounded in a deep religious faith that was in conflict with what I was feeling.”

By 2014 she was publicly identifying as gay, and increasingly aware of the harms queer and trans prisoners were being subjected to, at the hands of both staff and other prisoners. She wrote a letter describing her vision of a community where LGBTQ prisoners could not only find safety and acceptance, but the strength in numbers that would allow them to advocate for themselves.

She made 100 copies of the letter and began passing them out. The rest, she says, is history.

“Before our community began, it was not uncommon for gay or trans prisoners to [enter protective custody], which is a burden on the bed space and prison staff and isolates the gay or trans person from any sort of community,” Merritt said. “They were just putting people in ‘gay or trans’ cells that did not want to be there.”

BTC has around 60 members, but is not part of SCCF’s formal programming because the facility doesn’t allow for prisoner-led organizations. Prisoners are, however, allowed to gather in groups if the event is sponsored by an outside organization. Thus a partnership with Unitarian Universalists has secured BTC a regular Tuesday time slot in the chapel, even though UU never actually shows up.

BTC’s recurring meetings include LGBTQ Update & Opinion Talk, Lifer’s Program, Trans Sisters Group and Overcoming the Habit Class. Though the latter is modeled after 12-step meetings, it takes a harm reductionist approach to drug use—which only makes sense, in an environment where drugs surround everyone at all times.

As BTC has grown, Merritt has given queer and trans prisoners a seat at the table.

“Coming to prison as a pansexual white kid with a sex charge landed me in horribly traumatic and life-threatening situations,” Jason Thomas Stanford, 21, told Filter. “My friends heroin, fentanyl and meth helped me forget … the hopelessness of my situation. I was incarcerated at 17 years old, and by 18 I was given a 20-year sentence. I hadn’t been alive for 20 years.”

In the early days of his sentence, Stanford could see no reason to live. He was sinking under the weight of a particular shame that so many gay and trans prisoners know well—the shame of being known as drug user and sex worker incarcerated on a sex charge.

“Enter, Be the Change,” Stanford said. “This community of love, peace and acceptance is the sole reason I am alive … the acceptance and support demonstrated by [Merritt] awakened something I thought long dead: my sense of self-worth.”

Merritt came out as trans in 2019. As BTC has grown, her charisma and leadership—and tenacity when faced with pushback—has given queer and trans prisoners a seat at the table. SCCF is currently a gang-run facility, a reality that often does not favor LGBTQ prisoners. But because gang leadership recognizes BTC as a unified entity, they’re able to go to Merritt and vice versa whenever there’s an issue to resolve. Power respects power.

Staff hasn’t caused any problems so far. There’s even some talk of giving BTC its own living unit pod, if membership should ever approach the requisite 128 people.

More than a decade after the last National Inmate Survey, the Bureau of Justice Statistics is preparing to conduct the fourth iteration in 2023. The 2011-2012 survey showed that queer and trans people, who are already disproportionately incarcerated, are also disproportionately targeted for sexual violence in prisons and jails. Nearly 40 percent of trans respondents to the survey said they’d been sexually assaulted.

Though sexual and physical assault are still part of life here, they are no longer constant fears. In the space where they’ve receded, there is now room for friendships and hope, and the ability to live a more authentic life. There is community.

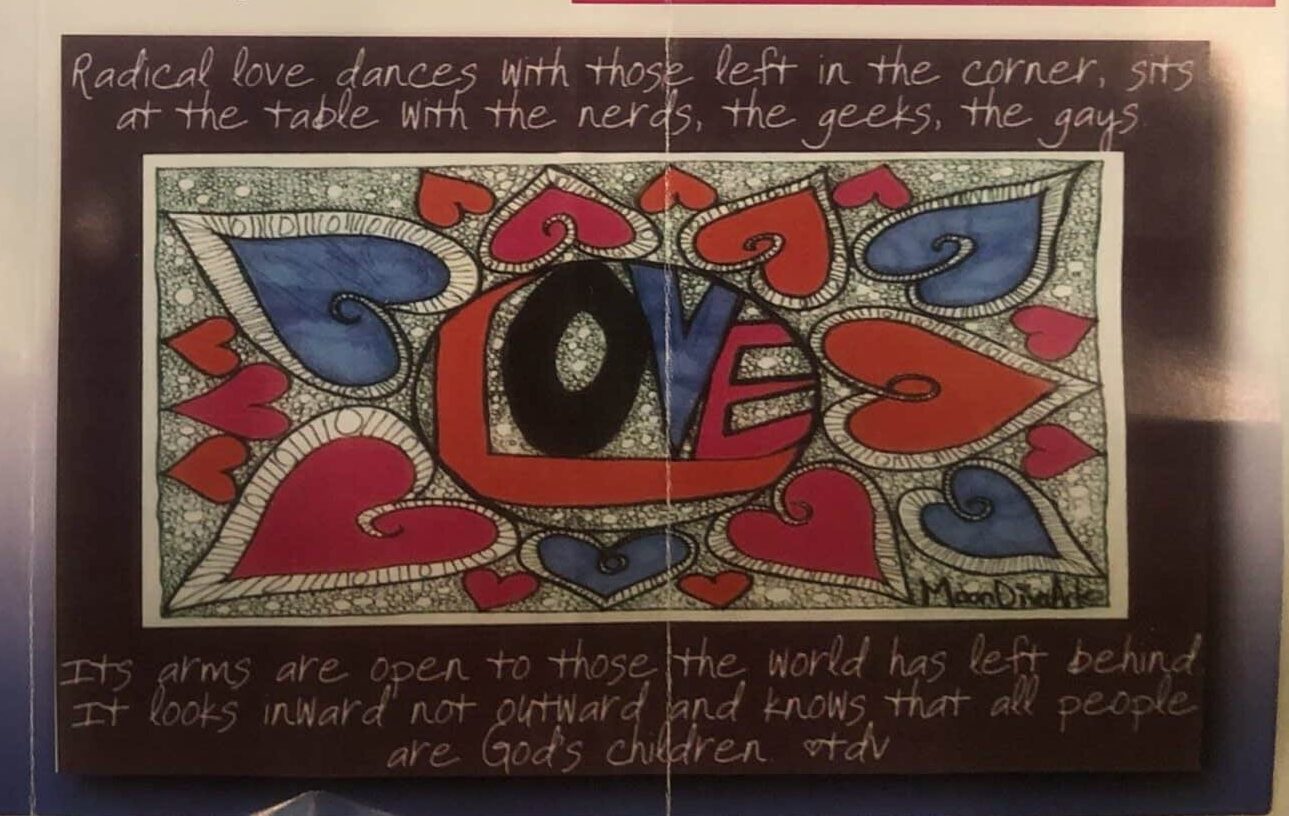

Image courtesy of Tavaria Merritt via Tony Vick

Show Comments