In 2013, the City Council of Grants Pass, Oregon, was looking for a solution to homelessness that didn’t involve providing housing. Law enforcement had already tried putting people on buses and dumping them somewhere out of town, but they just kept coming back. The solution everyone agreed on was to make Grants Pass “uncomfortable enough” that people would leave on their own.

The city ticketed people for sleeping in parks or doorways or alleys or their own cars. They could be fined hundreds of dollars for having pillows or blankets “for the purpose of maintaining a temporary place to live.” If they kept it up, they could be banned from city property, and if they were found on city property after that then they could be criminally prosecuted for trespassing.

The Supreme Court is about to make a decision on whether to uphold Johnson v. Grants Pass, which in 2018 determined that it was “cruel and unusual punishment” to criminalize homelessness for people who don’t have access to shelter; rural jurisdictions often have very limited bed space.

The premise is that sleeping outside is “involuntary” if there’s nowhere else to go; it shouldn’t be a crime unless people have the option of an available shelter bed and choose to sleep outside anyway. But people do choose that, and for good reason.

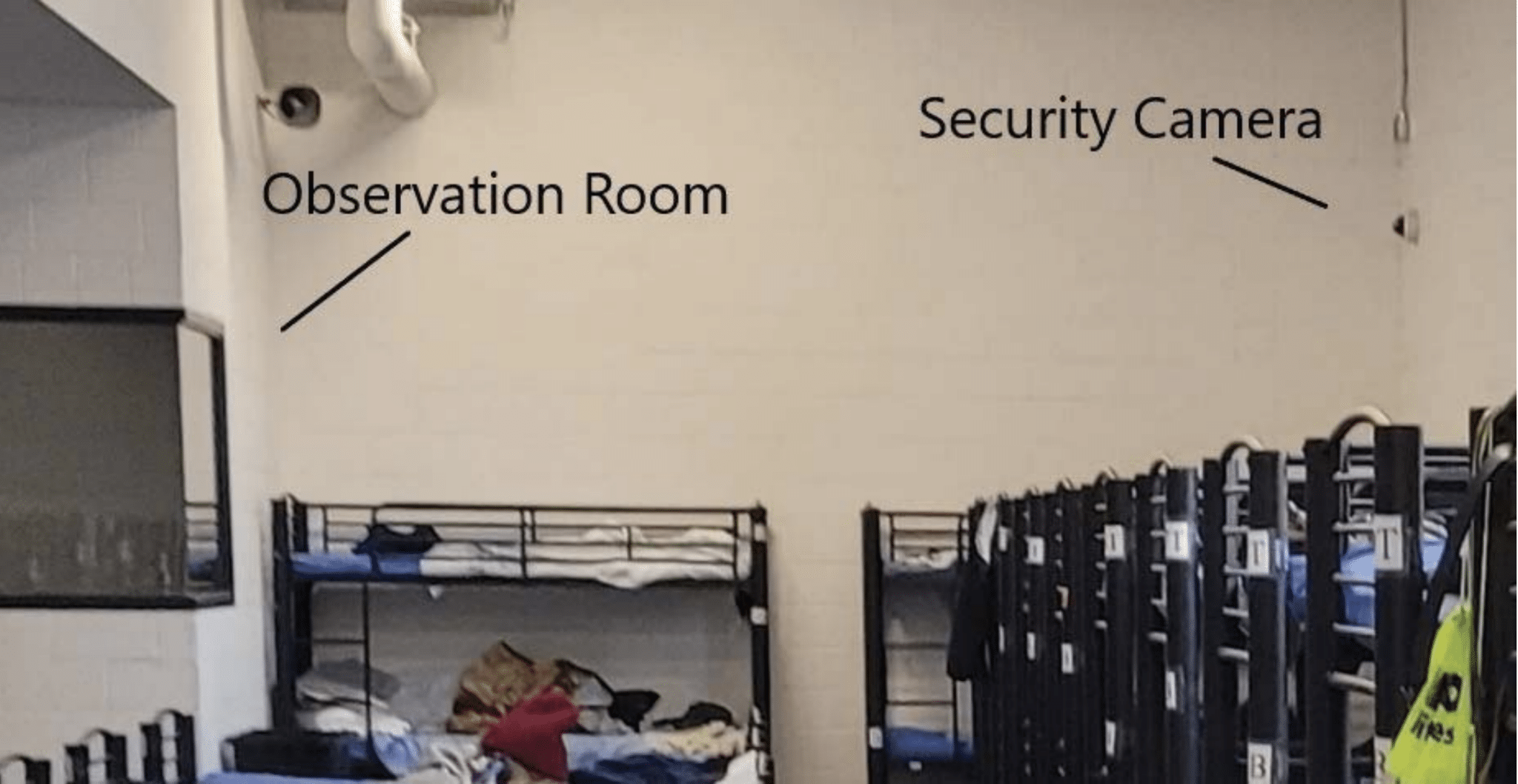

Mass congregate shelters are like the lowest-security form of incarceration.

The Supreme Court decision will set the tone on how homelessness is criminalized nationally, but it’ll directly apply to Ninth Circuit jurisdictions in the West. Before I was sent to prison in 1995, I stayed in a lot of shelters in Washington and California, and a few in Oregon; usually because cops dropped me off there.

Mass congregate shelters are like the lowest-security form of incarceration: work release, where prisoners go out into the community to their assigned jobs during the day and have to return to the facility at night. Though when shelters kick you out at 5 am, but you have to take all your belongings with you to carry around all day.

In recent years, people I’ve known as they cycled in and out of Washington State prisons have described staying at shelters that didn’t feel that different from being incarcerated. Which had surprised them; they’d thought they were free.

When you sleep in these places, you’re under constant surveillance. You’re told when and where you’re allowed to eat, shower, sit down, sleep or make a phone call. Your belongings are searched and often confiscated. You have to check in for the night by 5 pm curfew. After lights out, you’re allowed to use the bathroom, but otherwise have to stay in your assigned bunk. Doesn’t matter if you have homework, or have to study, or have a shift to work somewhere. You get behavioral infractions. You often have to attend group counseling sessions. You often have to work for free.

Many shelter providers require you to do a certain number of hours of work per day or per week, regardless of whether you have an outside job or other obligations. Carwashing, landscaping, gardening, construction work, cleaning, building maintenance, laundry, cooking. One shelter in Washington had me clean fish. A young-adult shelter in Oregon required a full shift in their pawn shop six days a week. A different Oregon shelter once kicked me out for getting a ride back with someone from work. The plan I’d submitted said I’d come back from work by bus.

Encampments are only considered public health hazards because the public can see them.

Staff will track how many times you cuss, have an emotional outburst, are accused of stealing or don’t show up to a scheduled meal. No substance use, even if the substance is legal. You can’t have a pack of cigarettes on you when they go through your belongings, or even smoke outside. People get kicked out for violating those rules all the time. One shelter in Washington made me add up the money I spent on cigarettes in a month, and said if I saved that eventually I could afford an apartment.

Encampments are only considered public health hazards because the public can see them. Shelters are closed spaces the public can’t see into, so they don’t mind whatever goes on inside.

Of course, not all shelters subject people to heavy surveillance. The shelters I stayed at that didn’t feel like prison were mostly the youth shelters. A bunch of street kids ages 12-17 would be locked in a big co-ed dorm with metal bunks and a toilet—but no direct supervision.

When I was in my early teens at these places, I was raped constantly. When I wasn’t being raped or beaten, I was listening to it happen to someone smaller than me. After a while you learned that trying to help made it worse for both of you, so you’d stop.

I always slept outside when I could. It was safer. When I ended up at those places, it was because cops would give me a choice between that and juvie.

If we make it a crime to not go into shelters voluntarily, it erases the main thing separating them from prisons—that you don’t have to stay there. That there’s somewhere else you’re allowed to be.

Image via Utah State Legislature