Smoking has been stigmatized for some time. Once it was normal for idolized film actors, philosophers and writers to be photographed in a cloud of smoke, with a cigarette in hand or hanging off their mouth. Today, people who smoke are often pitied or shamed. Just as tobacco advertising is widely banned, people who smoke have been quietly disappearing from public spaces. Where once just about every pub and many restaurants allowed smoking, the designated smoking area now, for most, is the great outdoors or their own home—if they don’t live in public housing, that is.

People who smoke have literally been sent out of the room. For many, though, smoking is not a vice and not anything to be embarrassed about. It is a choice, one that carries starker risks than many other choices, but also rewards.

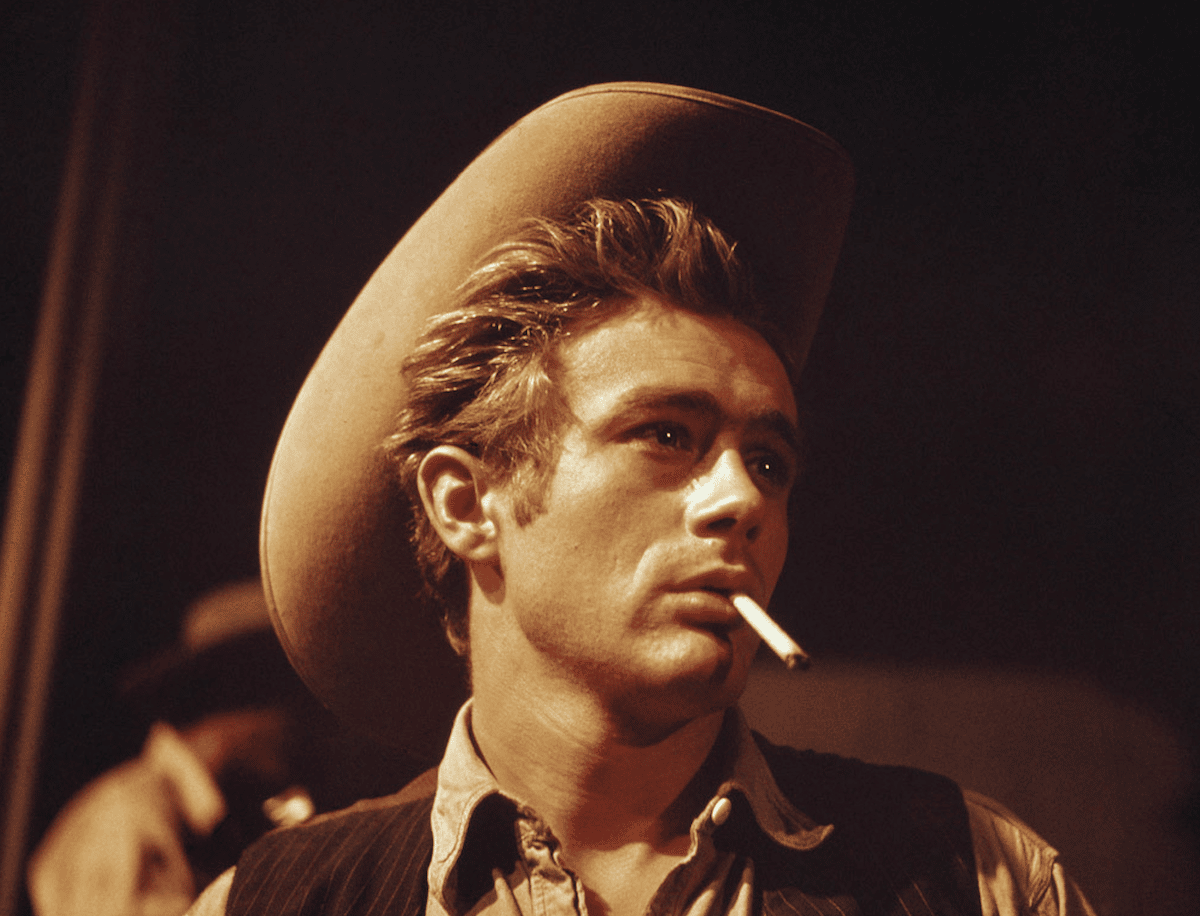

The arts’ love affair with smoking is well-documented. James Dean, Greta Garbo and Humphrey Bogart were often seen with a cigarette, exuding allure and a steely coolness. The British artist David Hockney has smoked for more than 60 years, and is vociferous and stubborn about the essential role smoking has in his life. “A cigarette helps my concentration whenever I stand back from the easel and look at my painting,” he said. “Smoking gives me time to think about the gaze I paint with.”

“I’m 100 percent sure that I am going to die of a smoking-related illness or a non-smoking related illness.”

Hockney feels the “obsession” society has with stamping out cigarettes is “unhealthy,” stating “longevity shouldn’t be the aim in life.” In contrast, he feels he has a rather healthy disregard for his own health: “I’m 100 percent sure that I am going to die of a smoking-related illness or a non-smoking related illness.” Hockney now lives in Normandy in France, where he says he can smoke more freely.

Smoking has always had its place in the world of bohemia. French existentialist philosopher, novelist and playwright Jean-Paul Sartre smoked pipes, cigarettes and cigars; for him, smoking was a way to experience the world. Whether he was going to the theater or discussing ideas with his friends, having a cigarette in hand elevated his experience. His life was intensified and clarified when it was wrapped up in a smoky haze. He said: “Whatever unexpected happening was going to meet my eye seemed to me that it was fundamentally impoverished from the moment that I could not welcome it while smoking.”

It is evident that smoking can be harmful to others as well as to the person smoking, which complicates the ethics, but what if it’s done privately? Should we stop people from smoking as a way of protecting them from themselves, as the proposed US menthols ban seems to conceive?

We don’t bar people from risky hobbies such as rock climbing or playing rugby. However, rock climbing and rugby can easily be viewed as healthy and beneficial pursuits; we can see beyond the risk that they involve. Whereas the high risks of smoking are well known, and the pleasures of drug use are readily removed from the calculus. Few would claim health benefits from smoking, although mental health studies have shown, for example, that nicotine can help ease attention deficit that occurs with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses.

Pleasure, as many have argued, is a valid reason to use drugs.

A better analogy, perhaps, is with drinking and eating unhealthy foods. We don’t generally intervene to stop people from drinking quite heavily, often in public; nor do we generally intervene to stop people eating large quantities of red meat, which has been linked to cancer.

Pleasure, as many have argued, is a valid reason to use drugs. That includes nicotine. And while harm reduction is vital—nowhere more so than in the realm of smoking, to which over 8 million annual premature deaths are attributed—it should be done with incentives, access to safer alternatives and respectful communication of accurate information, not with punitive or coercive laws and social pressures.

The prejudice, in some of its other forms, has been easing in the US. In contrast to the stigmatization of smoking, we have seen a shift in attitude toward cannabis and psychedelics. Cannabis is now legal in many states, and in Oregon, where possession of all drugs has been decriminalized, psilocybin has become legal for therapeutic use, with more states expected to follow suit. Compare this with nicotine, where the conversation seems to be stubbed out. In the US, people who tend to smoke are those who are poorer, and are disproportionately from marginalized groups, like members of the LGBTQ or Indigenous communities.

When asked what was the most important thing in his life, Sartre said, “I don’t know. Everything. Living. Smoking.” And Hockney’s description of smoking as a “deep pleasure” would be recognized by many others. Are we entitled to argue that their lives would have gone better if they’d never smoked?

Hockney sees the campaigns against smoking as emblematic of a world that’s turned “bossy.” This is, essentially, a complaint about paternalism—treating adults as if they were children, for their own good, making them feel ashamed and forcing them to indulge out of sight.

The English philosopher John Stuart Mill argued that limits to an individual’s freedom should apply when their behavior causes harm to another. Adults should feel free, he believed, to engage in what he called “experiments of living,” to include things that could harm them but don’t harm others. He believed that an individual, without dependents, should be free to drink himself to death if he wanted to. Other people could urge him not to, but they—and the state—shouldn’t coerce him to stop drinking. This harm principle was articulated in his essay, On Liberty, published in 1859.

Would Mill deny Hockney the right to light up at one of his art exhibitions? Yes, he probably would, on the grounds that that passive smoking is harmful. People who hadn’t chosen to smoke could suffer some harm from being in the same room as Hockney. But an outdoor space, like a gallery doorstep—which these days would likely have a sign saying you can’t smoke within 20 feet of the building—would be a different question.

The harm reduction message on smoking cannot merely be “stop,” any more than it should be for people who use drugs from the adulterated illicit supply.

In Austria, the right-to-smoke argument briefly held sway in 2018 when a proposed government ban on smoking at restaurants, bars and cafes was revoked. That decision was, however, overturned a year later, on the grounds that the government had an obligation to protect public health and that protecting public health was incompatible with tolerating smoking in public places.

People who smoke don’t smoke because it’s unhealthy. They smoke because, to them, it feels good. Clive Bates, a tobacco harm reduction activist, considers graphic warnings on cigarettes and packaging to be nothing more than a form of stigmatization. Regarding the idea of putting warnings on individual cigarettes, he wrote that it was “essentially a stigmatizing measure designed to make smokers feel stupid and to force them to parade it as they smoke.”

All of which speaks to how we should communicate about lifesaving forms of tobacco harm reduction, like vapes. There’s a critical difference between sharing accurate information and resources to encourage people to stay safer, versus trying to shame or scare people into modifying their behaviors. Harm reduction is about saving lives, but it is equally about agency—empowering people to make their own best choices. The harm reduction message on smoking cannot merely be “stop,” any more than it should be for people who take the risk of using drugs from the fentanyl-adulterated illicit supply.

We all know that long-term smoking carries severe risks. It’s written on the packet. But we don’t need to protect adults who smoke from their own ignorance about that, because they aren’t ignorant. Where people have been woefully misinformed by many authorities is on the relative safety of other ways of consuming nicotine, which many people who try them come to prefer to smoking. Like Hockney, many want to be free to make their own choices. Instead of stigma, we need an open and unfettered discussion.

Photograph of James Dean by Insomnia Cured Here via Flickr/Creative Commons 2.0

Show Comments