In 1996, the Prison Litigation Reform Act was enacted in response to the rising number of lawsuits prisoners were filing in federal court. Not by addressing the alleged civil rights violations themselves, of course, but by making the court system significantly less accessible to prisoners: relegating our complaints to the realm of corrections departments’ grievance processes, making us responsible for more fees, etc.

So successful was this at reducing the volume of “frivolous” litigation that corrections departments around the country have come to understand that whatever the minimum required living space they were supposed to allocate—50 square feet per person, or 35 square feet unencumbered, or what have you—no one would get in trouble if they decided we didn’t need all that space.

Amid the United States mass incarceration crisis, the term “overcrowding” is used a lot. It’s indeed true that in many carceral institutions, especially local jails, people are being packed in past maximum capacity. But in many others, especially state prisons, the issue isn’t necessarily that there are more prisoners than beds—it’s that there are exponentially more prisoners than corrections officers (COs).

Understaffing doesn’t technically constitute overcrowding, but functionally that’s what it amounts to: a facility containing more prisoners than it has the capacity to keep safe.

Understaffing in state prison systems is a national crisis, but few exemplify it better than the Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC), where I’ve been incarcerated for the past three decades. We were already being stacked three deep in single-occupancy cells while beds across the state stay empty. After the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the COs vanished.

That in and of itself can make our living space smaller. When there aren’t enough COs to cover the whole facility, often they’ll just cram you into smaller and smaller sections of that facility. That makes for more fighting; more COs quitting after their first week; more prisoners sleeping outside; and deaths from murders and suicides at an all-time high.

In June 2020, the overnight shift for my 1,000-plus capacity prison consisted of three COs. A unit manager (out of uniform) would operate the radio and gate controls. A lieutenant and a sergeant would take turns driving the perimeter patrol car and walking from one side of the camp to the other once every four hours.

Once a few COs trickled back in, things got worse. Whereas previously doors were simply being left open, now they’re locked while one CO paces the facility making sure they stay locked, and still no one is posted to the living units where they’d be able to hear calls for help.

Supplementary oxygen, for instance, is stored at officers’ booths where no officer sits to retrieve it. One night around 10 pm, Hank*, who smoked heavily, had a COPD episode where it got harder and harder to breathe. Calls for help went unanswered.

One of Hank’s friends started trying to break the window to reach the oxygen, and that noise did prompt a lieutenant to appear, but he couldn’t find the key to get into the booth. Prisoners carried Hank, who could no longer speak by this point, over to medical.

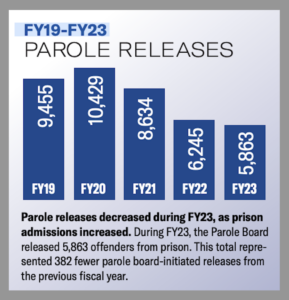

After a few years of trending downward due to pandemic barriers, the GDC prisoner population is beginning to tick back up. But the pandemic never compelled the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles to consider releasing more people.

The definition of “overcrowding” to reflect the landscape of prisons today matters, because it’s what Georgia’s governor can use to declare a state of emergency, which would—in theory—compel the Board to let enough of us out to so that the population didn’t exceed maximum capacity. But capacity is currently defined by bed space, and there are plenty of beds. It’s time to update it to also require a CO:prisoner ratio of 15:1, as the Federal Bureau of Prisons recommends.

In early 2024, an informal survey of people incarcerated across 10 of GDC’s 34 prisons, including four of the seven high-security facilities where violence has escalated the most, the estimated ratio was 100:1. GDC did not return Filter‘s request for comment.

The Board can grant parole to anyone over 62, even those sentenced to life without parole.

Once a prisoner turns 62, by the authority of the Georgia state constitution the Board can parole them out without requiring they meet any further criteria. They can do this for anyone over 62, even people sentenced to life without parole. But they don’t, because they don’t have to. It’s a criminal-legal system tradition to not actually requiring law enforcement to do the humane thing, but simply offer them the option.

So the prisoner population continues to grow older, and the Board carries on behind closed doors without ever having to explain its denials. The Board did not return Filter‘s request for comment.

People linger in solitary confinement because your constitutional right to shower or see the sun every once in a while goes away when there’s no one around to unlock the door. Vital medical treatments get put off indefinitely because no officers can be found to escort the patient to an outside medical facility. The 15 minutes between required check-ins for people on suicide watch last… longer. Tasers and pepper spray are used casually. The dead are left on the floor. Toilets stay clogged.

GDC has been unable or unwilling to actually hire and retain staff at the levels required to operate its facilities. The ongoing Department of Justice investigations into conditions inside those facilities have not made the department any more inclined toward transparency. The Board, meanwhile, has the power to actually fix the problem, but if its members were going to do let us out of their own accord, they’d have done it a long time ago.

Top photograph and inset graphic via Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles

*Name has been changed to protect source.

Show Comments