The federal government wants to weaken confidentiality rules for patients with addictions. This means people who have been in any kind of treatment—even years ago—but will mainly affect methadone patients.

Patients who have been treated for substance use disorder (SUD) are currently entitled to consent—or not—to the release of their information, under 42 CFR Part 2. This decades-old law has been under threat for some time—about 10 years, in fact, ever since electronic health records (EHR) and Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs), to track prescribing of controlled substances, proliferated.

All prescribed substances go into the PDMP—except for medications dispensed by opioid treatment programs (OTPs), better known as “methadone clinics.”

Why? Because a 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), which regulates OTPs, told them to check PDMPs for their patients, but not to input their data. So methadone dispensed for opioid use disorder (OUD) stays out of the records system; federal law requires individual written consent to release SUD patients’ records.

But now—in the context of all regulatory authorities wanting to get rid of that consent provision by turning 42 CFR Part 2 into HIPAA, which has no such requirement—SAMHSA is formally proposing a regulatory change.

Sometime in May, SAMHSA quietly sent over its proposal to the US Office of Management and Budget, which governs rulemakings to determine if they impact finances. There was no announcement, and I only found out thanks to a tip.

We don’t know precisely what the proposed rule will say; it’s currently in review. But the summary on OMB’s website makes the broad intent clear:

SAMHSA is proposing broad changes to Confidentiality of Alcohol and Drug Abuse Patient Records, 42 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 2, also known as 42 CFR part 2 to remove barriers to coordinated care and permit additional sharing of information among providers and part 2 programs assisting patients with substance use disorders (SUDs).

It’s interesting that this is coming from SAMHSA, which has said for years that it’s up to Congress to change the statute. But SAMHSA has already used subregulatory guidance and rule changes to make much of CFR Part 2 meaningless—most recently allowing information-sharing for “health care operations.”

Does giving methadone patient information to the EHR and the PDMP count? Would you consent?

Perhaps resistance to the general erosion of privacy protections is futile. After all, medical information of all kinds is already being given away and sold without patients’ consent or knowledge.

Methadone patients are uniquely vulnerable to nonconsensual disclosure of their health information.

Yet methadone, as the original Dear Colleague letter implied, should arguably be considered a special case. Society’s stigmatization of people who seek addiction treatment of any kind is at play; but methadone patients are disproportionately vulnerable.

This has much to do with the persisting stigmatization of methadone in particular. But socio-economic status—with methadone patients often poorer than those receiving buprenorphine, for example—is an important factor.

“The distribution of buprenorphine providers and the drift towards cash-only creates the [socio-economic] dichotomy,” said H. Westley Clark, MD, JD, former director of SAMHSA’s Center for Substance Abuse Treatment and now Dean’s Executive Professor at Santa Clara University. ”Of course, access to insurance also plays a role.”*

“If you are poor, uninsured, living in an area with few buprenorphine prescribers, living in a rural area, you are more likely not to be able to afford buprenorphine,” Clark told Filter. “If you are poor, and methadone is cheaper than buprenorphine, you are more likely to be on methadone. If you have Medicaid, then you are limited by Medicaid reimbursement and policies.”

Methadone patients, many of whom have previously been criminalized and treated badly by the medical profession, are therefore uniquely vulnerable to nonconsensual disclosure of their health information. The risks—or perceived risks—are dire, like losing their jobs, custody of their children, their assets, their freedom.

The Treatment Field Versus Patients

Clark authored that 2011 SAMHSA Dear Colleague letter which told OTPs not to enter patients’ data—along with the American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence ( an OTP trade organization), Faces and Voices of Recovery, the Legal Action Center, and Treatment Communities of America.

The American Medical Association (AMA) also supported keeping the protection. Its letter to Congress last fall helped to avert legislation which would have gutted 42 CFR Part 2. However, this spring the AMA House of Delegates voted to do away with it, in what the AMA calls “democracy” in action.

Almost all relevant trade organizations—including the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers (NAATP) and the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM)—also support the abolition of 42 CFR Part 2.

So do doctors, who want to look at their computer and see “methadone” on it, if a patient is taking it.

“We hear story after story of how patients will leave treatment prematurely if their right to determine who has access to their records is taken away.”

Patients, however, do not support this—especially methadone patients, who are virtually the only people left with meaningful protections under the current, stripped-down regulation.

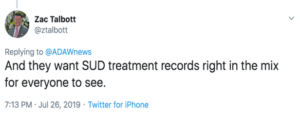

“Eliminating the consent requirement of 42 CFR Part 2 will directly impact the opioid crisis in a potentially catastrophic way,” said Zachary Talbott, an MAT advocate who attributes his own long-term recovery to methadone treatment, and is now director of clinical services for seven office-based opioid agonist treatment centers (OBOTs) in Tennessee and Virginia.

“In an online community of nearly 8,000 MAT patients from across the country, we hear story after story of how patients will leave treatment prematurely if their right to determine who has access to their records is taken away,” Talbott told Filter.

A Breakdown in Trust

Patients would rather be trusted to make their own decisions about disclosure—and trust is a two-way street. To agree to sharing of their methadone histories, patients need to be able to trust their doctor.

But with ASAM and NAATP broadcasting that they want agency removed from methadone patients, it’s hard to see how this will end well.

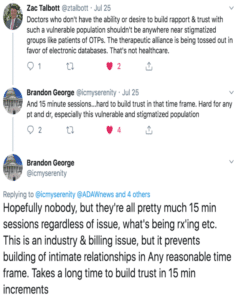

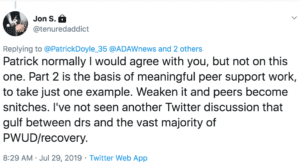

Half of the problem is that doctors generally don’t have the time, or sometimes the inclination, to build up the trust needed for patients to voluntarily disclose if they’re on methadone. So doctors want to just see it on their computer screen. This Twitter exchange sums it up:

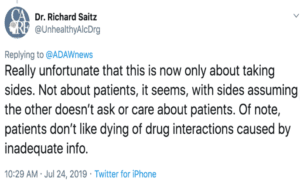

The other half of the problem is that doctors think there could be dangerous drug-drug interactions if they don’t know if a patient is taking methadone.

Yet when I asked doctors repeatedly for one example of this having happened, and why this wasn’t a problem before EHRs, they didn’t respond.

There can, however, be serious drug-drug interactions if a patient is using heroin or fentanyl, which will not show up on the PDMP or the EHR (until, that is, a doctor puts it there).

New York Leads the Way

State authorities aren’t generally addressing this problem. The National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors (NASADAD) said it can’t take a position because its members disagree.

But at least one state—New York—is committed to protecting patient consent to release information.

“In our relationship with our provider community—our goodwill with our provider community—we have taken it upon ourselves to develop consent forms,” said Robert Kent, longtime chief counsel to New York’s Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services (OASAS).

Providers know and follow 42 CFR Part 2, he told Filter. “Our providers are great. They know the law as well as we do, they religiously guard patient information, they tell their prospective patients that their information is protected by federal law.”

Noting that most treatment centers are not well financed—community organizations don’t have access to legal counsel in many cases—Kent said that OASAS makes itself available for advice, as well as having developed model consent forms that comply with 42 CFR Part 2. (Filter has posted a copy here.)

“Healthcare providers want to look at people’s SUD information without their permission. No matter how they dress it up, that’s what they want.”

Kent will look at the SAMHSA proposal when it comes out, but is doubtful whether it can remove the requirement for consent, which is codified in statute.

“I don’t know how you modify regulations that are supposed to be consistent with statute,” he said. Changing 42 CFR Part 2 to be like HIPAA means it would not include consent, which is required by federal law. Removal of consent, he believes, would need to be done by Congress.

“What’s really going on here is healthcare providers want to look at people’s SUD information without their permission,” said Kent. “No matter how they dress it up, that’s what they want. And our providers know what happens when this information is not protected.”

His main concern? “More people will avoid seeking treatment.”

When long-term methadone treatment cuts mortality for people with OUD by half or more, what are the likely consequences of this avoidance? If there was ever a situation where the interests of patients and treatment collided, this is it.

As Clark bluntly asks, “Why are the rights of patients being ignored?”

“Just Ask”

Joycelyn Woods, director of the National Alliance for Medication Assisted Recovery, recalled that Vincent P. Dole, Marie Nyswander, the doctors who first developed methadone as a treatment for OUD, would always emphasize: “Ask the patient.”

If the patient doesn’t tell you, “you need to examine yourself and what they used to call your ‘bedside manner,’” Woods told Filter. It’s vital to remember that just about every methadone patient—and every person who uses illicit drugs—has experienced “terrible behavior” from the medical profession.

“An experienced doctor should understand that,” she said. “More importantly, they should have the expertise to see problems about addiction in the patient’s record without removing 42 CFR Part 2.”

“Getting someone to agree to their information being given to others is an art, not a science.”

Like many proponents of 42 CFR Part 2, including notably Clark, Kent does not understand why doctors don’t “just ask” their patients what medications they are taking. And given the inaccuracy of many EMRs in terms of dose, spelling, medication, and so on, why wouldn’t you ask anyway? Patients will tell you—if they trust you.

Trust may be elusive, but, say Kent, Clark and many others, it is essential to a good therapeutic relationship.

“Getting someone to agree to their information being given to others is an art, not a science,” said Kent. “If you trust that your medical practitioner is truly trying to help you and cares about, you will tell them what they need to know.”

Kent noted that treatment for SUD is normally voluntary. The vast majority of people who want treatment don’t get it, due to many barriers. Why add another?

OASAS worked on a universal consent form for a purpose: getting buprenorphine inductions done in the emergency department. “We wanted the ED doctor to know the history, so we developed a consent form that programs could use,” Kent said. “As long as you’re telling the individual who would have access to it and for what purpose” it’s compliant with 42 CFR Part 2, he said. “At the end of the day, it’s a disclosure.”

Arguments for replacing 42 CFR Part 2 with HIPAA are often disingenuous—not focused on the well-being of impacted people—particularly when they come from people who don’t know much about addiction, like the AMA delegates.

“To be honest with you, the people who primarily advocate to default to HIPAA don’t really work with folks who have addiction issues,” said Kent. “I don’t think they understand, and they’re really focused on knowing this information for other things that they’re doing … I don’t think they understand that one of the dangers of doing this is that fewer people will get treatment” for OUD.

Doctors Push Back—And Patient Advocates Are Afraid

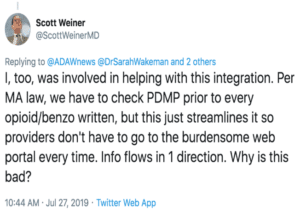

Few states offer New York’s protections. In Massachusetts, there is an agreement for all patient information to flow from the PDMP to the EHR so that physicians don’t have to check the PDMP. Methadone wouldn’t be on the PDMP—unless SAMHSA’s Dear Colleague letter is rescinded. That, of course, could happen.

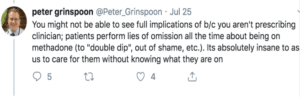

Peter Grinspoon, MD, a progressive primary care physician who was himself previously addicted to opioids and supports cannabis availability for OUD patients, works at Massachusetts General Hospital. He says he knows from personal experience that taking patients’ word about whether they’re on methadone isn’t safe, given many potential reasons for non-disclosure.

Many doctors, like Grinspoon, would prefer to find this information on the EHR. Doctor-patient trust, they believe, is desirable but not always attainable, even given time and effort. (Even though many doctors rely on patient disclosure about other medications they are taking, how much alcohol they drink, and whether they smoke or vape.)

The Twitter exchange below, between some top addiction physicians in Massachusetts, reflects doctors’ concerns about the burden of checking the PDMP, and the widespread preference for one-stop shopping on the EHR.

For many doctors, removing 42 CFR Part 2 is all about creating a registry, including methadone, said Clark. Law enforcement is interested in this as well.

The rationale is convenience and safety. But bear in mind, too, that these records are valuable—just as Facebook information is for sale, medical information can be sold and re-sold.

And the consequences of abolishing 42 CFR Part 2, given the widespread threat of patients leaving treatment that Zachary Talbott reports, could be disastrous.

“We know that leaving treatment absent a proper taper and solid discharge plan most always means relapse,” said Talbott, who has opened and operated OTPs in multiple states. “We know that relapse often can mean overdose and death. NAMA Recovery heard from a multitude of prospective patients and their family and friends last year who were considering enrolling in MAT but were dissuaded by the reality their treatment might not be fully protected.”

“There is evidence of law enforcement targeting patients and treatment centers across the country.”

“There is simply no objective evidence,” he continued, “that the last half century of 42 CFR Part 2’s existence alongside opioid treatment programs and other SUD treatment programs has led to any of the drug-drug dangers or poor patient care that proponents of removing the consent requirement continue to espouse. There is, however, a multitude of evidence that stigma against SUDs in general and MAT in particular permeates the medical community.”

“There is evidence,” he added, “of law enforcement targeting patients and treatment centers across the country—and HIPAA alone provides zero protections against law enforcement accessing information if the consent requirement is removed.”

“The reality is that stigma is a powerful and deadly force, and individuals with substance use disorders are still criminalized across the country. Until this ends, we must do everything we can to preserve the core confidentiality protections of 42 CFR Part 2. Lives could quite literally depend on it.”

*See “Buprenorphine Treatment Divide by Race/Ethnicity and Payment,” by Lagisetty, PA, Ross R, Bohert A, Clay M and Maust, DT, JAMA Psychiatry, Published online May 8, 2019 and “Proliferation of CAsh-Only Buprenorphine Treatment Clinics: A Threat to the Nation’s Response to the Opioid Crisis, Van Zee, A, Fiellin, DA, American Journal of Public Health, March 2019, Vol. 103, No. 3, pages 393-394.

See also “Risk factors for discontinuation of buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorders in a multi-state sample of Medicaid enrollees”, Samples, H; Williams, AR, Olfson, M, and Crystal, S. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 95 (2018) 9-17.

Photo by Ahmed Hasan on Unsplash

Show Comments

Dee

Thank you for this article. I am just seeing this. For people who were cut off their pain medications and chose to find a methadone clinic, this will be a disaster.