Like much of the nation, Philadelphia has come to a virtual standstill. At publication time, Philadelphia County had almost 6,400 confirmed coronavirus infections and 176 reported deaths. In a city with a pre-existing poverty rate of 24.5 percent, the economic damage of the lockdown is palpable. Businesses that were Philly fixtures for decades are now boarded up—some may never open again.

It has been distressing to witness the additional strife within the community I cover, the most vulnerable of Philadelphia’s populations of people who use drugs.

Despite widespread fears of a drought, trade in illicit drugs in the Kensington neighborhood has so far continued at a steady pace. “You look around the city and it’s like there’s nobody out,” a corner dealer told me. “But not Kensington.”

“Look around you,” he said, gesturing to the crowded street corners. “If you out here, you either buyin’ drugs or you sellin’ them.”

For a reporter who has been on this beat for years, one odd impact of the pandemic has been the instant clarification of who’s buying and who’s selling: The former are usually wearing medical masks, the latter usually not.

But amid the brisk business, tenuous supply lines seem to have led to a significant decline in the potency of many of the drugs available. Heroin users, for example, rate the drug on its “rush”—the initial impact of the drug—and its “legs,” or length of time before withdrawal sets in. Sources report a decline in both.

In one way, it’s a good thing: Fatal overdoses in the city have declined from an average in the region of three or four per day to something more like three or four per week, according to daily tallies released by police, EMTs and Prevention Point Philadelphia, a needle exchange program.

But the decline in potency hasn’t come without consequences. Illicit markets work best—in terms of both product safety and violence reduction—when they are free to operate organically. Under the pressure of uncertainty, fear or desperation, the cracks in Kensington’s already-troubled community are showing.

An Uptick in Violence

Visible violence between people who use drugs has increased dramatically over the past three weeks. I’ve seen people punched and knocked to the ground for no apparent reason along the main strip of Kensington Avenue, and witnessed cellphones ripped from owners’ hands just as the subway door opens.

A disagreement over money or drugs may be the spark in some cases, but the general tension that comes from diminished prospects and mounting hopelessness surely contributes.

Despite dramatic falls in recorded crime rates across the US and the world, thought to be a result of lockdowns, Philadelphia’s homicide rate is up by double digits over last year.

Not all killings, of course, are related to the illicit drug market, but some are. Many acts of violence seem random. On March 30, Nicholas Troxell, a heroin user well known by many in the Kensington community, was shot and killed on an El train passing through North Philly. That same week the attempted robbery of a man selling pills further south, in the Fishtown section of the city, ended with three people wounded by gunfire.

The decline in product purity has kept many opioid-dependent Philadelphians in a state of near constant fear and anxiety, which is not a good combination in Kensington.

“I guess they didn’t like that he was passing them and buying from somewhere else.”

One long-established source of mine, who uses heroin and crack cocaine, described watching a man he knows get pummeled by members of a drug dealing “set”—allegedly for just passing by their corner without making a purchase.

“If you got garbage on the street, no one is gonna buy your stamp; we have to make our money stretch as much as possible,” this source told me. “I guess they didn’t like that he was passing them and buying from somewhere else. Maybe he was a regular customer.”

There was a time in Kensington when the culprits of such senseless violence would probably have been disciplined, perhaps by being banned from working the block altogether. But aggressive drug policy, by targeting and removing gang leadership, erodes the structures that support such codes of conduct. It’s one of the ways that prohibition increases violence.

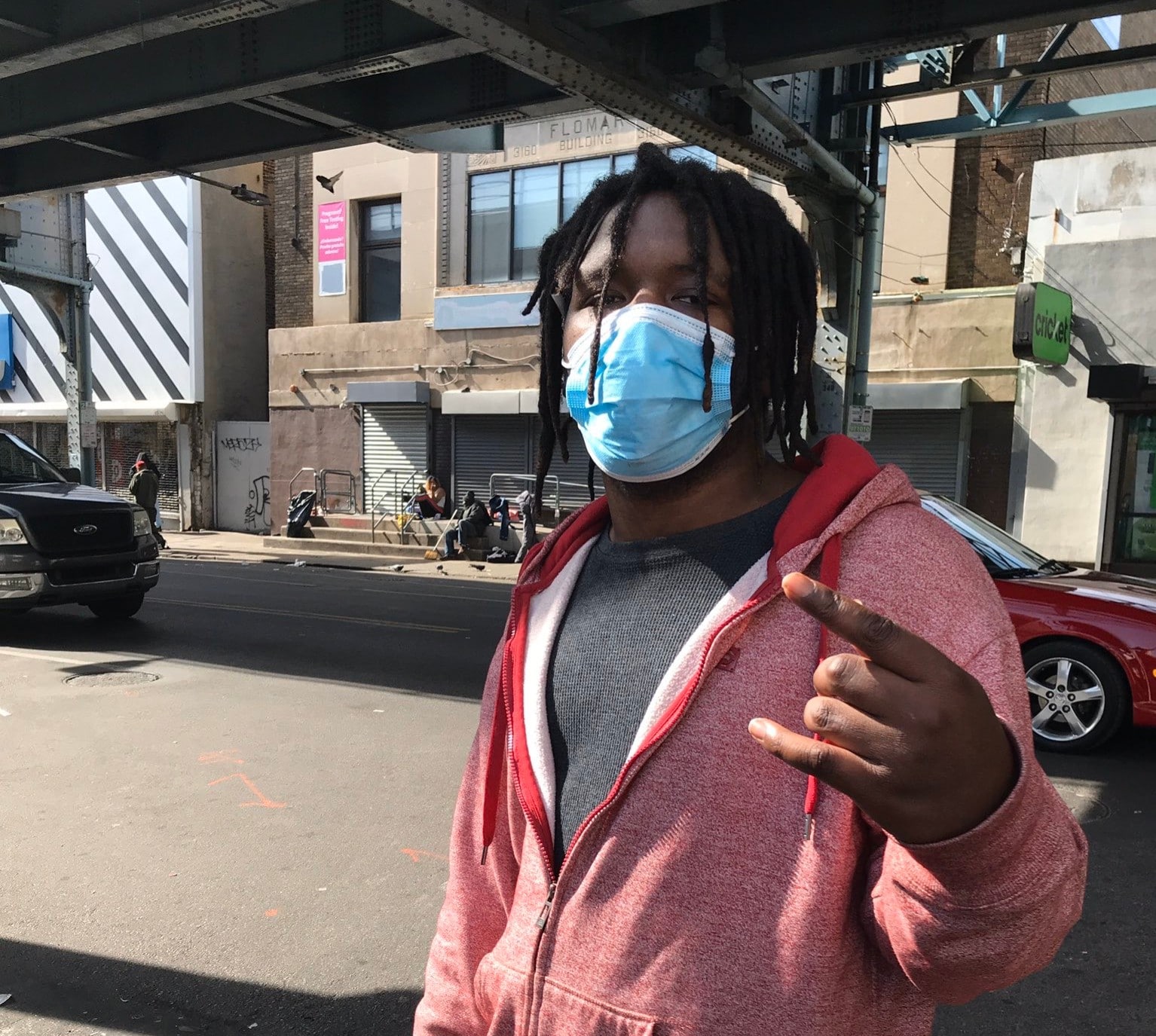

[Update, April 15: A few hours after this article was published, a man called Mike, who has been a source or fixer of mine in Kensington since 2017, was attacked at Philadelphia’s City Hall station—apparently for money, although he had none. His attacker simply asked, “What are you looking at?” before jumping on him. Mike suffered a broken rib among other injuries. The photograph below, taken shortly afterwards, is shared with his permission.]

Drug Shortages Due to Fear Itself?

Illicit drugs—albeit in less-potent form—are still plentiful in Kensington. But with traffic across the US-Mexico border now limited to “essential services,” there is a perception, at least, that it will become harder to get drugs like fentanyl and heroin to East Coast markets.

Scott Stewart, a cartels expert with the geopolitical intelligence publisher Stratfor, told Filter that the flow of illicit drugs across the border has not visibly slowed.

“I wonder if street dealers are buying that hype and cutting their product out of fear.”

“Most of the tractor trailers and trains are still crossing the border [for purposes deemed essential], and we know the cartels are pretty good at hiding stuff in the midst of that commercial traffic,” he said.

He speculated that local drug supply issues may be produced by the fear of a shortage, rather than a shortage in absolute terms. “I wonder if street dealers are buying that hype and cutting their product out of fear of a supply cut.”

In Kensington, people who use heroin/fentanyl and cocaine have experienced a recent decline in quality. But methamphetamine remains abundantly available at pre-pandemic purity levels, my sources say. Stewart said he’s heard that there is so much surplus meth on the market that the cartels are “sitting on it” until prices rebound.

The diluted opioid supply subjects people who rely on it to additional pressures. One man told me last week that it was taking him twice his normal dose to get well. A couple of days after we spoke, he injected himself in a public bathroom in Kensington, and subsequently collapsed in the parking lot outside.

He awoke, surrounded by paramedics. But he was not given naloxone, because whatever it was that knocked him out briefly, it wasn’t an opioid. (My guess would be xylazine, a large-animal tranquilizer that is present in most of Kensington’s dope supply.)

In a show of good faith, most of Philly’s methadone clinics have been giving the maximum allowable number of take-home doses to clients under state law (one week), even those who wouldn’t normally qualify. But one clinic doctor, who asked that he not be identified due to his employer’s restrictions on talking to the media, told Filter that there is a virtual moratorium on new intakes.

Vanished Incomes, Safe Spaces

In addition to any drug supply issues, many of the most marginalized drug users have seen their fragile incomes disappear. With so many streets in the wider city empty, panhandling has become fruitless. Clientele for casual work, like window washing, have dried up. Sex work has been curtailed. Some of my regular sources have recently phoned me in tears, begging for any small financial help I can offer. I oblige whenever I can; when I can’t, I feel hollow.

Others have found some limited opportunities in the new reality. After Philadelphia’s Police Commissioner, Danielle Outlaw, announced in mid-March that her officers would no longer bring in nonviolent offenders for booking, but rather issue a summons to appear in court, the subways and trains became moving bazaars for stolen goods.

We’re not talking high-end merchandise. On a single day just over a week ago, I was offered disposable razors of every brand imaginable, USB chargers and bags of candy—all at cut-rate prices.

“The hardest hit from this crisis will be the most vulnerable populations.”

The Southeastern Pennsylvania Transit Authority (SEPTA) has lately come under fire for its decision to shutter a number of stations—part of massive cutbacks following a drop in ridership of over 80 percent. (SEPTA had already temporarily curtailed its 24-hour train service, which for years has served as a last resort shelter for homeless people.)

Two of those stations, Somerset and Tioga, are in the heart of Kensington. Somerset, in particular, has been a de facto safe zone for transient drug users, and a conduit to numerous drug corners within a two-block radius of the station.

Vince, who is from New Jersey but has been homeless in Kensington since the winter of 2018. Photo by Seth Dalton.

Jamie Moffett, a neighborhood organizer and philanthropist, phoned me when news broke of the closures. “I’m concerned [that] closing these stops will concentrate vulnerable folks with pre-existing conditions and no ability to purchase masks or personal protective equipment to the Allegheny stop on Kensington Avenue,” he told me.

Kensington and Allegheny—”K&A”—is already a primary gathering spot for people who are homeless and addicted. “The potential for a ‘super spreader’ coronavirus event at K&A would be deadly,” Moffett said, “especially to folks who can’t shelter in place, as they have nowhere safe to shelter.”

“The downsizing decisions were really tough,” Thomas Nestel, chief of the SEPTA Transit Police, told Filter. “The Authority is in dire financial status, losing employees every day. I hope this crisis lets people know just how many unsheltered use SEPTA as their home.”

“When this is over,” he continued, “I believe the hardest hit from this crisis will be the most vulnerable populations—the drug addicted, the homeless, the mentally ill.”

Nestel’s agency, which has jurisdiction not only in Philadelphia but five of its surrounding counties, has seen some of the worst local impacts of both the overdose and coronavirus crises. In recent times, overdose incidents on SEPTA’s train, trolley or bus lines have occurred daily.

Nestel notably declined any new officers when the City Council offered them to him last year as a response to other police departments’ shutting down nearby encampments. He requested that 10 social workers be hired for him to deploy instead. That program was approved, but has been put on hold due to COVID-19.

A Lesson for Drug Warriors?

What hasn’t been put on hold is the suffering of Philadelphia and Kensington’s most vulnerable.

This past week, filmmaker Seth Dalton and I were forced to take an indefinite hiatus from filming a documentary we’ve been making about addiction, failed drug policy and the fight for safe consumption spaces in Philadelphia.

I’ve reported from these streets for years, through every kind of crisis. But our obligations to protect others in our lives from the virus have made the streets and subways too unpredictable right now.

There is only one time I can remember seeing it this bad—and unlike COVID-19, it was a political creation. It was in 1998, when I was a young heroin user myself, and then-Mayor John Street launched Operation Sunrise—a saturation offensive that flooded Kensington with police 24/7.

In the year that followed, I had a gun pointed at my head by a nervous teen robber, I was arrested twice, and I fought off another drug user who on two separate occasions tried to steal my drugs as I walked to the train. He failed, but the man who broke my jaw with one punch later that year didn’t.

If there is a lesson in the COVID-19 crisis for drug warriors, it’s this: Even adding a deadly pandemic to the existing threats of overdose and law enforcement will not end drug use. Nothing will. We need approaches that focus solely on reducing the suffering we see all around us.

Top photo, showing a man in a mask outside the Allegheny train station, Kensington in mid-March, by Christopher Moraff.

Show Comments