Idris Azizi speaks softly when he relates how, as a person living with HIV, he was told to sit in the trunk of a car, with the door open, when traveling to a 2017 Global Fund committee meeting in Kabul, Afghanistan. The two doctors from the Ministry of Public Health with whom he was traveling sat in the car cabin.

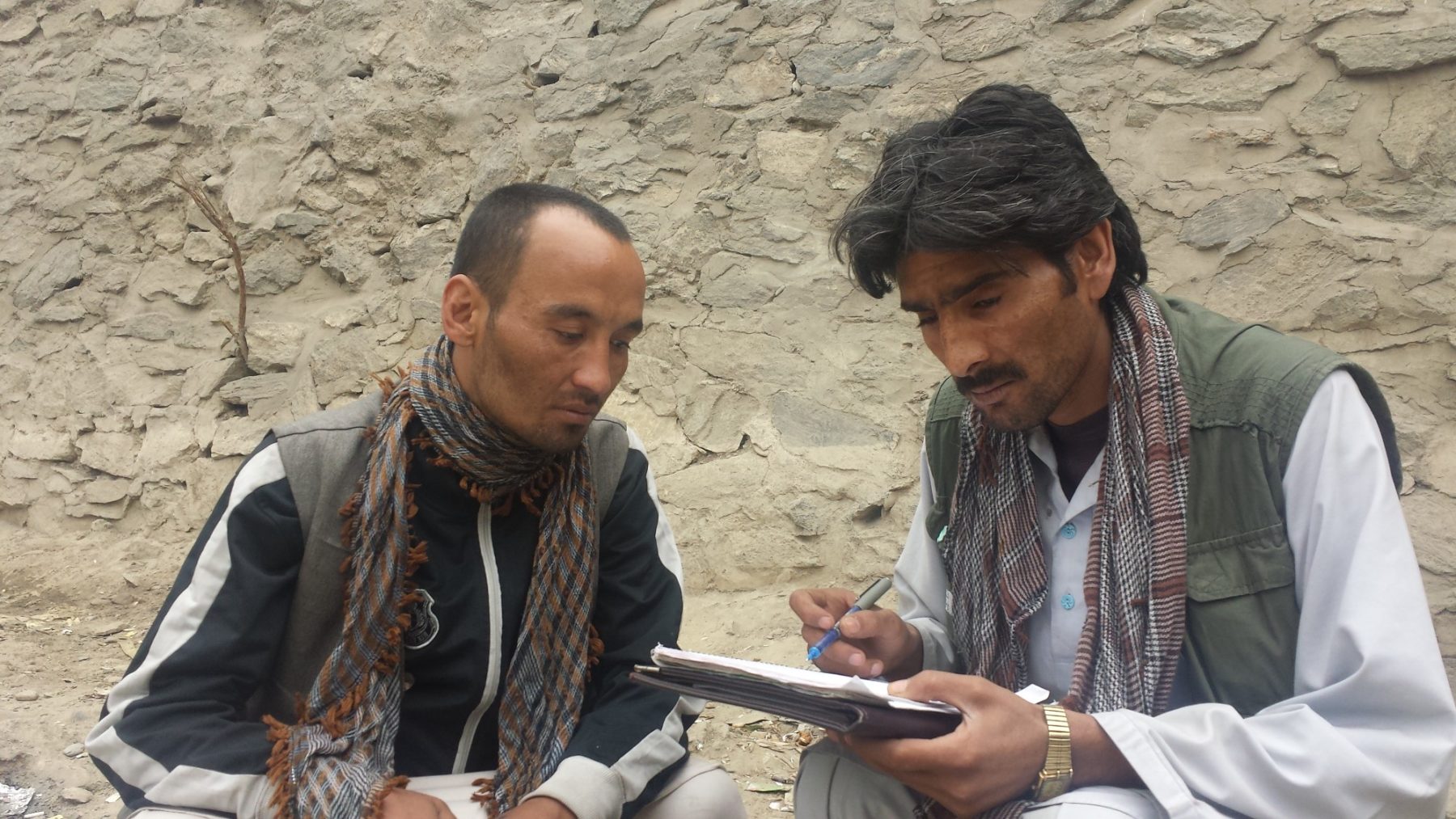

“The [committee] members were not comfortable with me—these were doctors,” Azizi (pictured above, right) told Filter. “When they were going to the oversight meeting, they did not tell me. They didn’t share the schedule, the meals, the car,” he said, referring also to the per diems that cover costs during official meetings. “And the one time that they did share the car, they put me the trunk.”

With his easy-going demeanor, he could easily be talking about an unfortunate misunderstanding. But Azizi is an official spokesperson for PLHIV, or People Living with HIV, and paid a monthly stipend of 10,160 AFN a month ($129) through Afghanistan’s Global Fund. He speaks on behalf of Afghans who do not feel safe disclosing their HIV status.

The Global Fund, which was set up by the United Nations, describes itself as an organization dedicated to fighting AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria, all of which are present in Afghanistan. To ensure that people directly impacted by these diseases have a say in how resources are used within their countries, the Fund set up the Country Coordinating Mechanism (CCM), with an oversight committee made up of community members, like Azizi, as well as technical experts, such as the doctors who shunned him.

“Prolonged exposure [to violence], instability, and a lack of security causes people to find other coping mechanisms to survive.”

Afghanistan struggles with insecurity, ongoing war, poverty and one of the highest unemployment rates in the world. In a country where the poppy harvest produces more than 90 percent of the world’s illicit heroin, despite the US military’s failed efforts to prevent this, opiates have provided solace to populations affected by mental traumas or physical health issues. People use them to manage stress and physical pain. But visible use can lead to people being pushed from society.

“From my experience, prolonged exposure [to violence], instability, and a lack of security causes people to find other coping mechanisms to survive [including opiates],” said Lyla Schwartz, a psychologist and program director for Peace of Mind of Afghanistan (PoMA), an organization dedicated to destigmatizing mental health issues in Afghanistan. “Culturally speaking, after the community or family system becomes aware of this, it is an exclusion factor which usually leads to ‘being removed’ from that system.”

Azizi began smoking opiates while he was a migrant worker in Iran. He and his friends then chose to begin injecting because “we didn’t have enough between us and injecting was the economical solution.” A person must smoke 5 grams of opiates to get the same effect as injecting 0.5 grams, but injecting carries added health risks.

“We didn’t know that sharing needles led to HIV,” he said.

According to the Global Fund, the rate of HIV in Afghanistan’s general population is about 0.05 percent. The highest rates are found among injecting drug users, estimated to be as high as 4.4 percent, and the people termed “men and women with high risk behavior,” which includes sexual behaviors.

Antiretroviral treatment in became available in Afghanistan in April 2009. The first cohort of methadone treatment started in 2008. Azizi was in that cohort, and says harm reduction changed his life.

Now he has a wife and five-year-old son, and works as a peer educator in Kabul, a job that he loves. As harm reduction advocate, he can now educate others on the importance of clean needles. But the stigma he has faced even from health professionals sheds a harsh light on the obstacles to harm reduction in this country.

Exclusion From the Public Health Community

Raheem Rejaey was also in that first cohort of methadone treatment—a pilot project for 71 patients facilitated by Medicine du Monde, or MdM. In fact, he was the very first participant.

He now represents civil society on the CCM. In 2015 he founded Bridge Better Hope Health Organization, a national non-governmental organization registered with the Ministry of Economy. Launched initially as a volunteer-based program in Kabul, Bridge received its first international grant in 2016 to train a cohort of peer educators, including Azizi, in first aid care, human rights support and how to help Afghan drug users access harm reduction.

Rejaey’s harm reduction work has been a realization of a dream, as he too once struggled with homelessness and problematic drug use. “MdM got me healthy, so I wanted to use my life to help others,” he told Filter.

But despite his impressive CV, having worked in harm reduction since 2008, Rejaey said he was “banned” from CCM membership in 2018—for speaking out against the doctors who forced Azizi to sit in the car trunk.

After communications with Global Fund leadership, apologies were issued in private and both Rejaey and Azizi were invited back this year to attend meetings. The two doctors involved were removed from the oversight committee. But change has been slow.

Peer Work and Psycho-social Support

Afghanistan’s harm reduction workers face many challenges, but naloxone provision has been a positive force for the community. People who have undergone detoxing and abstinence from heroin, or “cold turkey,” are at heightened risk for overdose if they use again, and naxolone counteracts this.

“We [would] watch people overdose and die after getting out of detox, because they use the same dose, but their bodies can’t handle it,” said Rejaey.

Previously, naxolone was not available to Bridge, and the NGOs that did have access did not conduct outreach visits to people using in homeless encampments.

“They don’t go to the bridge [in Kabul, under which many homeless people live] to help people. An overdosing person can’t come to [to an NGO],” Rejaey explained.

“With naloxone, we have been able to save over 50 lives,” said Ata Hamid, Bridge’s project coordinator, “but before that there were people who passed away.”

Bridge peer workers are well aware of the dangers of detoxing; most found methadone treatment the only way to break free from addiction. But being part of a community and finding a purpose has played a role as well.

“We have no psychologists, but we have canaries on the compound.”

Bridge has a community garden for its peer workers, with carrots, peppers, eggplant, potatoes, mint, radishes, onions, cucumbers, pears and roses growing. The small compound provides a form of solace in place of formal psycho-social services. “We have no psychologists,” said Rejaey, referring to the garden, “but we have canaries on the compound.”

Raheem Rejaey administering wound care in Kabul. Photo courtesy of Bridge Better Hope Health Organization.

Schwartz from Peace of Mind Afghanistan says rebuilding a sense of community and sponsorship is a key part of why self-help groups are successful. “I cannot express enough how much that makes a difference,” she told Filter. “[Also] providing a purpose, skills trainings and job opportunities” can help with the healing process.

“Peer educators like working with Bridge because we trust them to do their work,” said Hamid. “I tell them meeting our outreach targets is the most important part of our work,” which means getting services to drug users out in the community.

During the organization’s launch in 2016, the peer workers were trained in how to conduct outreach visits, educating drug users on harm reduction methods, overdose management, and providing wound care and first aid services. Madawa, a harm reduction organization, trained the peer workers in advocacy, while Mat Southwell and Buff Cameron, both technical advisors from CoAct, trained them in overdose management and security awareness.

Bridge has been supported by micro-grants from donors such as Madawa and UNDP. Despite the limited funding, its leadership of former and current drug users and its peer workers know how important their work is.

In its first year, Bridge’s peer workers “mapped” 1,969 drug users in Kabul (1,835 male and 109 female), of whom 1,895 were identified as homeless. Bridge has now served more than 2,000 people who use drugs, and provided over 1,250 people with wound care, according to Hamid and Rejaey.

In 2017, Bridge also started working with women, under grants supporting “women with high risk behaviors.” Its trained women outreach workers have so far provided 1,573 women with harm reduction services and another 1,373 women with testing services.

“The police started beating me—first one and then another—then they brought me to the police station.”

Bridge currently has five social workers and eight peer workers. They use a van for outreach trips and travel together for safety. “It is better that there are two or three working together and carrying ID cards,” said Rejaey, and there is good reason for this.

Azizi once visited the community by himself and was beaten by the police. “The police started beating me—first one and then another—then they brought me to the police station,” he said. Hamid came to get him and explain that he is an outreach worker.

But the dangers of this work can be even more acute. One Bridge peer worker, Naser Khalile, always had a ready smile for visitors to the compound.

Naser Khalile. Photo courtesy of Bridge Better Hope Health Organization.

On August 28, Khalile was killed by thieves for his motorcycle while he commuted home after peer work. He had been safe with his colleagues that day, but all Afghans face grave security risks just going about their lives.

Bridge peer workers holding certificates of training completion with staff in 2016, including Naser Khalile (kneeling, in white) and Raheem Rejaey (standing center with hands folded). Photo by Michelle Tolson.

Bridge peer workers holding certificates of training completion with staff in 2016, including Naser Khalile (kneeling, in white) and Raheem Rejaey (standing center with hands folded). Photo by Michelle Tolson.

Fighting for Health Access

While antiretroviral therapy reduces the presence of the virus in the blood and risk of transmission, people who test positive for HIV face significant obstacles to health treatment, which is one of the reasons advocacy is so important. People who test positive for hepatitis can similarly be blocked from medical treatment. Azizi’s friend died of appendicitis in 2016, after doctors refused to operate because of his HIV status.

In October 2016 during Bridge’s first peer educator training, one trainee, a homeless Afghan drug user named Haji who managed to attend almost every training session, could not find healthcare to save his life.

I reported on the training and met Haji, who sometimes nodded off to sleep during the classes (said to be a side effect of methadone, which he was taking). One day, Haji stopped showing up to the course.

Haji expressed intense fear that he would die; he knew that doctors wouldn’t want to treat him as he was HIV-positive.

Rejaey learned from other peer educators that Haji had appendicitis. They found him sick under the Pul-e-Sokhta bridge in western Kabul, a well-known site for homeless drug users to congregate and live. Haji expressed intense fear that he would die; he knew that doctors wouldn’t want to treat him as he was HIV-positive. Rejaey then reached out to an influential person at the Ministry of Public Health, who called the clinic where Haji was brought and ordered it to operate on him.

The next morning, other peer educators said Haji’s body had been found under the Pul-e-Sokhta bridge. Rejaey and his team believe that the clinic dumped him back at the bridge, where he died.

“He was taking antiretroviral, so the virus count was low in his body, but they still refused to treat him,” said Rejaey. Bridge supporters made a controversial video with graphic imagery of others left for dead under the bridge, to bring attention to this senseless death.

Then in October 2018, Rejaey, who has hepatitis, also fell ill with appendicitis, but friends were able to organize treatment at a private clinic in Kabul. The Afghan operating physician, who spoke to media about this issue, used disposable surgery equipment and gowns designed to treat patients with hepatitis or HIV.

Naweed Hamkar, a young Afghan doctor who has worked in government hospitals in both Kabul and Ghazni, agrees that disposable equipment is an option, if available, but feels that the lack of resources and liability concerns are the real issues.

“The reason why most of the doctors don’t want to operate on HIV-positive, hepatitis or HCV patients is the lack of [proper] materials in the operating room,” said Hamkar, citing protective eye covering and other disposable equipment. He had to rely on his own glasses to protect his eyes. He told Filter that government hospitals do not have the resources to purchase these for patients, nor do poor patients. Private hospitals do, as was the case with Raheem, but the patient must pay for this.

Protecting other patients from potential infection is also major concern when the liability is on the doctor. “A doctor’s salary in Afghanistan during [his/her] residency is not more than a $100 [a month],” said Hamkar, “so, first the doctors don’t want to risk their career, and secondly, in Afghanistan doctors are not insured. There is no insurance policy, so both doctors and clinics don’t want to [take] the risk.”

Medical tourism is common for those that can afford to leave the country, as families will travel to Pakistan or India to get treatment for their families. But the population that Bridge advocates for does not have these options.

The severity of all of these challenges is what makes the work of the Bridge team so essential. They continue to inspire all who come into contact with them, and their efforts do not go unnoticed. Rejaey recently received the Carol and Travis Jenkins Award from Harm Reduction International for his outstanding work.

Raheem Rejaey at Bridge’s launch in 2016. Photo by Michelle Tolson.

Top photo of Idris Azizi conducting an outreach visit in Kabul courtesy of Bridge Better Hope Health Organization.

Show Comments