Kansas, one of the last two states without a “Good Samaritan” law for drug overdose, is poised to enact one. House Bill 2487 advanced to the Senate on February 22, where it is reportedly expected to pass. On paper, this would leave Wyoming as the only state that doesn’t encourage people to call emergency medical services at the scene of an OD by promising them legal immunity. In practice, while all these laws vary hugely from one state to the next, none of them are really designed to protect the people who most need legal immunity.

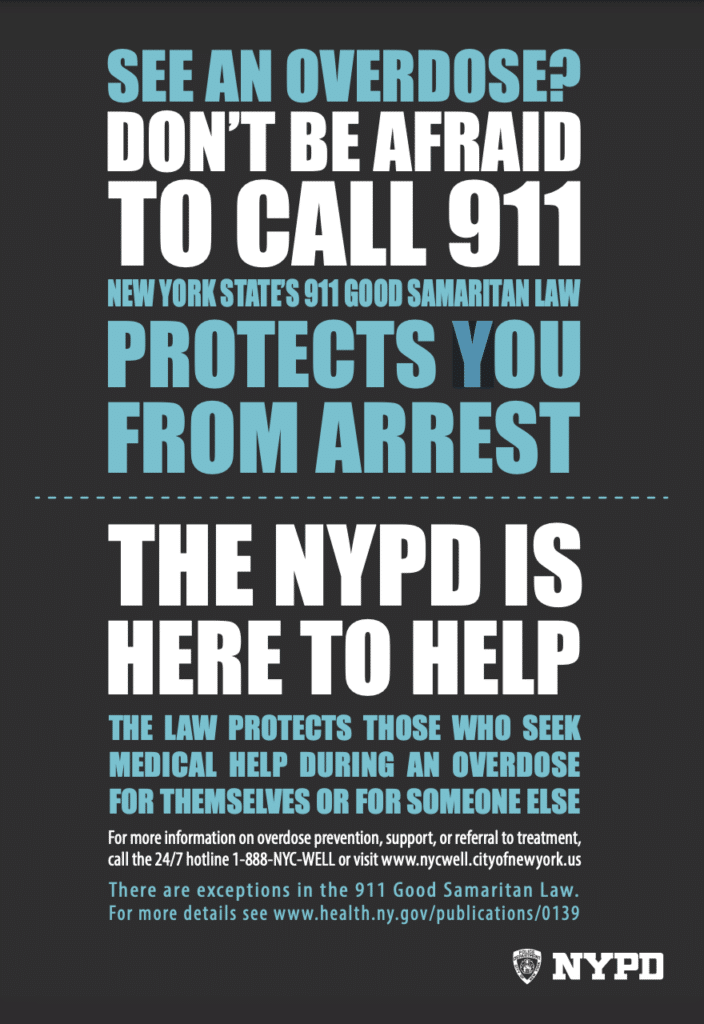

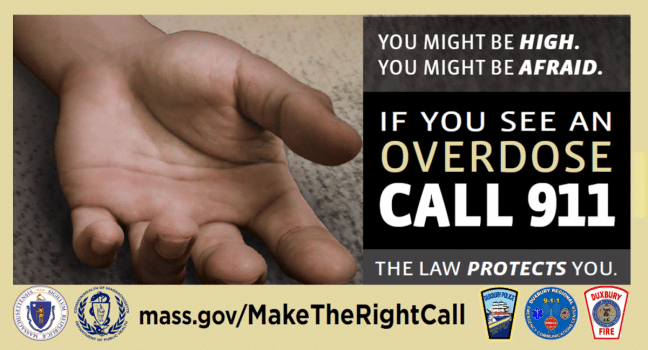

The rationale behind Good Samaritan laws is that people aren’t necessarily afraid of paramedics, but of the cops who tend to show up along with them. By assuring anyone who calls 911 that they won’t be prosecuted for having drugs on them, or for being high, they’ll be less likely to flee the scene without rendering aid. In theory, everyone’s safer.

State public awareness campaigns will make sweeping statements about how the law protects you—you—when you call 911, then make some reference to the fine print. If you are in possession of too much drugs; in possession of pipes or syringes; sell drugs; share drugs; have prior drug convictions; have open warrants; are on parole; have OD’d before; or have called for help before, then the law probably protects people who are not you.

Many Good Samaritan laws grant immunity for possession, but few for sale or sharing. Nine states have laws that lack any protections related to “paraphernalia.” Only seven include anything about civil asset forfeiture.

In West Virginia, immunity for the person who OD’d is contingent on completion of a drug court program. Ohio requires both the person who OD’d and the person who called 911 to get a referral to addiction treatment within 30 days, and to produce documentation showing they’ve completed it if the prosecuting attorney requests it.

In many states, the person who called 911 is required to use their full legal name, stay at the scene and provide their contact info; Alaska requires they show ID. If they don’t “fully cooperate,” they don’t get immunity and neither does the person who OD’d.

Of the 48 states with Good Samaritan laws on the books, eight don’t extend any immunity to people who OD using opioids.

Alabama, Indiana, Oklahoma and Wisconsin only grant immunity to the person who called 911, not the person they called about. Alaska, Arkansas, Maryland and South Dakota extend it to people who seek help on their own behalf, but someone OD’ing from opioids (or other banned substances with sedative effects) can’t call 911 on themselves, any more than they can Narcan themselves. They are unconscious.

Texas won’t grant immunity to anyone who’s been involved in a documented OD in the past 18 months.

In Tennessee and Iowa, the law doesn’t apply to the person who OD’d if records show they’ve OD’d before; Iowa extends this to the person who sought help, too. Ohio will grant immunity to the same person twice, but not a third time.

Texas, which was the third remaining state without a Good Samaritan law before enacting a messy one in 2021, won’t grant immunity to anyone who’s been involved in a documented OD in the past 18 months. Or to anyone with prior drug convictions.

In South Carolina, if the person who called 911 or otherwise sought help has sought help for others in the past, immunity from prosecution hinges on how the court views “the circumstances of the prior incidents and the related offenses.”

Good Samaritan laws sometimes protect eligible parties from being charged with drug possession. But in many states, the law only protects people from being prosecuted—not from being arrested.

In the original version of HB 2487, Kansas would have extended immunity to up to four people who call 911 or otherwise report an active OD to emergency medical services, in addition to the person who OD’d. The version headed to the Senate pared that back to one, and also removed a portion that would have protected people from punishment for violating terms of parole or probation.

Good Samaritan laws aren’t written to protect people who use the most stigmatized drugs every day, or who use them in stigmatized ways.

If passed, Kansas will be one of 22 states with a Good Samaritan law that protects people who’d otherwise face prison time for drug possession—but offers no immunity for those facing prison time because they’re under some form of community supervision like parole, probation or pretrial release.

New Jersey’s law states that e.g. parole shouldn’t be revoked as a result of seeking or obtaining help, but it may call for “establishing or modifying the conditions of parole or probation supervision.” Maryland’s law excludes the person who OD’d, assuming they didn’t call on their own behalf. Lawmakers want to make sure no one ends up with criminal charges because they tried to save a life—except for the people they can send back to prison without any new charges being filed to begin with.

Good Samaritan laws aren’t written to protect people who use the most stigmatized drugs every day, or who use them in stigmatized ways. Mostly they’re written for people with no involvement in the criminal-legal system. They encourage everyone involved in an OD to call for help, and only make it safe for some of them.

Top image via Office of Nevada Attorney General. Second image via City of New York. Third image via Town of Fairhaven, Massachusetts.

Show Comments