Documents obtained by Filter provide insight into how the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) originally intended to handle an avalanche of incoming premarket tobacco product applications (PMTA) for open-system vapes.

Open-system vaping products, which remain popular among consumers and many of the most vocal tobacco harm reduction advocates, have a tank that’s manually refilled with e-liquid. Past research has suggested that around half of vapers use them, and they are rarely—if ever—associated with youth use. Most vapers, of course, are former smokers who have switched to a safer way of consuming nicotine or current smokers seeking to do so—which makes FDA decisions over access to their preferred products a pressing matter of public health. That’s particularly true for open systems, which tend to have a wider variety of the flavor options adults like.

Essentially, CTP seems to have imagined a couple of years ago that an expedited process would efficiently produce large numbers of marketing denials and authorizations for open-system vapes and e-liquids. That proved over-optimistic. And despite imposing extremely onerous bureaucratic requirements on applicants, the agency was happy to find ways to cut through its own paperwork.

A jargon-filled memorandum from August 19, 2020—titled “Bundling and Bracketing Approach for Review of ENDS [Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems] Open E-liquid PMTAs,” and signed by CTP’s former Office of Science Director Matthew Holman—outlines much of the initial plan. (Filter received the memo, which you can view below, through a FOIA request.)

“FDA anticipates that a substantial portion of PMTA ENDS submissions during the compliance period will consist of open e-liquids that contain hundreds to thousands of products with variations in CF [characterizing flavor], nicotine concentration, and PG:VG [propylene glycol and vegetable glycerin] ratio based on the tobacco ingredient listing submitted by tobacco product manufacturers and importers,” the memo reads. “To increase the likelihood that more tobacco products will be reviewed and receive marketing orders before the end of the compliance period, the Office of Science (OS) is implementing a bundling-bracketing review approach for ENDs open e-liquids PMTAs.”

One attorney who’s currently litigating appeals told Filter that they are “currently evaluating whether or not the [August 19] memo should have been included in the administrative record.”

The FDA did not respond to Filter’s request for comment by publication time, to confirm whether the bundling-bracketing approach remained in place.

The FDA didn’t end up following its initial strategy: By July 2021, the agency had resorted to a far more sweeping process, the so-called “Fatal Flaw” standard.

As acknowledged in the August 19 memo, vapor manufacturers had until September 9, 2020 to submit their PMTAs to the FDA following a decision by the United States District Court for the District of Maryland. (Prohibition-minded lobbying groups, including the Michael Bloomberg-funded Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, had sued the FDA to move up the deadline.) The agency, in turn, was expected to basically review the applications within a one-year “compliance” period, and had signaled that it would prioritize the companies with the largest market share first. What CTP had to consider, in short, was if an application met an “appropriate for the protection of public health” (APPH) threshold—meaning the given product would be more likely to help adult smokers transition to a safer alternative than introduce a new generation to nicotine.

It’s clear that the FDA didn’t end up following its initial strategy: By July 2021, the agency had resorted to a far more sweeping process, the so-called “Fatal Flaw” standard. This targeted the top 12 manufacturers with the largest number of pending PMTAs not in scientific review—at the time, 85 percent of all pending applications—and rejected them at a stroke if they did not include two types of extensive studies.

That move, which triggered countless marketing denial orders (MDOs) and, consequently, dozens of lawsuits in district appeals courts, came not long after Congress had lambasted then-FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock for not doing enough to address the youth vaping “epidemic.” Meanwhile, the FDA continued to punt on decisions for the biggest players.

Bundling and Bracketing

The August 19 memo shows, however, that CTP’s OS envisioned a different reality in the beginning and laid out this “bundling-bracket approach” to “(1) increase the likelihood that a variety of products for which marketing is determined to be APPH will be legally marketed by the end of the compliance period; increasing the availability of tobacco products that help adult current [tobacco product] users switch to potentially less harmful products; and “(2) increase the likelihood that a greater number of [products] for which marketing was determined to not be APPH be removed from the market.”

CTP expected this process to allow its scientific reviewers to apply conclusions to categories of products rather than evaluating each one separately.

The first step, “bundling,” refers to the process in which CTP would organize applicants’ PMTAs into smaller subsets prior to scientific review. The next step, “bracketing,” refers to “the process of individually evaluating the highest and lowest variation of a given characteristic within the bundle (i.e., the highest and lowest nicotine concentration for purposes of this memo) and bridging the findings and conclusions to all other products within the bracket (e.g., products with nicotine concentrations between the highest and lowest nicotine concentration).”

CTP would use this method, the memo describes, for “ENDS open e-liquid PMTAs” that contained more than 24 tobacco products, two levels of nicotine concentrations, and more than one PG:VG ratio—criteria that certainly applied to a plenty of them.

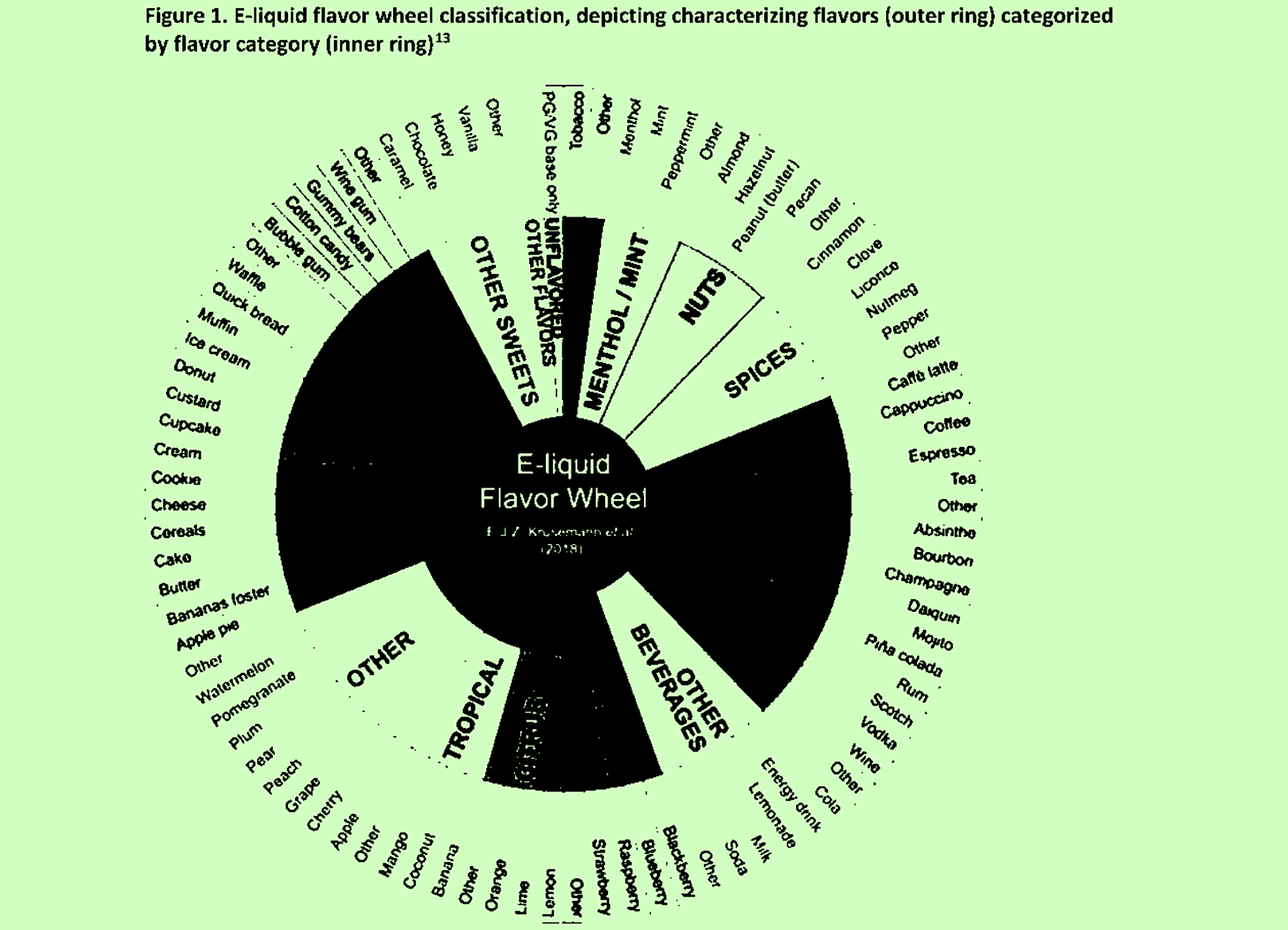

CTP basically expected this process to allow its scientific reviewers to apply conclusions to categories of products rather than evaluating each one separately. Classifying groups of flavors together according to a “flavor wheel” (pictured top) was one way of doing this.

There are several different divisions within CTP which, naturally, evaluate different parts of a PMTA: Among them, the Division of Product Science comprises chemists, engineers and microbiologists who determine what’s in a given product, and the Division of Nonclinical Science is made up of toxicologists who determine health impacts.

According to the memo, then, “Division of Product Science (DPS) and Division of Nonclinical Science (DNCS) reviewers are able to conduct individual scientific review on a maximum of 24 CFs within any single PMTA due to resource limitations. However, there is no limit to the maximum number of tobacco products per PMTA for which the conclusions can be bridged.”

“The short version is there seems to be one set of rules for the applicant to establish APPH (every product has to have complete information) and one set of rules for CTP reviewers (you don’t have to read and review everything),” a former CTP employee, who requested anonymity so as not to effect their career in tobacco control, told Filter.

“FDA has allowed itself the kind of efficiencies it should have offered applicants—batching and bracketing thousands of near-identical products.”

More specifically, the memo details each step CTP’s Office of Science would take:

1. “After a PMTA is accepted and filed, it is placed in the queue for triage randomization before the start of scientific review. If selected for scientific review, the application is reviewed to identify CFs and variations of nicotine concentration and PG:VG ratio”

2. “Assign submitted CFs to flavor categories based on flavor wheel”

3. “Calculate the percentage of tobacco products in each of the flavor categories within the application”

4. “Randomly select 24 CFs, proportional to the percentage of flavor categories in the PMTAs based on step 3”

5. “Bracket products by reviewing two products for each of the 24 selected CFs: the highest and lowest nicotine concentrations, both with the highest VG within the PG:VG ratios.”

“It’s clear that FDA allows itself efficient shortcuts that it has denied to applicants,” tobacco harm reduction advocate Clive Bates, the former director of Action on Smoking and Health (UK), told Filter. “The problem has always been that FDA’s extraordinarily burdensome process was obviously tremendously wasteful for applicants, but of course it was alway going to be unmanageable for the assessors in FDA. Without this sort of shortcut, the PMTA process would have become a human resources nightmare. So FDA has allowed itself the kind of efficiencies it should have offered to the applicants—batching and bracketing thousands of near-identical products.”

“It seems waste and red tape is OK for the regulated,” he continued, “but something to be sidestepped by the regulator.”

The August 19, 2020 CTP memo:

Image of flavor wheel adapted from the CTP’s memo

Show Comments