By every measure, the global drug war has failed. It has failed to decrease drug use and sales. Drug-involved overdose deaths continue to soar around the world. And violence related to the illicit markets created by prohibition wreaks havoc on individuals and communities.

The drug war also continues to enable racist policies and practices. Black, Brown and Indigenous people are disproportionately targeted by punitive drug law enforcement and overrepresented in prison populations worldwide.

Every year over $100 billion is spent on global drug law enforcement. This is more than 500 times the amount invested in harm reduction services for people who use drugs. Prioritizing punitive enforcement over interventions which protect the health of people who use drugs is a political choice made by many governments. This approach violates human rights, drives stigma and discrimination, and has no impact on drug use. As well as being expensive for governments to implement, it places additional economic burdens on public health, communities and the individual, further amplifying inequalities.

Combining crime and drugs frames the issue in a way that impedes any real progress.

Decades of advocacy by drug policy reformers and human rights activists have resulted in a recognition of the magnitude of the damage done by the drug war’s punitive logic. As we reimagine drug policy, it is essential that we question who is best placed to respond to drug use and sales—and that we advocate for the redirection of funds within local, national and international budgets, away from punitive drug control towards compassionate and effective health and community programs.

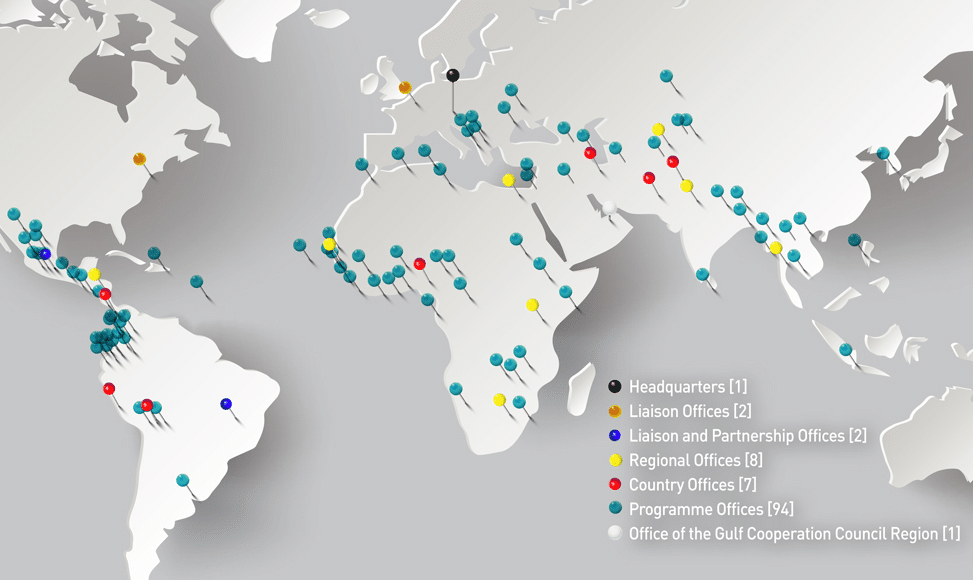

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) is the primary agency upholding the drug war at the international level. But is the UN agency tasked with dealing with crime also best equipped to lead on health-based responses to drug use? Combining crime and drugs frames the issue in a way that impedes any real progress. As a result, we see a focus on punishment and repression.

This is reflected in the lack of explicit reference to harm reduction in UNODC’s strategy and illustrated, for example, by UNODC’s support for drug detention facilities in Sri Lanka and elsewhere, where human rights abuses have been reported.

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in the United States exemplifies the perverse priorities and outcomes of the misguided “War on Drugs.” In 2019, it had a budget of over $3 billion. Despite continued heavy expenditure, it has failed in its goal of decreasing drug supply into the US, has fueled mass incarceration and racial disparities, has a history of further human rights abuses, and is riddled with scandals at home and abroad. The damage is exported, as millions of dollars from the DEA’s budget are used for international activities.

Specialized drug enforcement agencies make up a sizable part of the global drug-war budget, but they are by no means the whole pie. The wasteful, harmful expenditure is furthered by police and prisons, both of which dehumanize people and violate human rights.

In 2019, the total budget for harm reduction in Thailand was estimated to be $1.7 million. In contrast, the Thai government allocated around 1,500 times this amount—more than $2.5 billion—to drug law enforcement activities.

The Indonesian government, meanwhile, spends up to $250 million annually on punitive drug control and allocates only $400,000 to harm reduction initiatives. Prisons there are filled to double their capacity, with an estimated 39 percent serving drug-related sentences and 15 percent imprisoned for drug possession for personal use.

In order to effectively advocate for a redirection of funds, we need to map what is being spent.

Criminalization also imposes debilitating financial costs on individuals and their families. Average legal fees, court processing charges and bail charges far exceed the average monthly income in Indonesia, thereby compounding the poverty and inequality experienced by many impacted people.

In order to effectively advocate for a redirection of funds, we need to map what is being spent. Harm Reduction International’s costing tools are designed for advocates at the local and national levels. They can be used to calculate expenditure on punitive drug law enforcement versus that on health and harm reduction programs rooted in compassion and evidence of efficacy.

The first step to divesting from failed, punitive drug policies is questioning which bodies are best suited to respond to drug-related issues. The second is to advocate for drug-war funding to be redirected—and invested in social and community programs for all people.

Map of UNODC offices around the world via UNODC

Show Comments