In early July, for the first time since COVID-19 protocols were lifted in April, a general-population prisoner at Washington Corrections Center (WCC) tested positive for the virus. Staff took him out of the living unit and into quarantine, then asked the people he’d been in close contact with to get tested. They refused.

Rapid antibody testing, which might otherwise be considered one of the more innocuous COVID precautions, gets the most visceral reaction because in here, it creates more harm than it reduces.

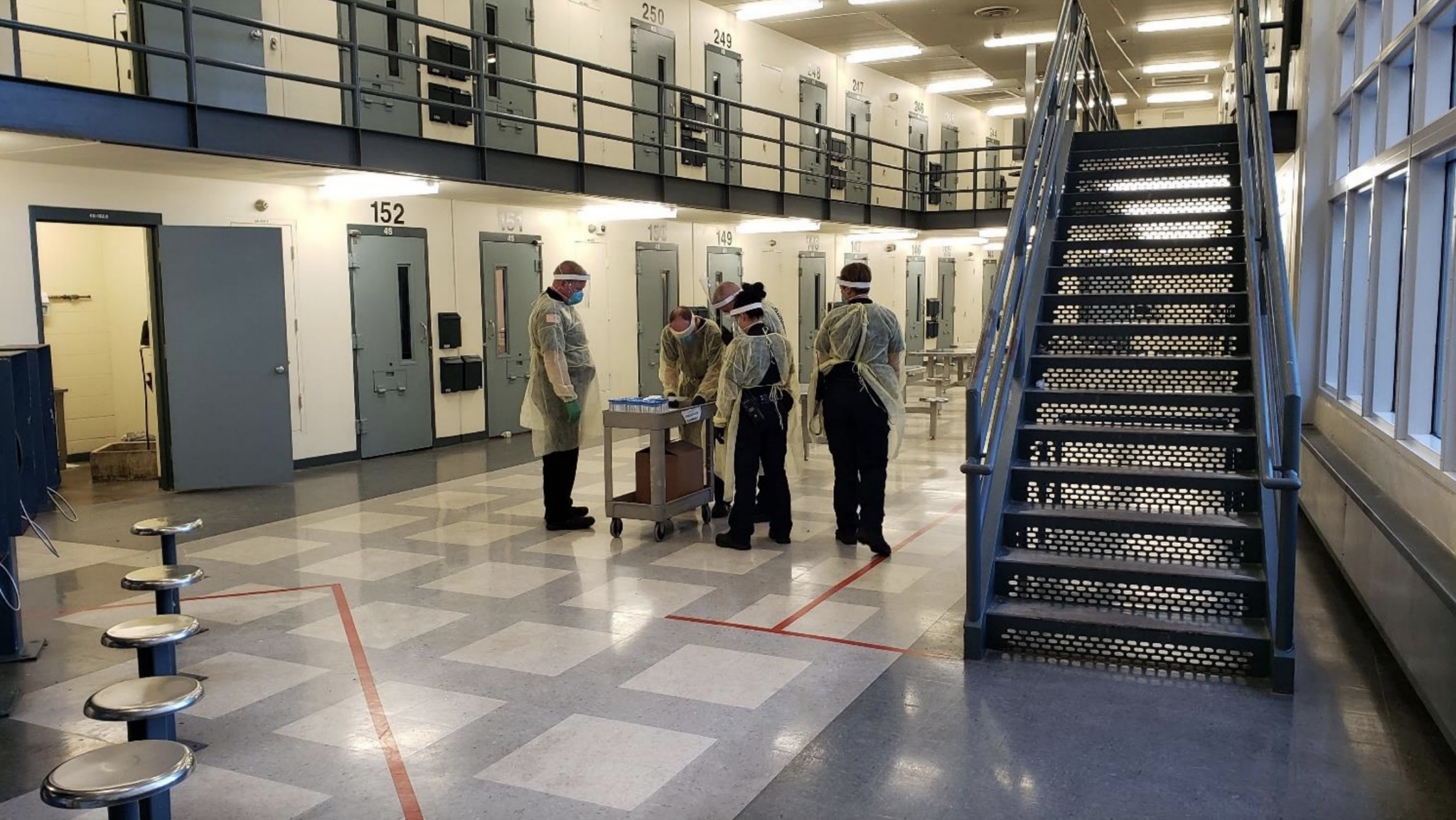

In prison, lockdowns are literal. During the pandemic we were locked inside our tiers 23 hours a day, with a one-hour allowance for outside recreation. No visitors. No volunteers. No educational or recreational programming. No ice, which is a critical resource during the summers; ice machines are located outside the tier. Food was brought to us, cold and soggy in Styrofoam clamshells. No contact with staff, except for when they put on PPE to bring the soggy food or sometimes pass out mail.

Constant testing did nothing to reduce COVID transmission, but it was very effective at reducing everything else. From a few weeks into the pandemic through the end of 2022, each time one of us tested positive, staff would pack us off to the quarantine unit. We’d be locked in there with a bunch of other people who’d also tested positive, until we tested negative. No TV. No radio. No books. We had the option of making one 20-minute phone call each day, during the same 20-minute window when we had the option of taking a shower.

We lived like this for more than two years.

In the meantime, staff would place our tier on isolation and test everyone a few at a time, and accordingly disappear them into quarantine a few at a time. The whole tier—30 cells, each housing two people—would of course ultimately test positive, but this would take about two weeks, during which time the people in quarantine would start testing negative and being brought back to the tier.

We lived like this for more than two years. Either we were in isolation or we were in quarantine, except when being shuffled from one to the other. Then, in late 2022, prisoners in Airway Heights Corrections Center changed the game. Instead of complying with orders to get tested, many of them signed the form that releases Washington State Department of Corrections from liability when someone in its custody refuses a treatment or procedure against medical advice. Word spread to other facilities.

Now that COVID is not longer classified as a public health emergency, we’ve been assured that, no matter what happens next, it won’t be a return to lockdown protocols. But most of us in WCC were more harmed by the way COVID precautions were enforced than we were by COVID, and because of that we haven’t spent too much time evaluating the merits of each precaution individually. People do not intend to get tested, and they also do not intend to get vaccinated.

The main thing actively driving vaccine hesitancy in here is toxic masculinity.

Vaccine hesitancy in prison is rooted in the same distrust of government and medical institutions as it is on the outside. But the main thing actively driving it is essentially toxic masculinity. In prison culture especially, that tends to mutually reinforce an overdeveloped sense of confidence, to cover an overdeveloped fear of being perceived as weak.

Everyone here got COVID, but not everyone got sick. Getting sick, and by extension getting a vaccine that meant acknowledging the possibility you could get sick, is a sign of weakness. That’s not something you want to show in prison.

I’ve had COVID four times, but I only got sick twice, and of those two times one still wasn’t that bad. The other was bad. Aside from the fever and sweats and chills, what I remember most is a feeling like my lungs were filled with molasses.

Unlike most people on my tier, I was vaccinated at the time. After that, I stopped getting the shots. Why bother?

The irony lost on me until recently is that I’ve been living with HIV for more than 30 years, and I’ve talked to so many people about the importance of mitigating viral transmission that people knew me as “the AIDS Guy,” and they meant that with a certain level of respect. But I’m not much more immune to toxic masculinity than I am to COVID, and I just hadn’t been thinking about the vaccine that way.

Now that COVID has returned to the living units, I requested an appointment to get vaccinated again. Since making that decision, I’ve also started talking to the guys on my tier about why testing and vaccination in this context are separate things. One is used here to increase harm, the other to reduce it.

Photograph via Minnesota Department of Corrections

Show Comments