Created in the spring of 2020, the New York City Methadone Delivery System (MDS) was the first program of its kind in the country, a collaboration between the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) and the New York State Offices of Addiction Services and Supports (OASAS).

“The MDS was developed to fill an emergency need during the pandemic for people who were unable to get to their [clinic] due to having contracted COVID-19,” Evan Frost, the Assistant Director of Communications & Public Information for OASAS, told Filter. “[People] who are quarantined for direct exposure to the virus, or vulnerable to risk of infection, and also are unable to identify an alternative person approved to pick up and deliver medication.”

The program started making deliveries in April 2020. One year in, it “turns out we serviced a lot of people who were on daily doses,” said DOHMH Senior Director of Research and Surveillance Denise Paone. “That becomes very draining on the system. It’s not sustainable … we made the case that it’s a good policy to give 14 or 28 days, but we never said we won’t deliver if [they don’t].”

There are an estimated 28,500 registered methadone patients in New York City, more than half of whom are over the age of 45. The program has made about 4300 deliveries, to about 958 individuals, as of March 7 (the most recent data available as of publication time). “We thought there would be more people given the relaxation of the federal regs,” Paone said.

The medication is delivered by a courier in large metal lockboxes provided by DOHMH. Brooklyn has received 34 percent of the city’s deliveries; The Bronx, 20 percent; Queens, 24 percent; Manhattan, 18 percent (Staten Island isn’t part of the MDS).

“A lot of the deliveries kept people safe from overdose by maintaining their access to medication, kept people safe from COVID and allowed sick people to stay home,” said Allegra Schorr, president of the Coalition of Medication Assisted Treatment Providers and Advocates (COMPA) and the owner of a methadone clinic in Manhattan.

Schorr acknowledged that there was never any plan or possibility of delivering to all 28,000 patients. “Hopefully, as more patients receive vaccines, the need for MDS will diminish.”

But why haven’t more patients been referred to the MDS? There are two reasons: money and power.

Medicaid reimbursement for methadone clinics varies by state. In New York, it’s a fee for each service performed—like when a patient comes to the clinic and takes their medication under supervision. There was no reimbursement for doses taken at home because they are unsupervised.

Clinic staff also wield enormous power over patients by controlling access to the medication that they need to go about their daily lives. Patients are threatened with loss of access to their medication if they violate clinic rules. Staff can arbitrarily deny take-home doses needed for a patient to travel (or to stay home). This dehumanizing power dynamic is baked into the structure of every opioid treatment provider (OTP).

Rethinking a Punitive System

COVID forced a reckoning with how methadone clinics operate. It exposed all the ways that clinics are obsolete, and how overdue the US is for a new paradigm for providing methadone—one grounded in dignity, respect and autonomy.

In March 2020, as COVID began to spread across the country, state officials directed the public to shelter in place. That was already a nonstarter for people in methadone programs. The daily travel requirement of the clinic system is a hardship that is rarely acknowledged outside of harm reduction circles. Many participants have to get to their clinic—sometimes an hour or two away—five or six mornings a week. If you’re late, you can’t get your medication. If you can’t get your medication, you can’t function.

“My clinic has been an absolute mess since COVID.”

The pandemic severely disrupted the lives of methadone patients because of inflexible clinic regulations. There are the mandatory counseling groups; the urine collection; the in-person bottle counts. Clinics are often crowded, and patients wait outside in long lines for the clinic to open, and then long lines inside to get medicated.

“My clinic has been an absolute mess since COVID happened,” Samantha, a methadone patient in Connecticut who is currently pregnant, told Filter. “It was ridiculous to line us up outside in the freezing cold weather while they let in two people at a time. It was pointless.”

A social worker and small-business owner, Samantha has to be at her clinic by 4 am each morning to get to work on time. “By 5:30 am the line is already down the street and it takes hours to get your medication,” she said. “The clinic could have handled COVID better. Have longer hours—better yet, open at night, make appointments, hire more nurses and of course give [more] bottles.”

People with substance use disorders—particularly those with opioid use disorder (OUD)—are more susceptible to COVID. In the early days of the pandemic, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) rolled out temporary guidelines revising the take-home dose policy.

Patients who were deemed “stable”—a subjective determination left to each OTP, which left behind many unhoused and mentally ill patients—could receive either a 14- or 28-day take-home supply. The bar is set high to qualify for additional take-home doses: no recent drug use, regular clinic attendance and a stable home environment and social relationships.

Racial disparities are stark. Black and Brown communities are disproportionately impacted by COVID; Black people with OUD are four times more likely to develop COVID than white people. In New York City, over 70 percent of methadone patients are Black or Brown.

In North Carolina, a study conducted in three clinics with the involvement of the North Carolina Survivors Union (NCSU) showed how much take-home dosing experiences varied by clinic. It also found that less than 7 percent of participants reported selling or giving away their take-home doses—belying the obsession that the DEA has with diversion.

Clinics “should reduce barriers to treatment during COVID-19 and consider expanding access to take-home doses while providing harm reduction messaging to their patients,” the authors concluded. “[W]e should make treatment more accessible, not more restrictive.”

Looking Beyond the Pandemic

The NCSU, alongside more than a dozen other organizations, made a series of radical recommendations to increase access and to save lives: expand office-based treatment; deploy methadone vans; expand methadone telemedicine services; suspend all toxicology testing; end administrative detox “feetoxs”(a term for what happens when patients don’t pay clinic fees) and suspend the X waiver for prescribing buprenorphine.

At Montefiore methadone clinics in The Bronx, which predominantly serve the Latinx and Black communities, providers worked quickly in the early days of the pandemic to decrease in-person dosing. Between March 9 and 22, 2020, the proportion of patients with five to six clinic visits per week dropped from 47.2 percent to 9.4 percent. No overdose deaths were reported.

All urine testing on established patients was halted. Prior to the pandemic, Montefiore staff directly supervised the collection of toxicology samples, meaning they watch participants urinate. The process is humiliating, and a positive screen can result in the loss of take-home privileges. Toxicology testing “should not receive disproportionate weight as a criterion for unsupervised dosing,” the researchers wrote in a paper on their work.

“We have resumed testing on a limited basis when it helps to inform clinical decision making,” said Dr. Shadi Nahvi, a co-author of the Montefiore paper. “I hope that the lessons we learned during pandemic care delivery will shift nationally, away from testing by routine to using testing when it is clinically informed and patient-centered.”

Urine testing is not voluntary, and positive results can and do result in punishment. As long as these two things are true, urine screening cannot be truly “patient-centered.”

Why did it take a pandemic to enact these changes, and to recommend that methadone clinics center the needs of their patients?

It’s enraging that it took a pandemic for OTPs to loosen restrictions on take-home doses. Advocates want this policy to be made permanent when the coronavirus is eradicated, as do many involved with the MDS program.

“New Yorkers who take methadone and get sick from COVID-19 should not have to choose between getting their medication and protecting their health or the health of others,” said former NYC Health Commissioner Dr. Oxiris Barbot in a May 2020 press release. “No other medication is as strictly regulated as methadone, and I urge my federal colleagues to consider making these changes permanent after the pandemic is over.”

“We need a fundamental shift in the framework of how methadone is made accessible to people in this country.”

But it appears the more flexible take-home bottle policy might not be permanent. “I usually get 13 take-homes, the max in our clinic,” Samantha said. “In the beginning of the pandemic I was allotted 27 bottles. In November of last year, they lowered it back to 13 and didn’t tell me why.”

“COVID-19 made one thing abundantly clear,” said Biz Berthy, drug policy organizer at VOCAL-NY. “We need a fundamental shift in the framework of how methadone is made accessible to people in this country.” One way to do that is by defunding methadone clinics and, instead, funding a pharmacy-based pick-up system—like those that already exist in Australia, Britain and Canada.

Activists across the country are organizing to empower people who use methadone to fight for their rights. The Urban Survivors Union (USU) has just released a call to action, The Methadone Manifesto.

“The relaxed COVID-19 SAMHSA guidelines allowing for expanded take home dosing eligibility established in the spring of 2020 are the most policy change the methadone clinic system has seen in decades,” the Manifesto concludes. “A huge opportunity for patient organizing for greater reform has arrived, and we as a community of patients and people who use drugs must seize it.”

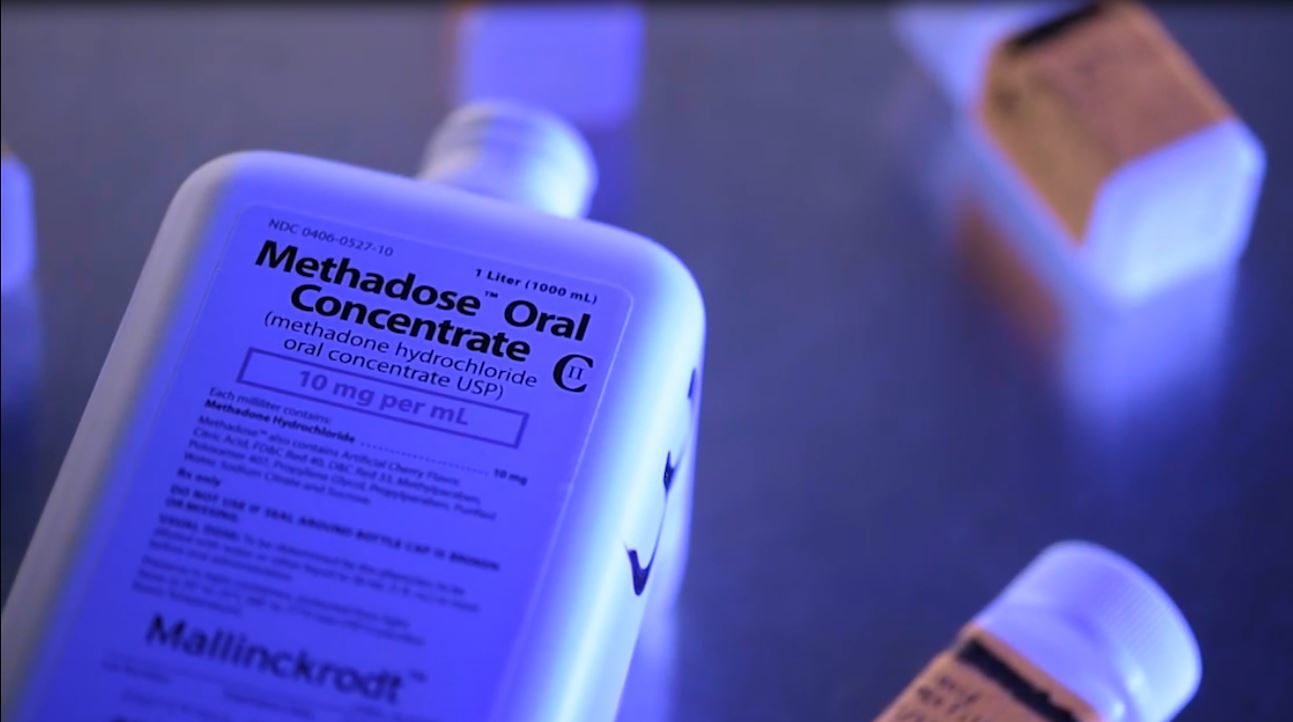

Top photograph via New York State Office of Addiction Services and Supports. Middle photograph courtesy of New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Bottom photo by Helen Redmond.

Show Comments