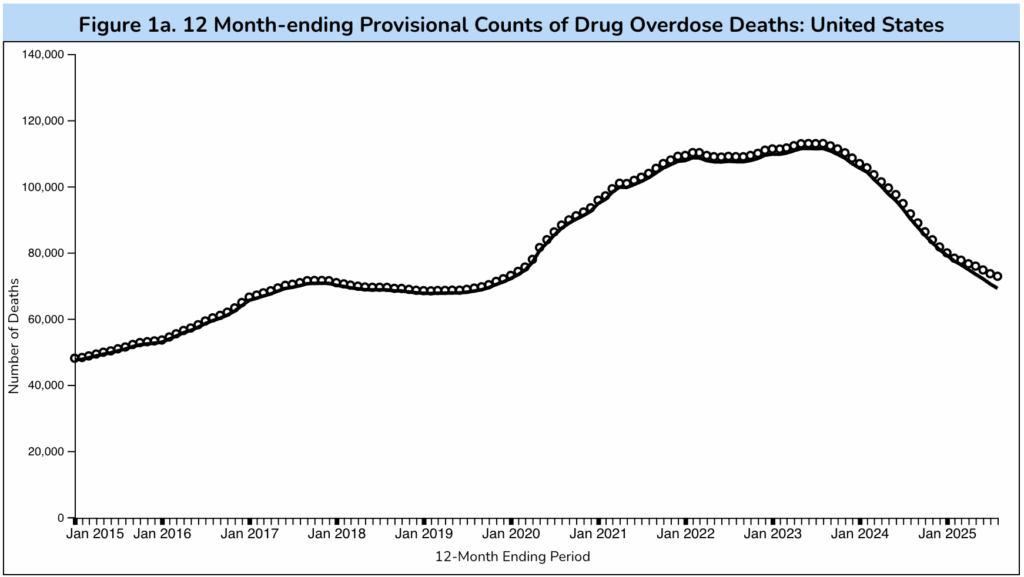

On January 14 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published its monthly provisional overdose death count—the first such update since September 2025, before routine government operations were disrupted by the federal shutdown. The newly released data cover the 12-month period leading up to August 2025 and show that the death rate is still dropping, but not as sharply as it has been.

The United States has so far recorded 69,172 overdose deaths between August 2024 and August 2025, a preliminary figure the CDC predicts will ultimately level off at 72,836 deaths as the last of the data trickles in. The highest 12-month provisional death count was exactly two years earlier, with 111,451 predicted and 112,996 reported deaths in the year before August 2023.

The death count has now been falling for more than two years, which is unprecedented in the nearly three decades the CDC has been tracking overdose mortality. The rate climbed steadily each year until around 2014, when it began to climb more rapidly as fentanyl supplanted heroin in the street opioid supply. Except for a slight decrease in 2018, overdose deaths had gone up each year until 2023. This latest update puts the death rate about where it was in 2017.

The new data show that the US death count is a staggering 23 percent lower than it was a year earlier. But it’s not as steep a slope as what we saw when the overdose trajectory first turned around.

In May 2025, for example, the CDC announced that its provisional death count for 2024 was 80,391, a decrease of almost 27 percent compared to the 110,037 deaths from its provisional data for 2023.

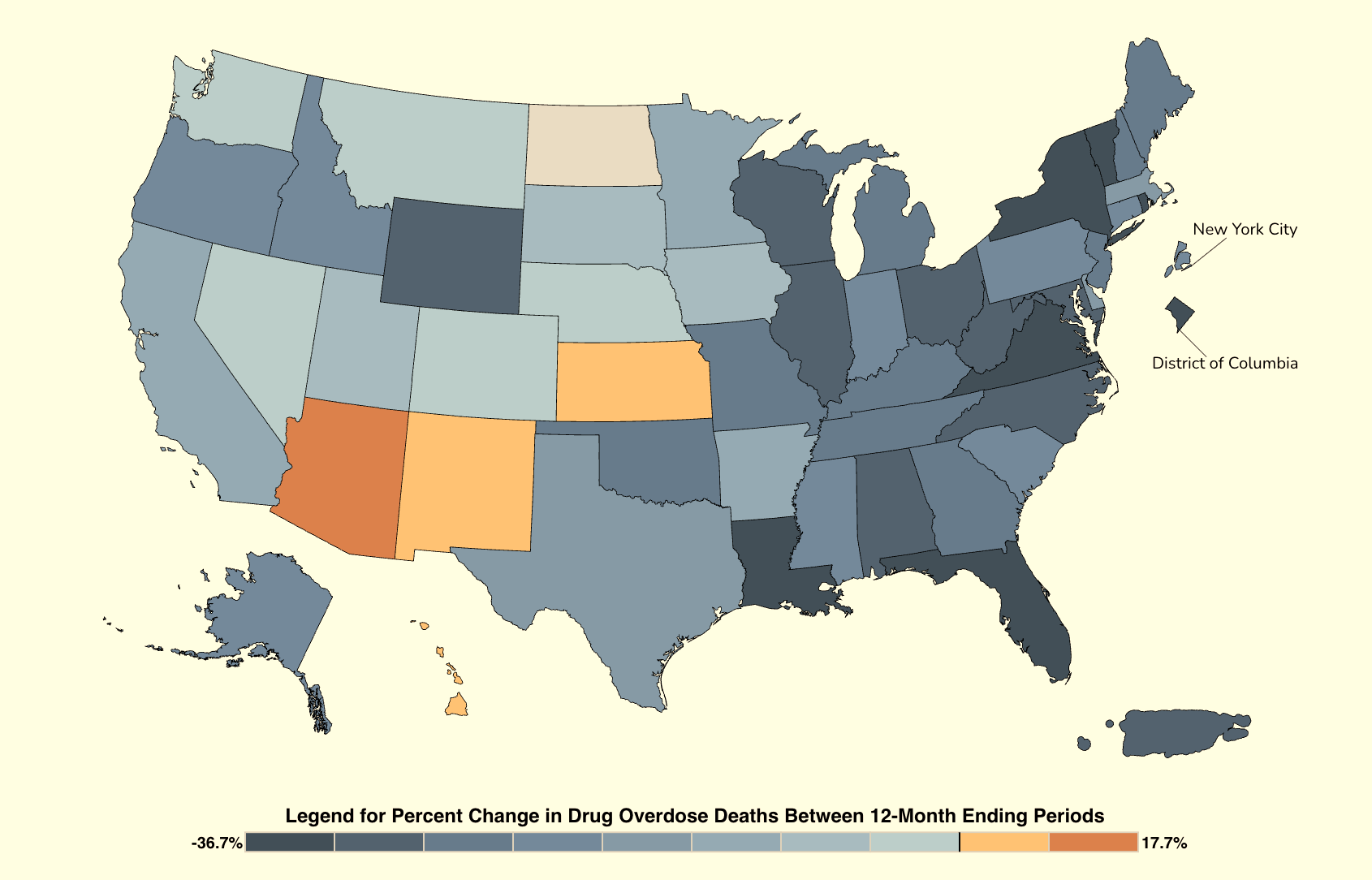

All these figures are national averages, and overdose has never been geographically uniform. In at least three states overdose deaths appear to be going back up.

Kansas, New Mexico and Arizona have already reported more deaths from between August 2024 and August 2025 compared to the same period a year earlier, and the CDC projects that Hawaii will follow once the rest of the data are added. North Dakota’s rate stated exactly the same, and though in all other states overdose appears to have decreased, a number of them may look very different in the final data than they do in the provisional data.

Massachusetts, for example, reported 1,904 deaths for the 12-month period prior to August 2024, and so far has reported 1,096 for the period before August 2025—a drop of nearly 42.5 percent. But the CDC predicts that the state will ultimately report another 467 deaths for the more recent period, bringing the rate of change down to just under 18 percent.

A handful of theories have been floated as to why the trajectory of overdose deaths suddenly turned around two years ago. The most recent one to get traction argues that the change was likely set in motion by China, as the result of a crackdown on the fentanyl supply chain. Supply interdiction is always popular with any administration, but no matter how loudly the Drug Enforcement Administration or Customs and Border Protection yell about how many pounds of fentanyl they’ve gotten off the streets and how many millions of hypothetical lives they just saved, the drug supply is not finite.

On the rare occasions that supply-chain disruption has produced evidence of fewer deaths or a smaller drug supply, these are invariably short-term results before the situation evolves into something different and worse. The CDC data might align with that.

By the time the CDC gets these numbers they’ve already been subject to a huge amount of distortion at the local level, and are then distorted further by the media. Some things are overcounted, some undercounted. But they do help us understand the overdose crisis in terms of overall trajectory and sense of scale, especially in the context of how much enforcement and criminalization the country has piled on over the years. In 1999, the earliest year for which CDC data are available, the reported death count was 16,849.

Images (cropped) via Centers for Disease Control and Prevention