“Wake up!” my wife screamed for the thousandth time, her normally calm speaking voice edging into anger. The rubber band in her hair signified her readiness for combat.

It was almost 8 am. My dosing window at our Indianapolis methadone clinic started at 9 am, and the clinic was notorious for arbitrarily closing its doors mid-morning. We lived an hour and a half away—but only if there was no traffic. In order for our mighty red Civic to get us there without risk of missing our dosing times, we had to leave now.

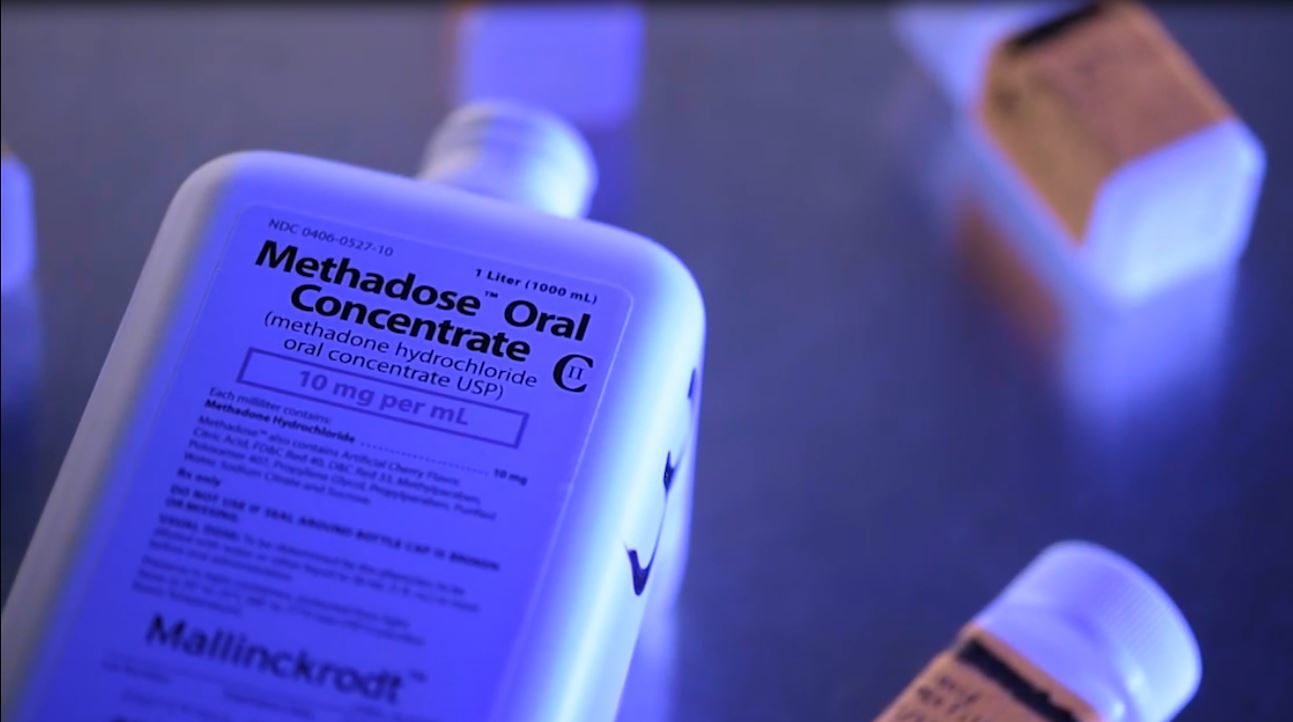

I got up, washed my hands and face, and got dressed. I almost made it out the front door, then remembered I hadn’t grabbed the bank-level security lock bag containing my 27 empty take-home bottles—that all-important blue nylon bag that held my bottles of joy. I’d forgotten that bag and had to drive all the way back to get it enough times that that lesson was finally sinking in. My wife got the keys, we got our coffee, and hopped in the car for our monthly trip to the clinic.

This was in 2016. I’d just turned 40. I’d been at this clinic off-and-on since I was 18. I’d been through at least 15 counselors, four directors and about 100 nurses. More people had handled my urine than I could count. Ah, urine, that vital fluid, the be-all and end-all of a methadone patient’s fate. I’d gotten a couple false positives in the past—and racked up large bills proving they were false.

I was now going on 10 consecutive years in the clinic, and I was full of confidence. I knew I wasn’t using. I knew I had all my bottles with all the right dates on. I knew that I was okay.

When we got there, I joined the 10-person line forming outside—small, considering the line sometimes stretched in a meandering crisscross all around the large parking lot. I checked my cracked-screen phone and breathed a sigh of relief: 9:25 am.

But when I reached the nurse’s station, I realized this was not a nurse I knew. Her panda-motif scrub top was crisp and new. This is always a moment of dread for any clinic patient. Will she be kind? Will she be mean? Will she want my pee?

All joy fled at her weirdly gleeful exclamation.

I put on my patented, go-to clinic persona: Courteous and Polite. I handed her my bottles and watched as she counted them. She set them in front of her; everything seemed to be going fine. But then her beady eyes turned to something only visible to someone looking to find it.

“This lid is not right!” she exclaimed. All joy fled at her weirdly gleeful exclamation.

I told her that the lid had to be right, because a clinic nurse had given it to me.

“We’ll see about that,” she replied.

I was petrified. How could my years of work be jeopardized by a person so eager to dole out punishment? Her squared shoulders and the hands balled on her hips told me right away that this was gonna be a long fight.

After a lot of back and forth, the nurse still insisted that the bottle lid was wrong. I was sent to my counselor to talk about my apparent bottle lid problem. I explained to my counselor, an ex-pastor, that I had seen the lid, and that it was an older type that the clinic had been using a couple of months ago.

He put out his smooth hands to me and started a prayer. His generic ministrations felt like a death knell.

“Damnit,” I thought, “I’m fucked.”

The battle raged for weeks. During much of that time, I was demoted to daily dosing. I took pictures of that exact type of lid in a box labeled “lids” in the clinic office. I provided endless proof of my “good” record. Nothing seemed to matter.

Eventually, we had a big meeting with the clinic director and the State Opioid Treatment Authority (SOTA). The SOTA was a tower of a man with a bevy of gold rings that would shame a pimp. He had an easy manner born from struggle. We shared a lot of the same life experiences that drug use brings. The SOTA was on my side. He said that the state was okay with giving me back my take-homes. I was being backed by authority—a new experience for me.

Yet the clinic director, acting on all the wisdom she’d accumulated in her 28 years on this Earth and her three years in the methadone biz, said she could not prove that it wasn’t “diversion.” The SOTA was blown away; it showed in how he wrung his giant hands.

The SOTA is responsible for maintaining the clinic according to state laws. I’d thought that having him on my side would be enough. But it turns out that if a clinic director says that they can’t guarantee diversion did not occur, the state can’t intervene. No laws were broken; there was nothing the SOTA could do for me but advise.

To go from having to make a three-hour round-trip drive once a month to doing it every single morning is debilitating.

The SOTA actually sat there the whole meeting and stuck up for me, exclaiming that the state would go to bat for me at the federal level if needed. But in the end, the clinic won.

The triumphant clinic director offered me a week of take-homes instead of a month’s worth. She told me this was a courtesy. I told her there was a special place for people like her.

The SOTA still tried in vain to comfort me and offered a lot of good-hearted suggestions. But I was absolutely done.

I’d resisted the temptation to request my dose be raised as high as it could go. I was actually slowly tapering my dose. I had even bought into the idea that higher doses meant I was trying to “get high.” God, I could have used an introduction to harm reduction right then.

I had been in a great place in my life. I had just bought a house, got my kid through 20 surgeries, and married the most amazing human I had ever met. I was trying to get off social security and look for work. This clinic fiasco was one of the worst things that had ever happened to me.

To go from having to make a three-hour round-trip drive once a month to doing it every single morning is debilitating. But just as crushing is the knowledge that you have no power in your own treatment, and that nobody believes you.

It’s hard to explain this to someone who has not been through it. You struggle to get to a stable place at a clinic that doesn’t even care about you. You follow their rules, even when they seem counterintuitive. Then, over something as arbitrary as a “wrong” lid that came from the same place that gave you your bottles, your daily life is upended and hobbled.

In the end, I went back to cadging quack doctors for methadone prescriptions for pain. I would rather trust the lies I’m telling them than the lies the clinic tells me.

A slightly different version of this story was originally published in The Methadone Manifesto by Urban Survivors Union.

Photograph via New York State Offices of Addiction Services and Supports

Show Comments