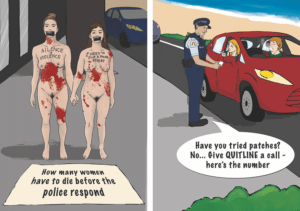

On a main city street in Auckland, New Zealand last month, two women staged a protest against police inaction over violent assaults against women. Naked, with black gaffer tape across their mouths symbolizing that they felt silenced, fake blood smeared across their bodies and pooled at their feet, they stood for one brave hour. Across their chests was scrawled “Silence is Violence” and “I need to file a police report.” On cardboard at their feet was written, “Do women have to be dead before police respond to violence?”

The next day, New Zealand’s Associate Minister of Health Jenny Salesa announced that she would be banning smoking and vaping in cars when anyone under the age of 18 is present. Once the law is changed, police will be required to look for puffs of smoke swirling inside vehicle cabs and sneaking out the window. Because it’s difficult to discern if an adult-sized body is under 18 from a distance, the police will have to get alongside vehicles to peer inside or simply pull all drivers over if anything resembling smoke or vapor is seen.

Concept: M Glover; Artwork: Burnt Orange Ltd

Having found an offender, depending on their biases and mood at the time, the officer can choose whether they just give a warning, give stop-smoking advice and a referral to a cessation support service, or issue a NZ$50 fine.

Over half of women in prison in New Zealand are Māori. Smoking rates among Māori mothers of children under 18 are the highest in the country.

The latter is the most likely outcome for Māori women, given the well documented problem of racial profiling by police. Over half of women in prison in New Zealand are Māori. Quite apart from that, Māori women will be disproportionately harmed by this law change purely because they are over-represented among the most vulnerable and poorest groups in society, who smoke the most. Smoking rates among Māori mothers of children under 18 are the highest in the country, and depending on the socio-economic area, will range upwards from the Māori female average of 38-50 percent or more. For context, only 12 percent of European (mainly white) New Zealand women now smoke.

The proposed law will also require police to check parked cars. In New Zealand—where smoking is banned in nearly all indoor places, many outside town centres, parks, beaches, hospital grounds and university campuses—cars have taken on new significance for people who smoke. Vaping, a crucial form of non-coercive harm reduction, has also been banned, or is set to be, in all these places. With the law change, smokers might close their car windows when smoking, potentially increasing the potency of the sidestream smoke for the occupants.

New Zealand society, the government claims, wholeheartedly supports the proposed law change. A range of surveys report from 63-96 percent support. But the survey questions were all highly leading, providing no hint of the negative consequences that could result if the law was passed—including jail time for failure to pay fines—or the certainty that these consequences will be racially disproportionate. Participants were led to think only of very young children, and were not told they’d also be supporting banning vaping in cars. Any fair-minded but uninformed person would be likely to tick “yes” to questions framed this way.

Neither were respondents asked to ponder the opportunity cost of making the police enforce such a law—the cumulative effect of the time and money that will have to be redirected away from other things the police could be doing. Like investigating violent assaults against women.

Adopting positively focused measures like encouraging risk-reduced alternatives to smoking would be far more effective at reducing harms.

New Zealand has a great reputation for being a very safe country to visit and live in. We do however, suffer shockingly high rates of child abuse and suicide. Violence against women is a persistent scourge.

When victims of crime have to take to Twitter to get police to investigate an aggravated home invasion, or protest naked on the streets—not just for themselves, but for all victims of violence who are being waved away like annoying flies—we have a major problem with our priorities.

Appropriating police time to selectively harass, criminalize and punish vapers and smokers and foist cessation advice upon them—as if it would be likely to work in that context—for something that is a dwindling cause of harm is seriously warped. Doing so at the expense of police work that should be prioritized is a failure of justice.

Adopting positively focused measures like encouraging risk-reduced alternatives to smoking would—as we have seen in countries like the UK—be far more effective at reducing harms without increasing the racially biased trauma of heightened police intervention.

Top photo by Michael Skok on Unsplash

Show Comments