It’s afternoon on the Monday after the Fourth of July. My daughters, ages five and six, sit perched on the edges of their beds. They are surrounded by a wealth of toys. Stuffed animals, dolls and furniture are strewn across the scene—I’ve lost count of the Elsas—and the shelves are bursting with doll clothes and accessories, animal figurines, board games, puppets, stray crayons and stickers, hair clips and jewelry gaudy with glitter. And yet, they are ignoring this childhood treasury, both sitting with shoulders slumped, their bodies tensed and uncertain, their eyes round and distant.

“I wish I could live with you, Mommy,” says my littlest.

“Me too,” says her sister. “Is that natural?”

I say nothing, wanting to gather her in my arms, and Littlest answers instead. “Yes. That’s normal, living with Mommy and visiting Grandma. That’s normal.”

“I want to be with you always, I love you both so much,” I tell them. I don’t know how to make them know, to really know and feel, that I am leaving because I have to, not because I want to.

My elder daughter pulls her little blankie—the one she’s had since she was a baby—close to her chest and pops her thumb in her mouth.

This is their home, their life, as assigned by Broward County and Florida Department of Children and Families (DCF). It’s the home of their paternal grandparents, who initiated the child welfare case against me. Their grandfather, who has since become completely paralyzed and unable to speak, requires their grandmother’s constant care.

I have written about my case for Filter and other publications in the past. About how my daughters’ paternal grandparents called a child abuse hotline to accuse me of drug use and abandonment while I was staying with them in Florida, and testified against me in family court in 2018. About the barriers the authorities placed in my way—like failing to facilitate or allow my access to evidence-based opioid use disorder treatment—before proceeding, on the basis of misconceptions about drug use and addiction, to deem me an incurable failure and place my case on an adoption track.

Now, I’m writing about the predictable outcome of that: how they permanently terminated my rights to my two little girls, who still beg to come home to me.

Sometimes, the agency arranges a final meeting, where the parent must explain to their child that this is the last time they will see each other.

Termination of parental rights is termed the “civil death penalty.” It permanently severs the legal bond between parent and child. The parents’ names are removed from the birth certificate, erasing any record of the relationship, no matter how long the family was together prior, or how bonded they are. For many, that means the sudden and total cessation of contact. Sometimes, the agency arranges a final meeting, where the parent must try to explain to their child that this is the last time they will see each other, and why. Sometimes, they don’t get even that.

“My clinic worked with a father who had been visiting his son in foster care for years,” said Chris Gottlieb, co-director of the Family Defense Clinic at the New York University School of Law. “The child knew that was his father and was very attached to him. The boy was going to be adopted by a single mother. We asked—begged, really—for the father to be able to at least stay in his son’s life through continued visits after the adoption, but the agency refused. They wouldn’t even let the father say goodbye. Who could think that’s actually good for a kid?”

For me, I am still able to have continued contact because they are with their paternal grandmother—but she could rescind that privilege at any time. Once the adoption is finalized and the case closed, she could also, if she chose, give the girls back to me. In other words, the agency has given total power over my daughters to the very woman who made the allegations that triggered this case. The allegations which were found to be untrue at the trial, but had by then entangled me in a system that judged and misjudged my substance use disorder, PTSD and lack of financial resources.

The termination means that if my daughters are seriously injured, I can be barred from visiting them in the hospital. I have no say over their medical or educational decisions. I can’t travel with them without permission; I am forced every day to choose between staying with them in Florida, isolated from all my support systems; or returning to Seattle, Washington, where their older half-brother lives.

They call me “mommy” and “mama” and “mom,” but I am no longer their mother—not legally. The decision leaves them to build their personalities, attachments and aspirations atop a constantly shifting foundation embedded in grief and confusion—the opposite of what this system purports to secure for children. It leaves me navigating a lifetime of unending trauma and loss.

Perhaps worst of all is the knowledge that this outcome was arbitrary—an automatic reaction to a timed financial incentive set at the federal level.

Perhaps worst of all is the knowledge that this outcome was arbitrary. The decision to terminate my rights was not based upon any actualized threats to my daughters’ safety; rather, it was an automatic reaction to a timed financial incentive set at the federal level by the Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA).

Under ASFA, if states want to receive the funding that allows them to finance child protective programs, agencies must either return children home, or move to terminate parental rights once a child has been in out-of-home care for 15 of the past 22 months.

“ASFA has exceptions,” Gottlieb noted. “They don’t have to file a termination of parental rights on the [15/22] time-frame if there’s one of these exceptions, which include if kids are in kinship foster homes, or if for any reason it’s not in the child’s best interest to do the termination.” Since my daughters were in kinship care, the first of those exceptions applied in our case. I would argue the second does too.

“But,” Gottlieb continued, “the only message that gets emphasized is the simplistic rule that you have to file. People are not doing the case-by-case analyses they’re supposed to do to apply these exceptions.”

In my case, when we sat down for a required mediation session in March, the guardian ad litem attorney acknowledged my daughters’ bond to me, but felt that the financial benefits of adoption, including payments to their grandmother and funding for college, were important enough to warrant severing our legal bond.

Misunderstandings of Drug Use and Addiction

Another major issue throughout the case has been the misunderstanding and mistreatment of drug use and addiction. It began with the initial investigation, when an inexperienced member of the Broward County Sheriff’s Office came by the home while I was away and did not attempt to contact me, instead choosing to file for an emergency removal because she felt my history of engaging in methadone treatment was proof enough that any allegations against me were true.

It continued at the deposition, when the judge charged me with neglect and imminent risk of harm. She cited my “skill with language,” which apparently made me a less credible witness, and a discussion about marijuana with a family member that my in-laws testified about at trial as her reasons for the decision, in lieu of any actual instances of harm or near-harm to my daughters.

“Everyone is so focused on the substance use that often they don’t see, or refuse to acknowledge, a mother’s positive behaviors.”

It continued as the agency not only failed to provide me with referrals to the trauma and addiction treatment I was mandated to complete, but also barred me for months from accessing them myself—in part by forcing me to undergo a psychological evaluation, which they repeatedly delayed, before engaging in any other state-sponsored services. Throughout the life of the case, they never referred me to evidence-based treatment.

“Everyone is so focused on the substance use as this negative behavior that often they don’t see, or refuse to acknowledge, a mother’s positive behaviors,” said Mishka Terplan, an OB/GYN and addiction medicine physician who was retained by advocacy organization Movement for Family Power to provide expert testimony during my case.

“For you, the positive behaviors were, you … sought treatment on your own and you demonstrated motivation,” Terplan described. “You understood the importance of treatment; nobody had to tell you treatment was important, you actually had to tell them you wanted this. You actively sought it and when the program was not adhering to standards of care, you sought another program that would be better for you. That seems to be completely correct.”

But at the mediation, the representative for the state attorney’s office—a worker from the drug court division who was standing in because the case was undergoing yet another of many instances of staff turnover—summarized all of that as, “too little, too late.”

Then she leaned across the table and told me that before ASFA, parents with substance use disorders had an actual chance to get their kids back, but now with the timeline, it just didn’t work.

As Jerry Milner, the associate commissioner at the Children’s Bureau, co-wrote in an article published about a month after my rights to my daughters were terminated:

“The timelines in the [ASFA] … do not reflect what we know about treatment and recovery and do not reflect the contextual factors that are directly relevant to successful reunification, such as the availability of quality services and treatment and a family’s ability to access services timely and effectively. The decades that have passed and research lessons learned have revealed the timelines as lacking alignment with what many children and families need.”

Despite acknowledgments at both the state and federal level that the ASFA timeline does not make sense in the context of substance use, and despite admonishments from the medical and legal advocacy communities, agencies across the nation continue to file for termination of parental rights at the 15/22 mark, so that they can continue to receive the millions of dollars in funding it affords them.

They continue to do this even in cases like mine where they don’t have to. And in cases like mine where everyone is in agreement—at least behind the closed doors of the mediation room, where any statements made can’t be applied as evidence at trial—that the act of termination will, in fact, cause harm to the children.

If nothing is done, the consequences will continue to echo through my life, my children’s, and generations of my family to come.

And it has. It has caused my children harm. Not a day goes by that I don’t hear my daughters ask to come home to me, tell me they love me and miss me, muse about how much they miss Seattle, their brother, and their other friends and family back home. Their questions about the situation, their acknowledgment that it’s not normal and doesn’t feel good, are accumulating urgency with each passing day.

If nothing is done, the consequences of this travesty will continue to echo through my life, my children’s, and generations of my family to come. I started a petition requesting the immediate return of my daughters and/or an independent third-party review of my case and appropriate remedial action. It’s a small hope, one that rests upon the world taking notice and deciding to care, but it’s what I have left.

For all the families impacted by such systems, we can listen to the experts, and stop applying this irrational timeline. Our federal government can reform or repeal ASFA, and in the meantime, states have the choice to take a stand and say no—to take the hit instead of forcing their families to.

As Gottlieb explained, “Just as some states opt out of certain aspects of Obamacare, they could opt out of ASFA. They could turn down federal money rather than buying into a system that incentivizes severing parent-child relationships.” But so far, none have.

It’s millions of dollars, and it would cripple their child welfare system, but the other choice is continuing to tear apart hundreds of thousands of families each year for no real reason.

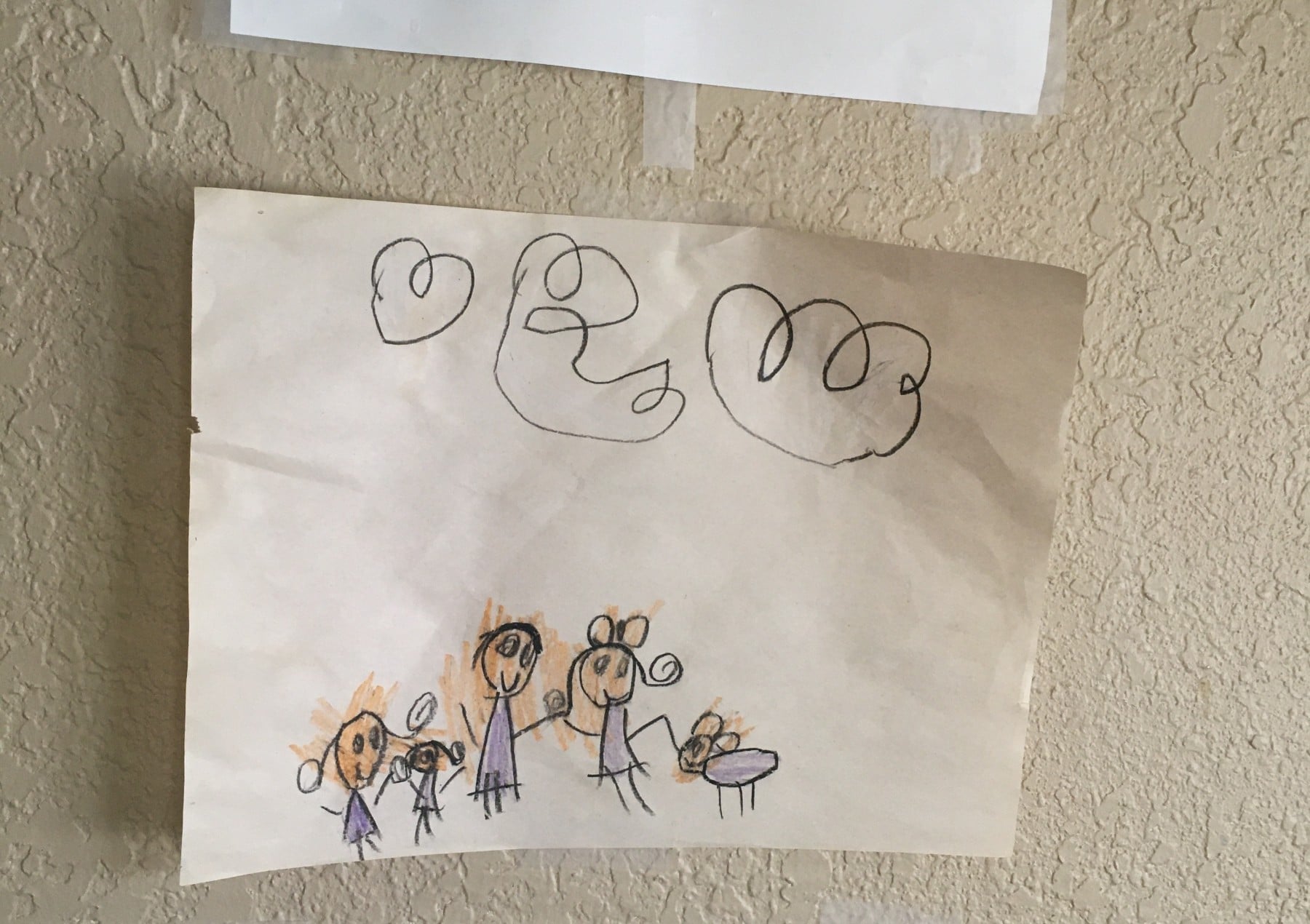

Yesterday I hung on my walls in Hollywood, Florida the sequined monsters and Dr. Seuss landscapes the girls and I crafted together over the holiday weekend. I was reminded of the conversation we had while we glued down those pom-poms and plastic gems, one about the strangeness of memory, and how we forget the memories we don’t use.

“Will I forget you, Mama?” asked my elder girl.

“Do you think about me?” I asked.

“I think about you sometimes,” she replied.

Then my littlest one chimed in. “I think about you. I think about you all the time. I think about you all the time because I’m always missing you so much.”

Photograph courtesy of Elizabeth Brico.

Show Comments