On September 26, Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell (D) unveiled his proposed 2024 budget. It indicates the city will not be prioritizing the most critical component of its new drug possession ordinance: diverting people to treatment and other jail alternatives before they’re arrested, rather than after.

On September 19, the Seattle City Council approved an ordinance criminalizing drug possession and public use as a misdemeanor. The legislation broadly lines up with the Washington State law enacted in July, but Seattle Municipal Code required that the city pass its own version before it could actually prosecute such cases. The ordinance gives unprecedented power to the Seattle City Attorney’s Office, which for the first time will have the authority to prosecute people for drug possession.

Though the ordinance covers “pre-booking, pre-trial and post-sentencing diversion,” it was approved without any accompanying funding. Harrell is expected to issue an executive order further clarifying certain logistics, but has not at publication time and did not reference it in his September 26 budget proposal speech.

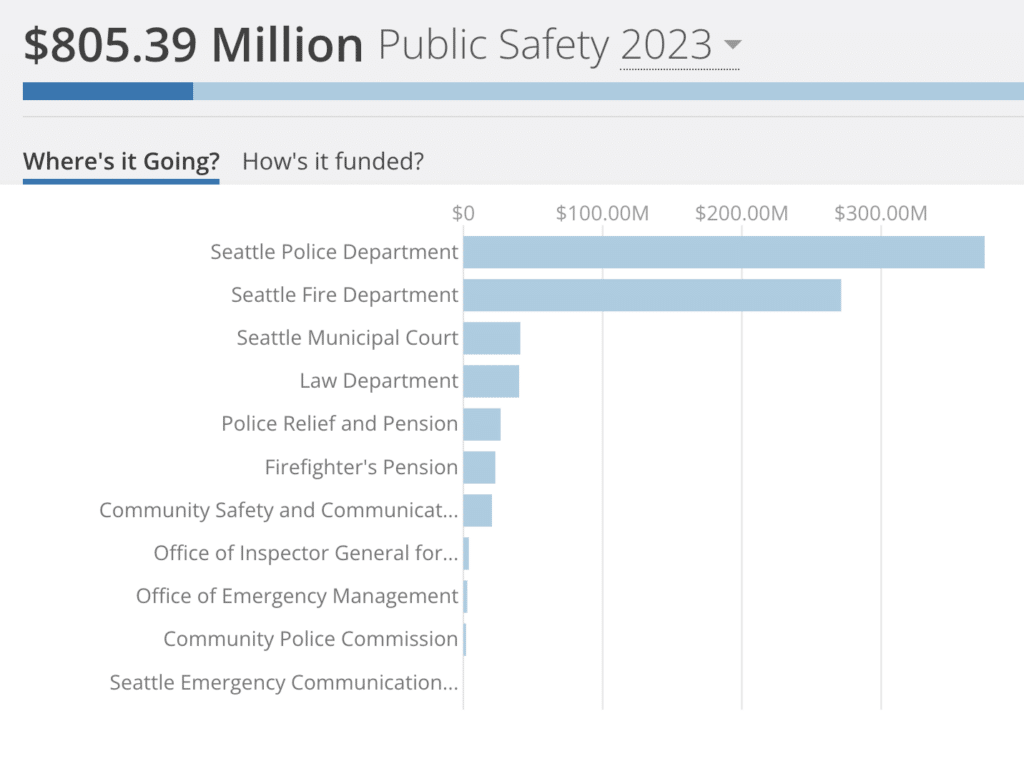

“We have a tool now we can use to help everyone in the city. To make this law effective, it requires reinvesting in diversion programs like LEAD. Our budget includes nearly $17 million toward [such] diversion programs,” Harrell said, to audience applause.

Let Everyone Advance with Dignity (LEAD, formerly an acronym for Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion) operates at the state level and is exclusively a pre-trial intervention, not a pre-booking one; in order for someone to be diverted to LEAD, they have to be arrested and charged first. Harrell did not cite any other funding for any other diversion programs.

“Applied right, that law will not only support safe, welcoming sidewalks and neighborhoods, it will prioritize diversion for drug users,” Harrell said, “keeping them out of the criminal-legal system and putting them on a path to getting well.”

Arresting and prosecuting people does not keep them out of the criminal-legal system.

Arresting people and prosecuting them in court does not keep them out of the criminal-legal system. It exposes them to law enforcement and saddles them with a criminal record that can bar them from jobs and housing. Just being booked and sitting in county jail for a few days—even if charges are later dropped or dismissed—can destabilize someone’s entire life, especially those living in poverty or hovering on the brink.

It also raises overdose risk precipitously, contrary to public statements by Seattle City Attorney Ann Davison that without the new ordinance, “overdose deaths are likely to continue to climb.”

On June 6, the first attempt to pass the ordinance failed due to concerns over lack of resources to support diversion to treatment. In response, Davison said she was “outraged” that the City Council did not advance the bill.

“Our buses, parks and sidewalks are filled with individuals who need help getting into treatment,” Davison said in a June 6 statement. “Seattle will now be the only municipality in the State of Washington where it is legal to use hard drugs in public. That means drug use on public transit and in our neighborhoods will continue unimpeded.”

It is not true that without that legislation, the City of Seattle was legalizing public use of substances like fentanyl and methamphetamine. Possession and public use of illicit substances were still criminalized under Washington State law, and the Seattle Police Department (SPD) retained its authority to arrest perceived drug users at its discretion; the resulting cases just fell to the county prosecutor, who handles felonies, rather than to Davison, whose jurisdiction is misdemeanors.

“The King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office has overseen prosecution of these kinds of cases for years. Because of that, it has clear policies about what cases they would charge, a functioning drug court already up and running and a plan for diversion and treatment,” Councilmember Lisa Herbold stated on June 7 in response to Davison’s claims.

“The Seattle City Attorney’s Office does not have this infrastructure [and has] not yet developed any policies around what the threshold would be for them filing charges against drug users, if they would use diversion resources to get people help or detailed fiscal projections for how much it would cost to increase prosecutions or incarceration.”

Herbold cosponsored the version of the ordinance that ultimately passed. It encourages SPD to refer people to treatment and assessment services rather than arrest them, but does not require it. Pre-booking diversion would come out of the city’s budget, and so with no funding allocated for that, most drug users will inevitably get funneled to pre-trial diversion, i.e. LEAD.

Police officers will decide who gets referred to services pre-booking, and who gets referred to Davison pre-trial. Davison will have the discretion to prosecute however many people she wants, but doing so means that the city has to figure out where to put them. It can use municipal jails, which are small, or pay per person per day to house people in county jails.

But if Davison opts to prosecute, that means that once the defendant is arraigned, the city can send the bill to the state regardless of whether it’s for incarceration or treatment.

It makes sense that the new ordinance was passed but not funded. Why would it be? Prosecutors are always going to prosecute; all that the city has to do to not spend money on drug users is arrest them.

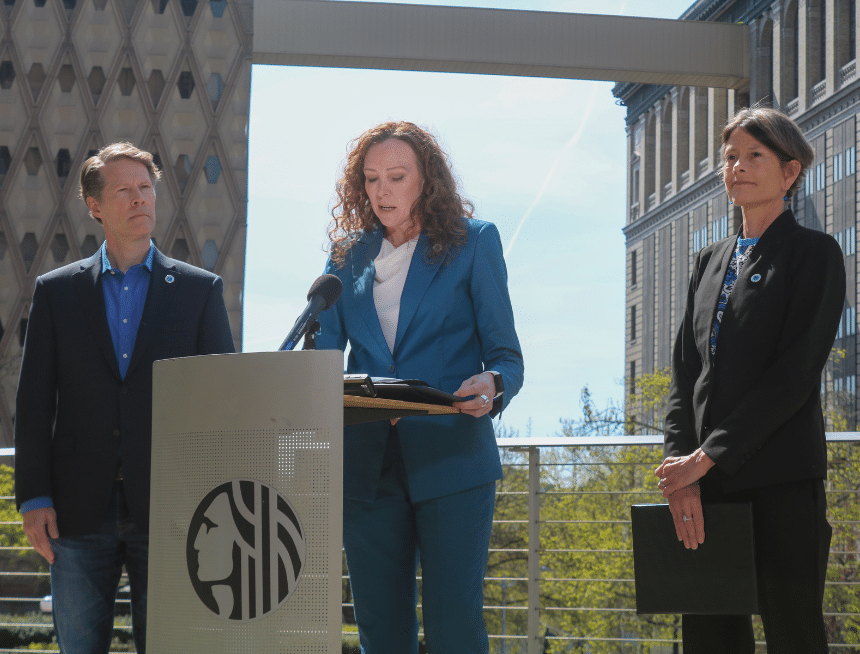

Top photograph of City Attorney Ann Davison via Seattle City Council. Inset graphic via Seattle Open Budget.