On April 23, Washington state lawmakers ended the current legislative session still in limbo over whether to increase penalties for drug possession, which for now is punishable as a simple misdemeanor. If some version of Senate Bill 5536 isn’t passed by July 1, the absence of any law criminalizing drug possession means it would technically become legalized statewide.

None of us incarcerated in Washington Corrections Center are holding our breath. Everyone who watched the news unfold late into the evening of April 23, including myself, expects the penalties to increase instead.

“[W]hat happened tonight was unacceptable,” Governor Jay Inslee stated after the legislature adjourned. “Decriminalization is not an option for me and it is not an option for the state of Washington. I expect legislators to deliver a solution.” Inslee will most likely to call a special session in the coming weeks, essentially putting the decision into overtime.

In 2021, the Blake decision struck down felony drug possession in Washington—but, rather than decriminalizing possession, instead made it a simple misdemeanor. That ruling sunsets on July 1. Without a replacement, jurisdictions across the state would be left to determine how to criminalize possession individually. This isn’t decriminalization the way anyone wants it; you could essentially be walking down the street, cross an invisible line you didn’t know was there, and find yourself subject to penalties you didn’t know were there either.

“In lieu of legal system involvement” doesn’t mean what it sounds like.

The most recent version of the wide-ranging SB 5536 would make possession a gross misdemeanor—or, as the joke goes, a “light felony.” Simple misdemeanors include charges like shoplifting, and are punishable by up to 90 days in jail. Gross misdemeanors include charges like fourth-degree assault, and can get you up to one year.

While the bill proposes increasing the punishment for possession, it also proposes increasing the options for avoiding that punishment. To reduce gross misdemeanor convictions, “law enforcement is encouraged to offer a referral to assessment and services available [arrest alternative programs] in lieu of legal system involvement.”

Sounds good, right? Here’s what “in lieu of legal system involvement” looks like:

An officer decides to arrest you for drug possession. You opt for pre-trial diversion. If granted, you’re taken for an assessment, which has to be conducted by one of three entities: recovery navigators; an arrest and jail alternative program (AJA); or a law enforcement assisted diversion program (LEAD).

Recovery navigators would in theory be people with lived experience at newly established programs intended for low-income people who use drugs. Your home jurisdiction might not even have one of these programs. If it does, the program might already be overwhelmed with a caseload that exceeds its allotted resources and funding. The remaining two routes are AJA, a grant-funded program that diverts people to one one of a small handful of recipients like Catholic Communities of Western Washington and local law enforcement departments; or LEAD, a national pilot program that as the name suggests is operated by law enforcement.

There are a lot of treatment programs in Washington; but the free ones are already full.

In earlier versions of the bill, people had the right to receive their assessment within seven days, as well as receive transportation to a treatment program within two hours of where they live. Those provisions are gone now. So the people who can afford lawyers will be able to go get a timely assessment, and are much more likely to end up with private treatment providers who treat them well. There are a lot of authorized treatment programs in Washington state; but the free ones are already full.

You can pass your pre-trial diversion program either by “successfully completing” treatment or by “having 12 months of substantial compliance”—whichever comes first. Or, if no treatment is recommended, you can fulfill the program with 120 hours of community service.

Everyone’s entered into a statewide database tracking the outcomes of pre-trial diversion routes. Updates are regularly submitted to the court. If you’re suspected of “noncompliance” at any time, then prosecutors motion for termination, you’re given a notice, and a court hearing determines whether you’re in violation of the program. Only the people in power would describe all this as something that doesn’t involve the criminal legal system.

I’ve been waiting for the outcome of this legislation for months. Despite the apprehension many of us share about this bill, I’ve held to the knowledge that if it passed, it also contained the following directive:

“Establishing a Safe-Supply Work Group. HCA must establish and staff a Statewide Safe Supply Work Group with members appointed by the Governor to make recommendations related to providing a regulated, tested supply of controlled substances to individuals at risk of drug overdoses.”

We don’t have internet access in here, and that version of the bill of from February. Turns out, the safe supply part was cut in early March. What remains in the current version are the harms.

From personal experience, I believe there would be officers who’d do their best to use pre-trial diversion equitably. I also believe this version of the bill would allow politicians to pat themselves on the back while in real life, they’ve deepened the criminalization and surveillance of people living in poverty.

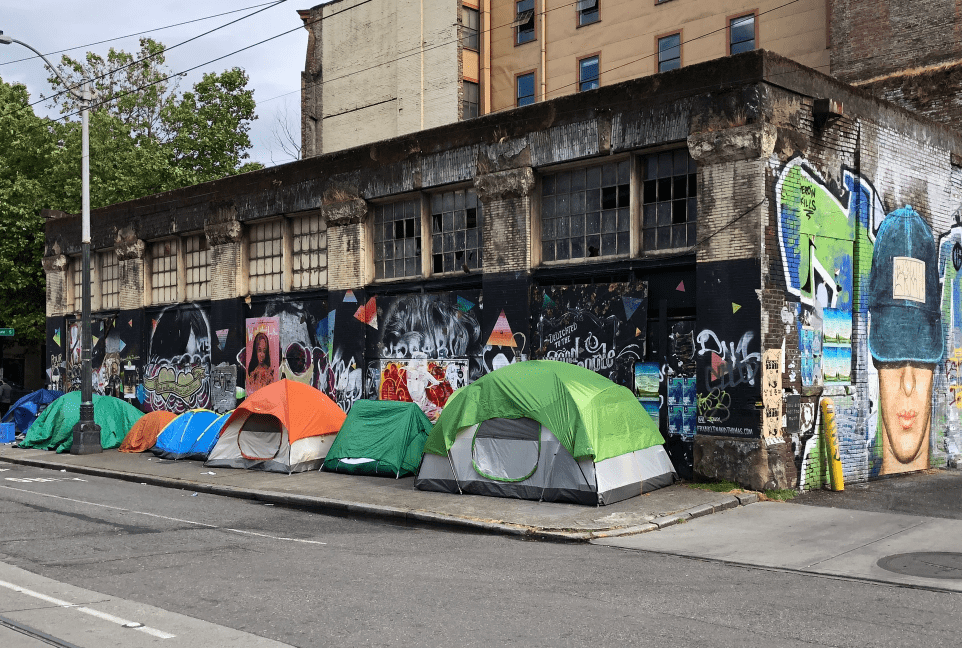

Those people will receive the slowest and least fair assessments, spend months under the thumb of overburdened, carceral-looking programs, have any behavior that belies the toll this takes on them reported as “noncompliant,” and still end up with the conviction in the end. Cops will have new ways to do what they already want to do: scoop up people from parks or tents or on the street and leave them somewhere else. And from the moment that happens to you, every so-called choice involves the legal system.

Photograph via Seattle Office for Civil Rights

Show Comments