Since 2018, the World Hepatitis Alliance has promoted World Hepatitis Day—July 28—with the hashtag #FindingTheMissingMillions. A global advocacy and awareness campaign, it was dedicated to the millions of people around the world living with undiagnosed hepatitis B or C. Now that the three-year campaign has reached its conclusion, for 2021 there is a new theme: Hepatitis Can’t Wait.

The pandemic prompted many government leaders and health organizations around the world to backburner efforts for issues, like viral hepatitis, that they considered less urgent—as if such crises would not be exacerbated by the pandemic and did not merit being addressed in tandem.

“With a life being lost every 30 seconds globally to viral hepatitis, even in the COVID-19 crisis we can’t wait for action,” Cary James, the World Hepatitis Alliance’s chief executive officer, told Filter.

In the year and a half since the pandemic began, more than 4 million people around the world have died of COVID-related causes. During that time, well over 1.5 million people are estimated to have died of causes related to hepatitis B and C. And yet, we see no headlines pointing to the latter crisis and few public acknowledgments of the dead. You won’t find people lining up for rapid antibody tests for hepatitis—because of the stigma still associated with it, as well as because of a scarcity of low-threshold services.

The priority populations for hepatitis—the people at highest risk for contracting and transmitting it—are often the same populations that are the most medically underserved across the board. People who use drugs, especially those who inject; people who are currently or formerly incarcerated; Indigenous people; men who have sex with men; immigrants.

“The people disproportionately affected by hepatitis are often those who are marginalized by societies and underserved by health systems,” James said. “Without equitable access to appropriate prevention, testing and treatment programs, hepatitis is allowed to devastate those communities.”

Hepatitis is not some unsolvable issue. Hepatitis B has a vaccine. Hepatitis C has a cure.

Hepatitis is not some unsolvable issue. It can be detected through basic tests that deliver results rapidly and require very little training to perform. Hepatitis B has a vaccine. Hepatitis C has a cure.

But often, we do not have the right stakeholders at the table—people with lived experience—making the decisions that determine the accessibility of testing and treatment.

“We cannot expect people to simply come to us for testing; the service needs to go to them where they are,” James said. “Peers … have a crucial role to play in supporting their communities.”

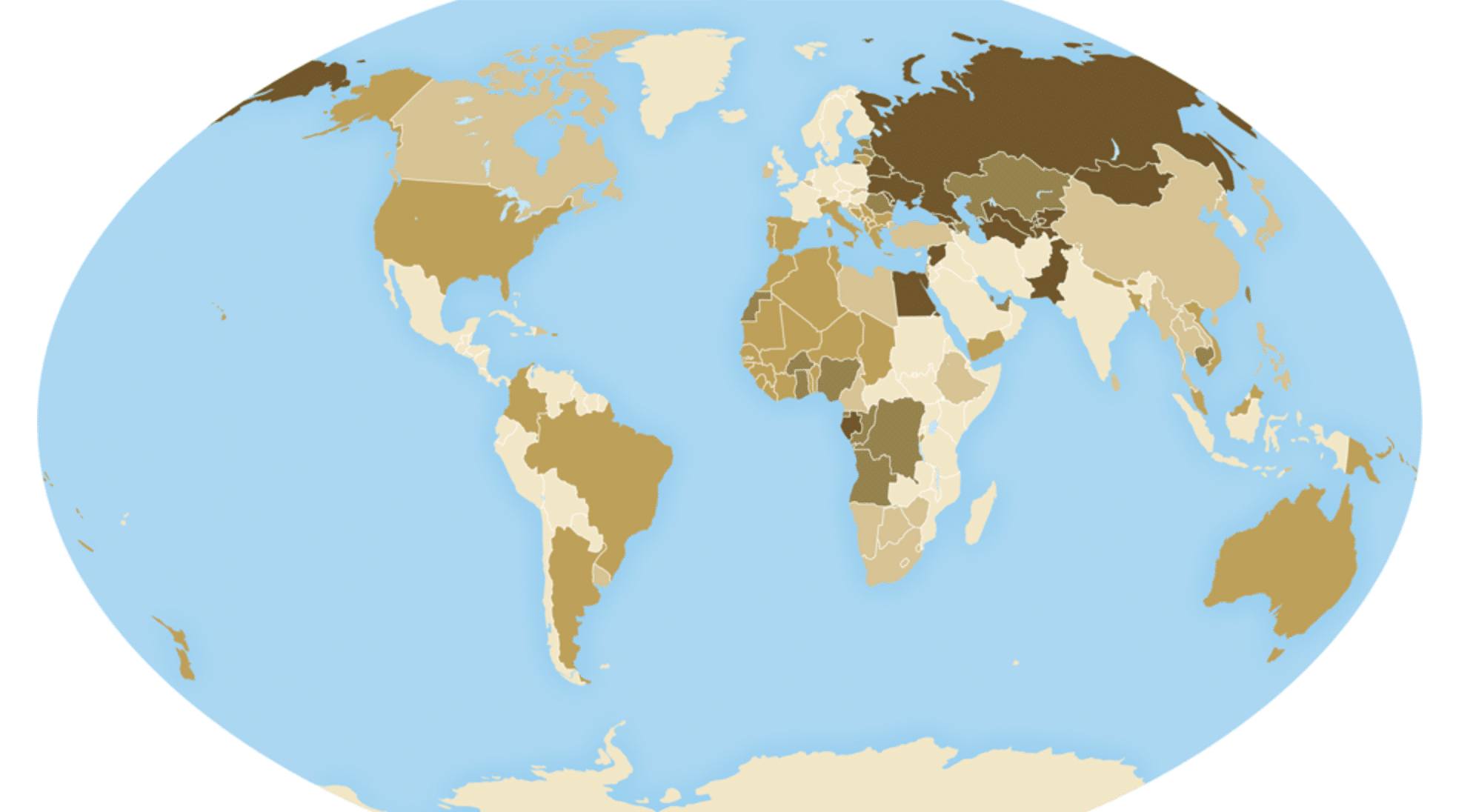

The World Health Organization goal of eliminating viral hepatitis B and C is defined as a 95 percent reduction in new cases of the former and 80 percent of the latter, with an overall 65 percent reduction in mortality by 2030. But only a handful of countries are on track to reach this goal.

“The common thread across all of these countries,” James said, “is a robust involvement of community organizations in the response.”

In Egypt, annual hepatitis C deaths had mounted to 40,000 by 2015—7.6 percent of total deaths in the country. But the nation bargained with medication manufacturer Gilead to lower the price of treatment, as well as setting up an online portal where diagnosed people could sign up to receive the treatment. It followed up with a nationwide screening program. Now, Egypt is on track to be the first country to reach the elimination goal—potentially as soon as 2023.

“In a short time, they screened over 60 million people [and] linked those that had hepatitis C to care,” James said. “This has been achieved due to a strong political will for action.”

But places like the United States and Canada lag behind. We know what works: low-threshold screenings and accessible treatment offered by harm reduction workers, including those with lived experience of hepatitis. We have the tools and the knowledge to reach hepatitis elimination by 2030. What we do not have is sufficient funding for, or education around, these tools. We do not yet have the strong political will.

The most urgent area we need to scale up, according to James, is testing. Nine out of 10 people living with hepatitis have not been diagnosed and are unaware of their condition. This means both that they themselves are not linked to care, and that they are at risk of unknowingly transmitting the virus to others.

So the next time you’re getting blood work done, ask the doctor if they can check for hepatitis. Or visit your local syringe service program and ask if they can test you, or refer you to another friendly harm reduction org that can. Hepatitis isn’t an issue that can be pushed aside. It’s one that cannot wait.

Photograph of global hepatitis C prevalence in 2020 via Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Show Comments