On May 27, 2020, the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease published a statement in anticipation of World No Tobacco Day: Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) should prohibit vapes and heated tobacco products (HTPs). Borrowing COVID-era vernacular, the press release said that “in an abundance of caution, the sale of these products should be banned in LMICs.”

It wasn’t a surprising stance. The influential NGO, headquartered in Paris and colloquially known as the Union, is meant to be “working to improve health for people” in LMICs. It receives substantial funding from Michael Bloomberg—the philanthropist and occasional politician who has dedicated billions of dollars to help enact draconian tobacco control measures across the globe, especially in Asia.

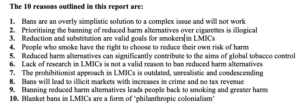

Now, the other side is firing back. On March 16, the International Network of Nicotine Consumer Organizations (INNCO)—a worldwide association of consumer groups from 33 countries that advocates for tobacco harm reduction—released a direct response to the Union. It outlines 10 reasons why banning e-cigarettes and HTPs in LMICs is ineffective—and also offensive.

“‘Quit or die’ cannot be the only alternatives we offer.”

Around 80 percent of the world’s tobacco users live in LMICs. They are not, as INNCO notes, “a homogeneous entity.” Indeed, one of the few things binding this diverse group of people and cultures is their governments’ hesitation or inability to resist the encroachment of moral-touting, monied Western interests like the Union.

“Individuals deserve to have awareness about, and access to, all options available to them, especially when their own health—and that of their families—is on the line,” Samrat Chowdhery, the president of INNCO, writes in the paper’s foreword. “‘Quit or die’ cannot be the only alternatives we offer them.”

INNCO’s 10 reasons to resist the Union’s demand might be bucketed into three categories: that prohibition-like methods haven’t worked for nicotine and only create illicit markets, as they have for vaping devices and e-liquids in the United States, India and elsewhere (“illogical”); that harm reduction, when it comes to tobacco, is a “valid” goal; and that blanket bans are paternalistic and reductive (a form of “philanthropic colonialism”).

“As the world is moving toward equality and parity, here comes a well-funded organization that says, while it’s OK in the West, people in the developing nations should not have access to these products,” Chowdhery told Filter. “They’re imposing their own will on these countries. This is the undercurrent.”

It’s still flowing. Look no further than Asia, where health departments are not unaccustomed to poor financial support from their governments, and, therefore, can easily settle on the one-shoe-fits-all approach encouraged by Western nonprofits and billionaires. Vietnam, another country with ties to Bloomberg’s charity, is set to fully ban vaping products and HTPs. It will be joining several of its Asian neighbors—like Singapore and Thailand—in passing such legislation. India has adopted its own form of vape prohibition over the past year as well, leaving its citizens to continually rely on popular yet riskier options such as unprocessed tobacco leaves (rolled into bidis) or gutkha (chewing tobacco).

“The Union could not have a more ridiculous and patronizing position than telling developing countries that they are incapable of regulating vaping products and should ban them instead.”

Recently, some government officials in the Philippines have also alleged that the Bloomberg Initiative and the Union have been illegally paying regulatory agencies to pass their stringent tobacco control agenda. (The allegations are a source of considerable irony when you consider that those same organizations dismiss the recommendations of public health experts with even the loosest associations to the vaping or tobacco industries—the implication always being that they’ve been paid off.)

“The Union could not have a more ridiculous and patronizing position than telling developing countries that they are incapable of regulating vaping products and should ban them instead,” said Clive Bates, a public health expert from the United Kingdom. “For a group that is supposed to be fighting cancer worldwide, the Union has some pretty weird ideas and will probably end up doing more harm than good.”

“Banning the low-risk nicotine products and forcing consumers to use high-risk ones is completely at odds with the history of public-health progress,” echoed David Sweanor, an adjunct professor in the law department at the University of Ottawa and an expert in the tobacco industry.

You could waste a lot of time wondering why it’s happening. Is it because policymakers don’t want to listen to consumers, the ones advocating for vapes, HTPs and snus, particularly when many tobacco and nicotine users are among the most marginalized members of society? Is it because there’s not a Michael Bloomberg type on the opposing team, a rich figure capable of understanding, like George Soros did with other drugs, the importance of supporting tobacco harm reduction activism? (Not that counter-philanthropy would be the ideal solution.)

Or is it because of the US, where attention has been primarily focused on the overblown youth vaping “epidemic” and the mysterious string of “EVALI” illnesses, widely and wrongly attributed to nicotine vapes, that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention eventually admitted is likely from a compound found in illicit THC cartridges? Too late; the image of the world’s most important area of harm reduction had already been ruined in the country with the most power and global influence.

Even if the United States is driving the anti-harm reduction agenda … the US is far from the main battleground. LMICs are where the vast majority of smokers live.

Now that an actual pandemic is here—and naturally, opponents of vaping have seized upon COVID, too, to try to advance their agenda—the manufactured one of 2019 seems so long ago. (“What ever happened with the mysterious vaping illness?” a mainstream science reporter tweeted the other week.)

But even if the United States is driving the anti-harm reduction agenda, even as states like Connecticut keep pushing for vape bans, the US is far from the main battleground. LMICs are where the vast majority of smokers, and people trying to quit, live. And the panic begun here has spread there. If you want to affect global tobacco control, you do it in LMICs.

Case in point: Another Bloomberg-backed group, the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids and its lobbying arm, the Tobacco-Free Kids Action Fund, spend a significantly more money abroad in LMICs than it does in the States. And ludicrously, the World Health Organization, an agency with a long history of accepting Bloomberg’s charity, has yet to embrace e-cigarettes as safer than combustibles.

But for all the forces ranged against tobacco harm reduction, influence is easier said than done. In the end, a Western strategy—prohibition and abstinence pushed by non-nicotine users flaunting their moral superiority—cannot practically work worldwide.

The informal economy of a country like India, where millions of street vendors sell nicotine, makes it a different proposition to the US, with its infrastructure of gas stations and vape shops, Chowdhery pointed out.

For Indians facing the ban, “What’s stopping them from—you know—walking down the road?” Chowdhery asked, rhetorically. “If regulation is hard to implement, how much harder is it to impose a ban?”

Photograph via Flickr/Vaping360/Creative Commons 2.0

Both INNCO and The Influence Foundation, which operates Filter, have received grants from the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World.

Show Comments