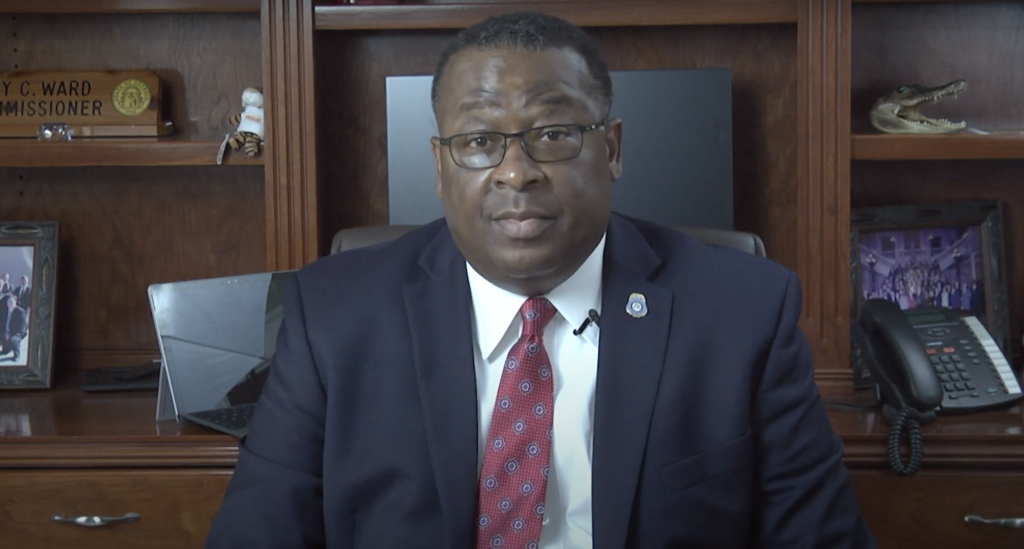

After four years at the helm of the Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC), Timothy Ward has stepped down. Though prisoners and advocates had long called for his removal, it didn’t happen the way many had hoped—on January 17, Ward was sworn into the State Board of Pardons and Paroles.

Ward’s tenure as GDC commissioner was appalling. He oversaw an understaffing crisis that resulted in unprecedented homicide and suicide rates, and then their investigation by the Department of Justice. He abandoned vulnerable prisoners—disabled, older, LGBTQ—to gang violence and medical neglect. Many are currently homeless, inside prison, because solitary confinement is a luxury now. He stood back as a new drug supply took hold of the system. He never pushed for conditional releases or meaningful decarceration, even when COVID took hold.

But his legacy goes beyond willful neglect. It is defined by a vehement war on transparency, one that should have disqualified him from a lateral move to a job granting pardons and paroles, and commuting death sentences. The Board did not comment on the reasons for Ward’s transition, other than to say he was appointed by the Governor.

COVID

Per UCLA Law’s COVID-19 Behind Bars Data Project, in September 2021 the COVID fatality rate in Georgia’s prison system was 2.4 percent—nearly three-and-a-half times the national average, and second only to Alabama’s. But Alabama’s COVID data were public.

GDC hasn’t publicized COVID testing or fatality rates since March 2021—before the Delta variant. That July, the department announced that its successful response made such reporting no longer necessary.

Speaking before the Georgia House Committee on Crisis in Prisons, UCLA data scientist Hope Johnson said GDC’s deliberate removal of transparency mechanisms was “almost certainly” concealing a higher fatality rate. It’s not as if prisoners stopped dying; GDC just stopped acknowledging them.

“[R]ather than improving the quality of their publicly reported data, the GDC has stopped reporting COVID-19 data altogether, making unfounded claims about the high rates of vaccination inside their facilities and among staff,” Johnson testified. “The culture of secrecy and resistance to oversight at the Georgia Department of Corrections presents a significant threat to public health and safety.”

Timothy Ward

Timothy Ward

Understaffing

GDC was facing an understaffing crisis since before Ward became commissioner in 2019, but the onset of the pandemic changed everything. Seemingly overnight, prisoners found themselves with just a handful of guards spread across their entire facility—fewer on nights and weekends. Since 2020, homicides inside GDC facilities have tripled.

Prisoners and their loved ones began pleading with Ward to call in the Georgia National Guard (GNG). The return of security personnel could mean the return of emergency medical services and transport to medical appointments, and above all a reduction in homicides and suicides.

GDC is not the only prison system to experience staffing shortages during the pandemic. States like Ohio, Florida, Montana, Indiana, Idaho, New Hampshire and South Carolina have brought in National Guard officers for exactly this reason.

“He acted as if the very suggestion was ludicrous.”

After Governer Brian Kemp deployed the GNG in Atlanta in March 2020, prison reform nonprofit Ignite Justice made several appeals to do the same within GDC. They went unanswered. In 2021, Ignite Justice Founder Emily Shelton raised the issue with Ward in person and recalls being assured “things are well in hand” and that activists need not concern themselves.

“He told me it was something he wouldn’t even consider,” Shelton told Filter. “He acted as if the very suggestion was ludicrous, and he rejected my organization’s detailed suggestions.”

In September 2021, GDC watchdog group They Have No Voice (THNV) called on Kemp and Ward to bring in GNG in a letter bearing 2,200 signatures. It, too, went unanswered.

At a GDC budget hearing in January 2022, Ward briefly acknowledged a staggering 49-percent turnover rate among new hires within their first year. THNV Founder Susan Sparks-Burns attempted, as Shelton had, to speak to Ward about deploying GNG. She too recounts Ward responding by telling her it was not up for consideration.

“COVID, homicide, suicide—all manners of death continued to rise,” Sparks-Burns told Filter. “I put that responsibility directly at the feet of Tim Ward.”

Low salaries don’t fully account for the turnover. Since the beginning of the pandemic, approximately 200 GDC employees have been arrested on work-related charges. At least 30 were arrested for battery or sexual assault. The majority have been corrections officers certified by the Georgia Peace Officers Standards and Training Council, which Ward continues to oversee.

Ward has been succeeded as Commissioner by Tyrone Oliver, the former head of the Department of Juvenile Justice and Department of Corrections who, in 2020, oversaw a 97-percent turnover rate. Two years later, well after the raises Oliver had claimed would fix things, the turnover rate was 90 percent. Oliver told state legislators in January 2022 that things were “trending in the right direction,” despite telling the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that same week that “we typically lose [most] officers before they get through the academy.”

Evasion and Obstruction

Since 2016, the Department of Justice has been investigating GDC’s failure to protect LGBTQ prisoners from recurring sexual and physical assaults by prisoners as well as staff. In September 2021, DOJ expanded its scope in response to the crisis of rising homicide and suicide rates.

Between May 2017 and December 2020, GDC issued at least 40 “Inmate Death Under Investigation” press releases. It no longer does this, forcing news outlets, watchdog groups and the federal government alike to litigate for vital information that should already be publicly available.

Ward simply continued to insist that GDC had many objections, but would not reveal what they were.

After first unlawfully—and unnecessarily—sending DOJ documents containing prisoners’ private medical records, GDC decided it wasn’t fair for DOJ to request documentation of prisoner deaths, and that it would only cooperate if the federal government signed an NDA. Meanwhile, GDC administrators were busy preventing site visits by media and lawmakers.

After he was served by DOJ, Ward filed for a protective order in an attempt to get out of handing over the subpoenaed documents.

Ward has insisted throughout the process that DOJ’s requests are too burdensome for an understaffed department like GDC. It’s telling that DOJ made repeated attempts to accommodate GDC’s lack of resources, even offering to lend its own personnel to help compile the documents, and GDC either rejected or ignored all of them. Ward simply continued to insist that GDC had many objections, but would not reveal what they were.

Perhaps Ward’s new position will suit him.

The five-member State Board of Pardons and Paroles is an entity unburdened by much oversight. Prisoners eligible for parole will wait years for their review, only to be told that, “due to the severity of your crime,” they had not served yet enough time. Years later, following their next review, they will be told the same thing again.

The Board does not conduct parole hearings. It’s not just that prisoners aren’t entitled to parole—they’re not entitled to any contact with the Board, to be able to view their own parole file, to any explanation for why they were denied parole or to any appeal of the decision. Perhaps Ward’s new position will suit him.

Top photograph via Pennsylvania Department of Corrections. Inset image of Timothy Ward via Georgia Department of Corrections.