One of the reasons we have Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for opioid use disorder (OUD) is that opioids are pretty straightforward. The difference between one opioid and another is meaningful to the user as a matter of personal preference, but from a pharmacological perspective they all basically hit your receptors the same way and produce the same set of effects; it just takes different amounts to get there.

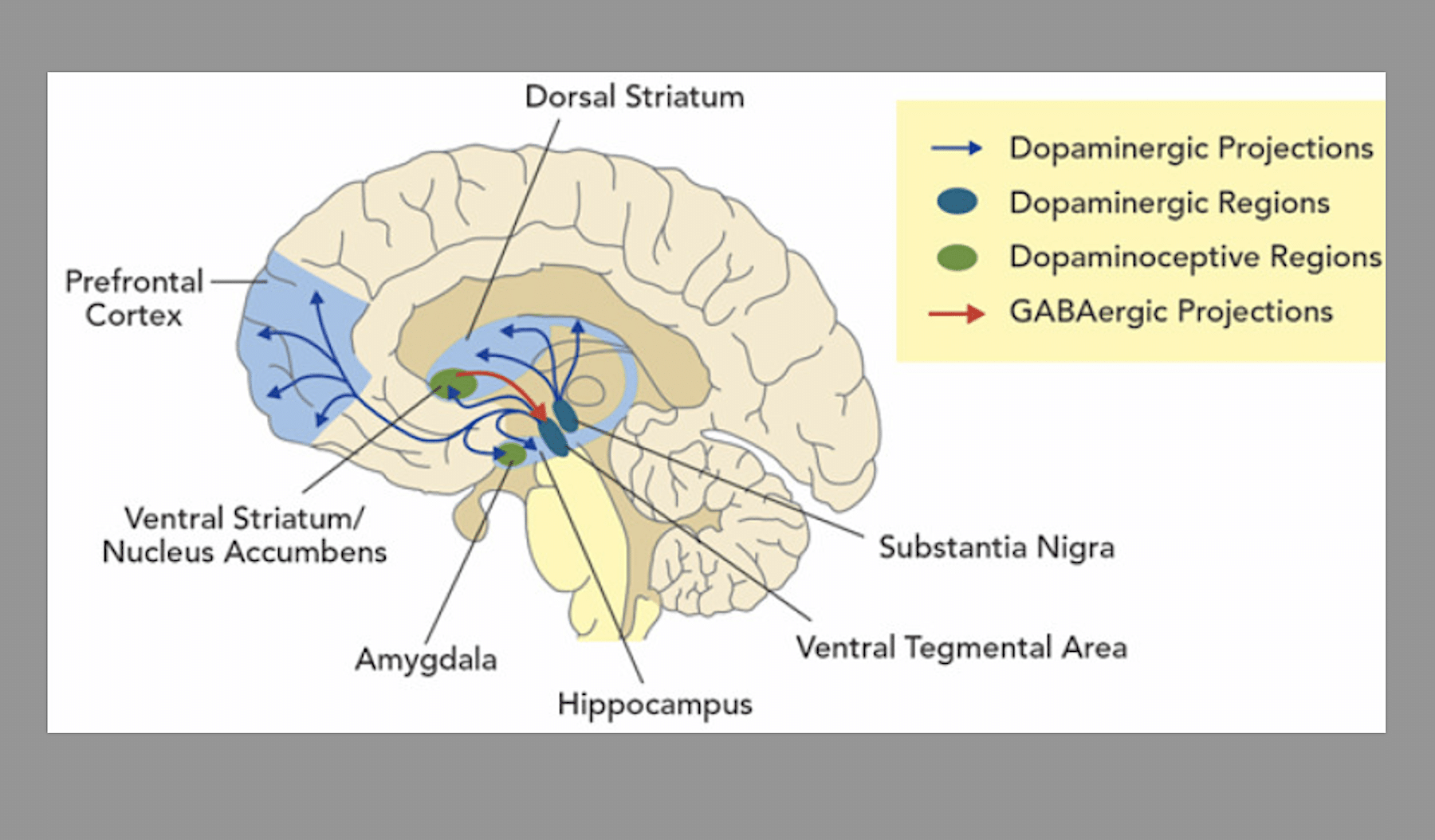

Stimulants are eclectic. Relative to opioids, they act on a greater number of different systems to produce a wider range of cognitive and physiological effects. Plus, the category encompasses drugs that have various different mechanisms of actions. They all act on your dopamine transporters, but dopamine intersects so many other pathways in your brain and body that it’s hard to pinpoint something for a medication to target.

Until December 4, the public can comment on the FDA’s draft guidance for the first medications for stimulant use disorder. Recommendations like this don’t carry any legal weight, but they do influence the direction pharmaceutical companies go in when developing something they’ll eventually need the FDA to approve.

On the whole, this guidance is actually the most thoughtful document on stimulant use I think I’ve ever seen from a federal agency. That does not mean it’s good, but it gets a lot of things right and that’s nice. You can submit feedback on the “Stimulant Use Disorders: Developing Drugs for Treatment” draft, publicly or confidentially, at this link or by mail.

Good News

“[W]hen evaluating the efficacy of a drug for the treatment of stimulant use disorder, the sponsor should consider studying people who use cocaine, methamphetamine and prescription stimulants separately.”

Cocaine lasts minutes; meth lasts hours, with most prescription stimulants not too far behind. Heterogeneity of stimulants—without even getting into the heterogeneity of how people use them—means they really can’t be approached in a uniform way, so any guidance on stimulant use that doesn’t start here has already wasted your time.

“This guidance does not address treatment of intoxication or poisoning with various stimulants or treatment of withdrawal from stimulants.”

Personally, I found this is one of the most reassuring parts of the whole thing. It encourages research and development of medications that don’t fixate on drug-war talking points like neurotoxicity, or OUD frameworks like mitigating withdrawal.

Some of the medications that come out of this will inevitably be in the vaccine genre, but they don’t have to be. The guidance encourages targeting symptoms based on disruptions to quality of life, but leaves things fairly open-ended in terms.

“Urine toxicology results (e.g., in reflecting pattern of stimulant use) are a surrogate measure because they are not a reflection of how the subject feels, functions, or survives … FDA does not, and has not, advised that the only appropriate endpoint based on urine toxicology results is the number of subjects achieving complete abstinence. FDA is open to other endpoints that reflect meaningful improvement.”

Abstinence, as determined by urinalysis, is the single outcome measure used by just about every treatment ever proposed for stimulants, and the FDA is right to de-emphasize it. The only other one that’s ever really mentioned is treatment retention, which the FDA correctly notes isn’t a useful metric in and of itself.

Bad News

“[C]ertain changes in pattern of stimulant use, such as fewer uses per day or reduced amount of drug used per occasion of use, are impractical to measure [and] likely unsuitable as clinical trial endpoints.”

The guidance suggests measuring changes in number of non-use days in a week, but not looking at changes in other patterns of use would make the scope of this research fairly narrow. People use stimulants for chemsex, to treat ADHD, to manage depression, to complement opioids, to go to work, to stay safe at night, etc. Urinalysis would often pick up substances used more than 24 hours ago, rather than on the day itself. So when measuring changes to non-use days per week would rely on self-reporting anyway, why not allow people to self-report other patterns of use?

Some people “binge” stimulants at night, or every few weeks or months. I use meth every day, from the moment I wake up to whenever it’s time to sleep. At the time of this writing—and this really does change constantly—the amount per use is either ~0.1 g or somewhere between ~0.03 g and ~0.06 g. The number of uses per day is like… between three and… 20? All of which comes out to consistent use of the same amount each day, if that makes sense.

“[S]timulants have the potential for single-dose lethality.”

This will never not be annoying. Literally anything has the potential for single-dose lethality, but that doesn’t mean it’s likely. Stimulant use comes with a long list of risks, and it misrepresents them to keep up this narrative of a lethal stimulant epidemic where you just use too big a dose and then die. Unfortunately the data making it seem that way come from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and it’s outside the FDA’s purview to fix that.

“FDA is interested in outcome measures … such as improvements in the ability to resume work, school or other productive activity, or fewer encounters with the criminal justice system.”

This was so close. The guidance already talks about the shortfalls of urinalysis or self-reporting, and there are few outcome metrics that are objective, humane and feasible to measure. Except criminal-legal system involvement, which is a fairly obvious one and which unfortunately only appears in the guidance as the one brief reference above. Stimulant users are constantly described as the greatest burden on law enforcement anyway; why not measure a treatment’s success by whether it helps alleviate that?

Image via National Library of Medicine