If you pay attention to the news, you’ve likely heard of naloxone, the medication that can reverse an opioid overdose. But naloxone (commonly distributed as Narcan) is not the only tool for overdose response, and harm reductionists are urging the public to be more aware of the vital technique of rescue breathing.

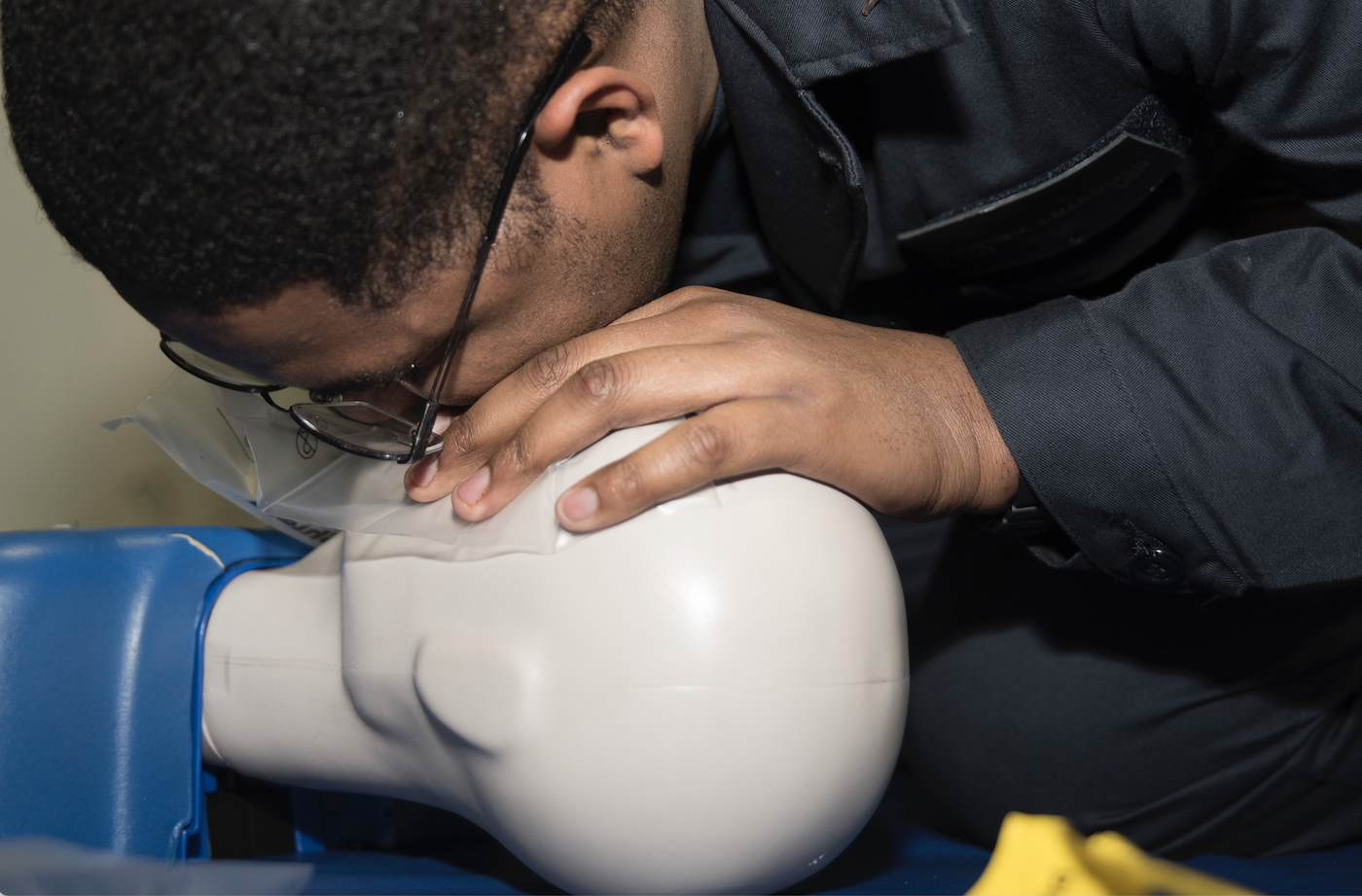

Rescue breathing involves repeatedly breathing into the mouth of someone who is unresponsive, until they are able to resume normal breathing. The need for this may last for just a few minutes or far longer, depending on various factors.

“The principle is that you’re breathing for the person while they can’t breathe for themselves,” harm reduction expert Dr. Mishka Terplan, medical director of Friends Research Institute, told Filter.

Opioids affect the part of the brain that regulates breathing, and an overdose occurs when the brain has essentially forgotten to breathe while a person is unconscious. When a person dies from an opioid-involved overdose, lack of oxygen is the cause.

Naloxone works to reverse this effect by knocking the opioids out of the brain’s receptors, which will eventually turn that part of the brain back on. It typically takes about 2-5 minutes.

“At every overdose response training I do, I explain that it is the most important part.”

But there are many situations—during the time naloxone takes to work, or if naloxone is not immediately available, or people don’t want to call 911—when rescue breathing can mean the difference between survival and death.

“At every [overdose response] training I do, I explain that it is the most important part,” Nick Voyles, executive director of the Indiana Recovery Alliance, a grassroots harm reduction organization, told Filter.

If necessary, he added, “you can rescue-breathe someone for eight hours until the opioid metabolizes.”

People can be revived with naloxone alone, but rescue breathing adds a crucial component in the interim by reducing the risk of brain injury—which can occur in as little as 3 minutes when the brain is deprived of oxygen.

Rescue breathing is also humane besides its ability to save lives. Because for people who are dependent on opioids, the mechanism by which naloxone can save a life—replacing the opioids in the brain receptors—can also lead to precipitated withdrawal, and a rapid onset of intense withdrawal symptoms.

Precipitated withdrawal can cause severe vomiting, diarrhea, chills, muscular pain, restlessness, agitation and panic, in addition to acute cravings for more opioids. It creates an additional risk factor of someone who has recently overdosed quickly seeking to use more opioids because they can’t stand the pain.

As a positive, evidence-based action after administering a dose of naloxone, rescue breathing can also mitigate the tendency to administer excessive naloxone.

All of this explains why overdose prevention centers (OPC) always have naloxone ready, but also employ strategies to minimize its use—including oxygen therapy as well as rescue breathing. OnPoint NYC, which operates two sanctioned OPC in Manhattan, reported that 83 percent of opioid overdoses in its first year of operations were resolved without the need for naloxone.

As a positive, evidence-based action after administering a dose of naloxone, rescue breathing can also mitigate the tendency—notable among law enforcement—to administer excessive naloxone. Multiple unnecessary doses can serve only to intensify a person’s precipitated withdrawal.

“The perspective of people who are not educated in naloxone and how it works in the brain, or often police or other officials, will just be that someone can’t overdose from [naloxone]—which they can’t—so you can give them as much as you need to until they wake up,” Courtney Peters, a board member for New Hampshire grassroots harm reduction group Insubordination Station, told Filter. “All that being technically true, the state that person wakes up in is going to be drastically different depending on how you handle the overdose.”

Naloxone will always be a critical tool, one that’s very easy for most people to use. And precipitated withdrawal is better than dying. But the addition of rescue breathing can help someone revive both faster and more comfortably. Harm reductionists view it as more crucial than ever before amid the continuing polydrug overdose crisis.

“There have been reports from almost everywhere in the country that their supply [of heroin or fentanyl] has been contaminated … most often by xylazine and benzodiazepines,” Peters said. Rescue breathing “is just basically trying to combat all of the substances that have been ingested, [including those] that are not opioids but are still going to depress your breathing or your ability to breathe.”

“If someone took what they thought was fentanyl, but it was really a tiny bit of fentanyl and mostly xylazine and benzos and other cuts, when you administer the naloxone, it could be working but the person is still not waking up because they’ve got so many other substances going on,” she continued. “Rescue breathing basically just buys you time for … this person’s natural ability to breathe to kick in.”

“If anyone else on my team had been the one there and not me, he would be dead or severely brain damaged.”

Keri Ballweber, a harm reductionist who has worked at and run both grassroots and conventional harm reduction programs in the Midwest, said she has found that some larger organizations do not always stress the importance of rescue breathing in their overdose response trainings. She has even worked on teams where her coworkers did not know how to rescue-breathe—a major oversight.

She recounted one overdose reversal situation in which she gave the person two doses of Narcan over eight minutes, and had to perform rescue breathing for 10 minutes before he regained consciousness.

“If I wasn’t breathing for him, he would be dead or severely brain damaged,” she said. “If anyone [else] on my team had been the one there and not me, he would be dead or severely brain damaged.”

Voyles has made similar observations. “This is what happens when you have watered down harm reduction,” he said. “We go places where this happens all the time, we have to retrain constantly.”

He also emphasized that rescue breathing, which can be done by anyone capable of performing the motions, is not the same as CPR, which involves chest compressions and can cause physical injury if done by someone who is not properly trained.

The National Harm Reduction Coalition website includes a step-by-step description of how and why to utilize rescue breathing when responding to an overdose. SAMHSA includes rescue breathing in its Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit for first responders. And Terplan is among experts who teach rescue breathing in all the overdose response trainings they conduct.

But despite this level of visibility, the grassroots harm reductionists who spoke with Filter said that they are not seeing rescue breathing implemented enough on the ground—particularly among first responders and staff of some of the larger harm reduction organizations.

“I think not only education is important, but also just trying to promote a culture where people can look at people who use drugs as human beings.”

Asked about a solution, Peters and Voyles agreed that it is necessary to increase education about rescue breathing among first responders and the general public, and also to reduce public stigma against people who use drugs.

“I think not only education is important,” Peters said, “but also just trying to promote a culture where people can look at people who use drugs as human beings, as human beings that deserve not only to be alive but not in horrible pain.”

Rescue breathing involves pinching the nose shut and breathing into the mouth every five seconds. Ballweber noted that while mouth-to-mouth breathing is ideal, it is also possible to perform rescue breathing by breathing into a person’s nose if their jaw is locked shut, which can sometimes happen during an overdose.

In certain circumstances, the modified jaw thrust maneuver (for which proper training is required) is recommended over the standard chin-tilt before commencing rescue breathing.

Terplan added that, “911 [operators] can walk you through rescue breathing and how to assess if somebody is breathing, which sounds simpler than it sometimes is in an acute situation.”

Here are the steps for using rescue breathing during an overdose, as written on the National Harm Reduction Coalition website:

1. Place the person on their back.

2. Tilt their chin up to open the airway.

3. Check to see if there is anything in their mouth blocking their airway, such as gum, toothpick, undissolved pills, syringe cap, cheeked Fentanyl patch (these things have ALL been found in the mouths of overdosing people!). If so, remove it.

4. Plug their nose with one hand, and give 2 even, regular-sized breaths. Blow enough air into their lungs to make their chest rise. If you don’t see their chest rise out of the corner of your eye, tilt the head back more and make sure you’re plugging their nose.

5. Breathe again. Give one breath every 5 seconds.

Photograph (cropped) by Naval Surface Warriors via Flickr/Creative Commons 2.0

Show Comments