Oregon has advanced a bill that would make naloxone more accessible to individuals and more affordable for harm reduction groups, among other distributors. On the March 6 deadline for bills to move out of the House, legislators voted 48-9 to send House Bill 2395 on to the Senate, with almost all Democrats and 14 Republicans in favor. Nine Republicans voted no, and three lawmakers were excused.

Though all states including Oregon allow residents to buy naloxone from pharmacies without a prescription, it is technically a prescription drug—though a formulation is likely to become available over the counter by the end of March. Oregon and Idaho are the only two states where the authority to dispense naloxone to individuals is left up to pharmacists. One of the bill’s provisions would allow Oregon to issue a standing order that would function as an umbrella authorization for pharmacies to dispense naloxone to people without prescriptions, rather than a more patchwork approach. Most states already have standing orders in place.

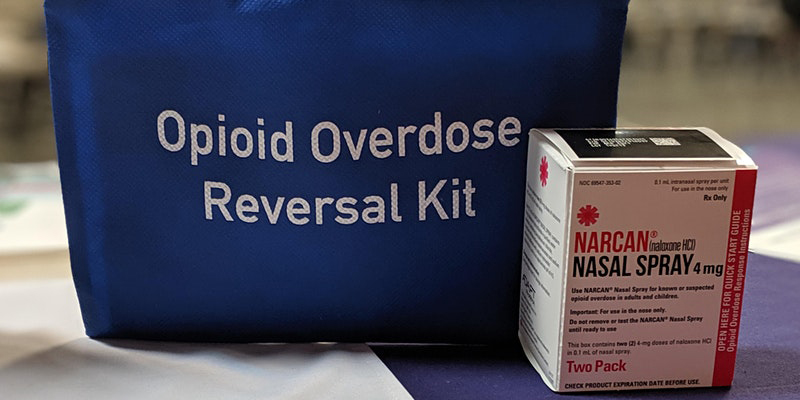

But relatively few people at high risk of overdose get their naloxone from pharmacies. And even if they live in proximity to a pharmacy that carries it, they may face hostility from pharmacists as well as the cost barrier of being charged $150 for a two-pack of brand-name Narcan. Community harm reduction groups, like syringe service programs, Remedy Alliance and NEXTDistro are the more critical sources. HB 2395 would allow the state to purchase naloxone in bulk, which could in turn increase the supply of naloxone accessible to community groups at lower rates.

“The statewide standing order will allow organizations to distribute naloxone [without] a big bureaucratic hurdle.”

“If you’re a program like mine that needs to order a lot of naloxone because we give out a lot, we have to order that through the drug distributors,” Haven Wheelock, the drug users health services coordinator at Portland-based group Outside In, told Filter. “The statewide standing order will allow organizations to distribute naloxone [without] a big bureaucratic hurdle.”

“Individual organizations and businesses who buy naloxone end up paying a lot more because they can’t use the purchasing power,” Wheelock said. “If the state is buying naloxone to distribute to organizations, it means we can order more with the same money. [If they] give me $500 I may only buy five or six kits, whereas that same $500 can get double that if we can order through the state.”

Oregon pharmacists and heath care workers already have authority to dispense naloxone at their discretion, but the bill would expand that to others, like law enforcement officers, firefighters and emergency medical responders.

The state’s “Good Samaritan” law already protected people administering and receiving naloxone from civil liability. The bill would add protections from criminal liability in those situations, but also remove liability for “failure or refusal” to administer naloxone, unless there is evidence of “wanton misconduct.”

Crucially, it would throw the weight of government support behind school employees who need to administer naloxone to students without written consent.

It would also protect owners of public-facing businesses who want to keep naloxone on-site, stored in such a way that it’s readily accessible to the general public. And crucially, it would throw the weight of government support behind school employees who need to administer naloxone to students without written parental or guardian consent.

“There’s been a lot of confusion in various school districts in how they can approach naloxone,” Julia Pinsky, executive director of the Oregon-based naloxone distribution group Max’s Mission, told Filter. “This will hopefully help them enormously; anyone in the school can respond to someone they think is overdosing, even without getting that parent’s permission.”

A separate provision would establish that under-18s could also receive outpatient diagnosis or substance use disorder treatment without a parent’s permission.

The bill would also amend Oregon’s “drug paraphernalia” laws to broadly exempt all equipment associated with drug use. Notably, this include glass pipes in addition to the more commonly exempted supplies like fentanyl test strips.

Photograph via Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services

Show Comments