To state the obvious, smoking kills. Tobacco smoking is the world’s leading preventable cause of premature death. Here in Nigeria, there are at least 11 million smokers, and despite declining prevalence, a fast-growing population means that the actual number of smokers is on the rise. This is especially true of young adults, connected in part to our growing nightlife culture.

The harms of smoking persist despite the efforts of anti-tobacco advocates in the country over the past decades, despite Nigeria being a signatory to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) since 2005, and despite the country’s adoption of the National Tobacco Control (NTC) Act in 2015. Nigeria suffers over 17,000 annual deaths as a result of smoking-related disease.

E-cigarettes were found by the UK’s Royal College of Physicians to be at least 95 percent less harmful than combustible tobacco, and by the US National Academic of Science, Engineering and Mathematics to be “far less harmful.” It has also been established that e-cigarettes are about twice as effective in helping smokers quit as other nicotine replacement products, such as patches or gum. Millions of people in the UK have already stopped smoking with the help of e-cigarettes.

But very few smokers in Nigeria are benefiting from this alternative.

Our organization, THRNigeria, recently conducted a small survey of Nigerian smokers in Lagos, our largest city. Of the 76 respondents, 87 percent said that they smoke daily; 67 percent would like to switch to the sole use of a less harmful product, while 52 percent wanted more information on these products.

Besides a lack of information, there is one major barrier to smokers switching to e-cigarettes in Nigeria: price.

If more smokers are to be encouraged to take up e-cigarettes and other less harmful products, it is necessary not only to proliferate accurate information on these devices, but to ensure that they are easily accessible across the country. Besides a lack of information, there is one major barrier to smokers switching to e-cigarettes in Nigeria: price.

As a recent market survey illustrated, the high cost of e-cigarettes compared with traditional cigarettes here restricts their use, and is the most likely reason for smokers not to switch. The more expensive and difficult one product is to access, the more likely people will use the other.

THRNigeria’s online survey reflected this: More than 60 percent of the current smokers reported that they would reduce or quit smoking if there were a significant reduction in e-cigarette prices, or if the products were more easily accessible.

Cigarettes are consumed differently in Nigeria compared to countries like the United States. Purchasing single cigarettes is the dominant way of obtaining them—and has remained so, despite our National Tobacco Control Act making this illegal in 2015. The accessibility of single cigarettes through informal sales from corner shops and kiosks drives experimentation and use among underage smokers.

Nigerian smokers buy between two and five cigarette sticks a day on average. The very low cost of a single cigarette means that smoking is accessible to everyone.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, of Nigeria’s six geopolitical regions, smoking prevalence is highest in the North-Central region—comprising the states of Kogi, Niger, Benue, Kwara, Plateau, Nasarawa and the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja. The South-South region, which covers the states of Akwa Ibom, Cross River, Bayelsa, Rivers, Delta and Edo, comes second. Prevalence in these regions is impacted by factors including armed strife, higher rates of substance use disorders, lack of adequate social support systems and unemployment.

Nigeria has seen a small but growing market for e-cigarettes over the last five years, yet prices have never been reduced—nor is there easy access to these products, due to a lack of market penetration and public awareness.

If we are to avoid catastrophic harm, it is vital that we find a way to make e-cigarettes as readily and cheaply available as their combustible counterparts.

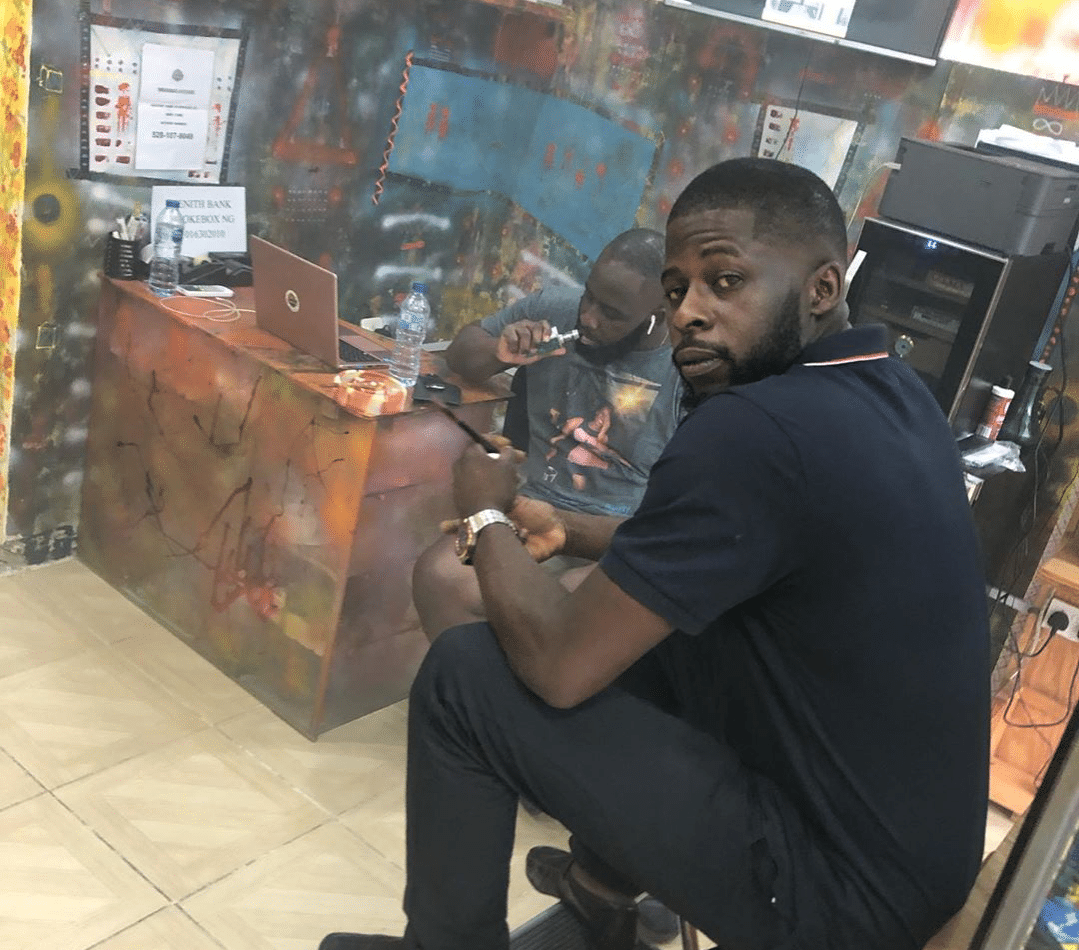

Having visited different vaping stores in Nigeria, I found that a vape-pen starter pack is sold for an average of $15 (N5,400), both online and in walk-in stores. A “mod” device of 40 or 120 watts goes for $47 (N16,920) or $121 (N43,500) respectively, while a pod device goes for $61 (N22,000). A 10 ml e-juice container is $10 (N3,600), while pod cartridges are $38 (N14,000).

For context, the “living wage” in Nigeria is $119 (N43,200) per month, according to Trading Economics.

Cigarette packs sell for $1.25 (N 450) on average—and are sold in far more locations than e-cigarettes. Given the relative costs and accessibility, it is little wonder that smoking remains far more popular than vaping.

If we are to avoid catastrophic harm to Nigeria’s fast-growing population, it is vital that we find a way to make e-cigarettes as readily and cheaply available as their combustible counterparts.

A collaborative effort by policymakers, manufacturers and public health agencies—both to lower the costs of e-cigarettes and to widely communicate their relative health benefits to smokers—would be the best way to achieve this.

Sadly, continued neglect of this vital issue by the Nigeria Ministry of Health and other public health agencies has done nothing to help poor Nigerians who are struggling to quit tobacco. Accurate training for our public health workforce on the relative benefits of vaping is sorely lacking.

That is why our organization steps in to create direct relationships with nicotine consumers in Nigeria, increasing and sustaining awareness on tobacco harm reduction—not just for urban areas, but also for rural communities across the country with high smoking rates. We plan to increase capacity building and effective training by organizing regular forums, workshops and social events to influence smokers who are struggling to quit, helping them to switch to a safer alternative.

Photographs courtesy of @smokeboxng, a vape shop in Lagos, Nigeria.

The Influence Foundation, which operates Filter, has, like the author, received funding through a Knowledge Action Change scholarship.