“Hey buddy, wake up.” My father gently gripped my shoulders and shook me back and forth.

I tucked my face into my chest and rolled in the yellowed sheet. Crisp edges of cigarette burns scraped against my skin.

“C’mon, please get up.”

I peeled my eyes open, only to be blinded by the digital alarm clock flashing, in fluorescent green numbers, “03:00 AM” over and over again, as it did every Monday morning. It continued to buzz, vibrating violently against the wooden dresser.

“Dad, turn it off,” I whispered, afraid that chips of wood would fly at my face.

“Can you pee for me, buddy?”

“I really don’t wanna.”

“I can’t come back hot, buddy, you know that. I’ll lose everything. If I don’t get my medicine, you know I’ll get super-sick.” He paused and grabbed my hand. “They’ll take me away from you.”

“Dad, I just don’t get it.” I tugged nervously at a loose thread on my pajama pants.

“Buddy, I need my other meds. They help me get moving in the day. They help me feel good, so I’m able to take care of you and Mom.”

“Well, why don’t you just tell your doctor that you need them?”

“He won’t listen. They just don’t understand. They think they’re bad—that we shouldn’t be on anything but what they give us. But they don’t know what it’s really like. They don’t know how hard it all is.”

I filled it up the whole way, just to be safe. “Here, Dad.”

I sat quietly.

He pulled out an empty pill bottle from his back pocket and put it on the bed. “Can you please just do this for me?”

“Okay, okay.” I took the pill bottle and started walking down the hall and into the bathroom. He followed close behind.

“You think you can fill it up about half-way for me?”

I filled it up the whole way, just to be safe. “Here, Dad.”

He twisted a cap on, put it back in his pocket, grabbed my hand and walked me downstairs.

My mother was kneeling on the floor, smearing brown eyeliner on the outer corners of each eye into little wings. She was dressed in her nicest clothes: her embellished Miss Me jeans, a striped Old Navy sweater and a large, faux fur-lined coat. Her curls were full, cascading down her back. She turned toward us, revealing perfectly lined lips and bronzed eyelids.

“I think Mark’s here. Everyone ready to go?”

We zipped up our coats, stepped out into the cold, made our way to the car, and began our two-hour journey upstate to one of the only clinics in Blair County, Pennsylvania. We’d done this each and every Monday for what felt like my entire life—all seven years of it.

It was hard to believe there was a time when we had to go up there every single day.

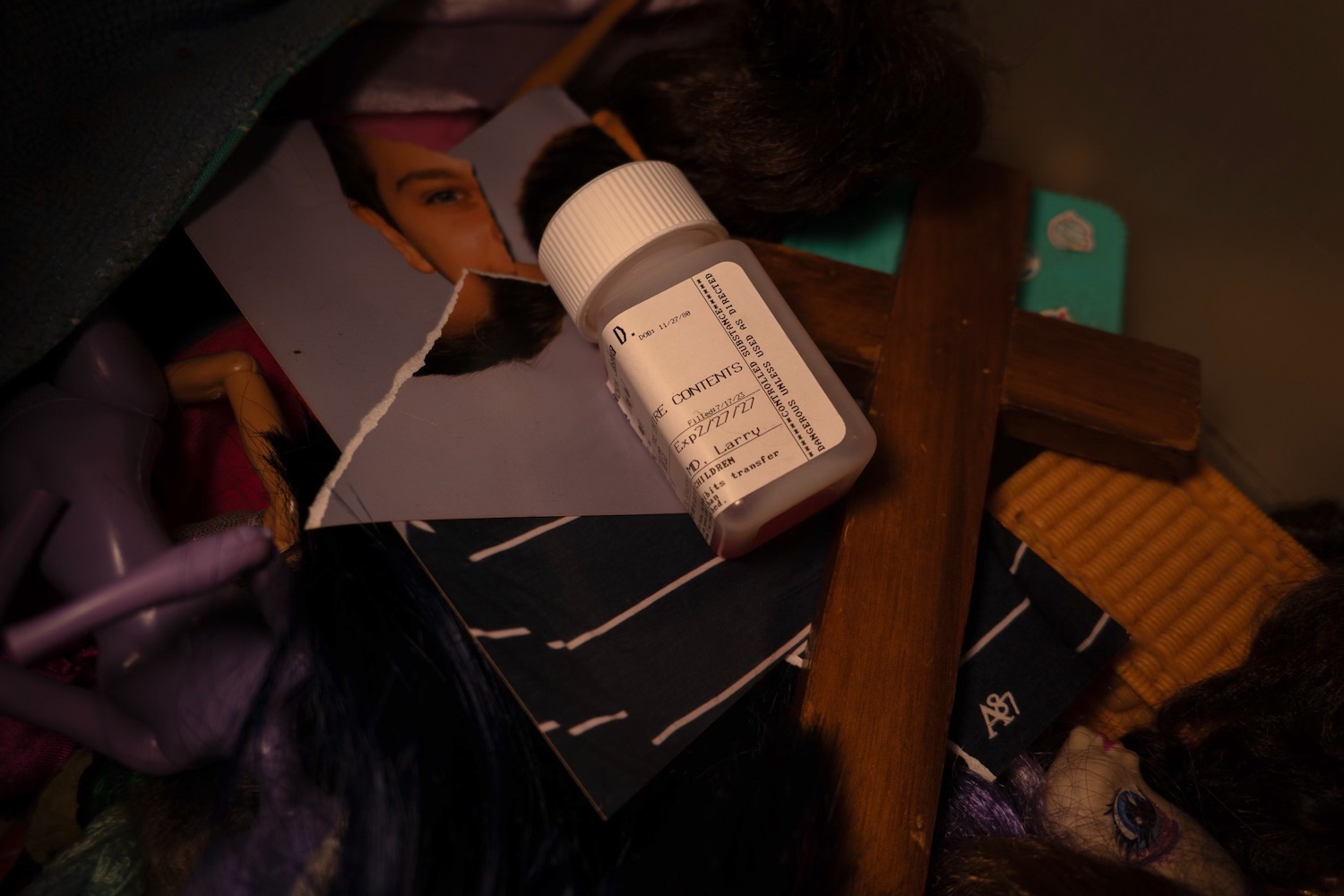

The author holding methadone bottles as a baby

I sprawled across the back seat and watched the snow fall into the valley off of I-99. I nodded in and out of sleep, picking up chuckles, soft melodies of Nirvana and 311, and stories of high school parties and drunken campfire accidents—of the “good old days” before Oxy, prison, probation and clinics.

I knew we’d made it when the car began to rock, as the tires fought against the gravel of the parking lot. I groaned as I stepped out and was met with fierce gusts of wind. My Spiderman PJs did their best to protect me against the cold.

I followed behind my parents as they made their way to the end of the line, near the bottom of the metal ramp that wrapped the exterior of the building. Dim overhead lights revealed foggy breaths and sharp, anxious movements.

The wait was long. I stared at folk in line until they’d begin to stare back. Voices and stories melted into one another.

“Isn’t it funny that this is supposed to make me normal—going to this place.”

“I can’t stand waiting in this fucking line any longer. It’s too damn cold to be out here like this. It’s like they don’t even see us as human,” one older man muttered.

“Why ain’t anybody movin’ up?”

“Please tell me you got you some xannies. They cut my dose.” The plastic from a small sandwich baggie reflected light into my eyes.

“C’mon let’s go!”

“This shit’s killing me, and they know it. They just want the fucking money. But I guess I’m the idiot who’s waiting in line at the slaughterhouse, huh.” Nervous chuckles followed.

“Isn’t it funny that this is supposed to make me normal—going to this place,” a woman said. “How am I supposed to be normal when I’m standing out here in the freezing fucking cold every day—and I’m missing work most of the time to do it! If I lose my job, I’m gonna lose the kids. This is a fuckin’ nightmare.”

“I’m never getting out of this. I’m gonna keep coming back to this line until I die.”

Once we made it indoors, I ran over to the play area with the other kids. I fought to grab any toy I could, then sat on the matted carpet and watched my mother and father continue to file through the line.

Eventually, my father reached the plastic, bulletproof border, where he was greeted by the nurse on the other side. He handed over his take-home box.

“Okay, looks like you have your urine today, so let’s go test ya.”

My father turned back. But he had forgotten to tuck the empty pill bottle back in his pants.

The nurse stepped into the main lobby, handed my father a large cylinder cup, and waved his hand toward the bathroom. “Just follow me into here.”

My father stepped inside, positioning himself, as he later told me, to avoid the direct gaze of the nurse. He carefully pulled the pill bottle out of where it was tucked in his pants, and began to pour out my urine, trying to mimic the flow of urination into the test cup.

My father turned back. But he had forgotten to tuck the empty pill bottle back in his pants.

The nurse looked down at the bottle, then back up at my father, with a disapproving glare.

My father handed the urine test back, fearful of what the nurse would say.

“I saw your kid out there. Don’t let me catch you again.”

The nurse waved him out of the bathroom, walked back behind the plastic border, pulled out his dose and handed it over.

After he swallowed it, the nurse signaled him to open his mouth, carefully checking to see that he swallowed every last drop. The nurse then filled his take-homes and slid his box across the counter.

“Next!”

My father walked over to me. He picked me up and pinched my cheek. He grinned as he whispered, “Thanks, buddy. I love you.”

I hugged him back. “I love you, too.”

Photographs courtesy of Aden McCracken

Show Comments