Many people living with HIV who pass through Washington Corrections Center (WCC) tell me their status, because I’m known as the guy to ask: How do I get through my prison sentence with HIV? I answer them as best I can, while wishing there was someone I could ask the same thing.

When I first became incarcerated during the AIDS epidemic, it was a time when everyone told you that having HIV meant you were going to die; often they were right. Over the past 28 years, I’ve learned that my status is not a death sentence. But without internet access or any connection to anyone else willing to talk openly about their status, I’ve learned almost nothing about what the HIV harm reduction movement looks like on the outside.

Washington Corrections Center tests new prisoners for HIV during intake—frequently without telling them. I believe an “opt-out” approach is more effective in these situations than “opt-in,” but I also believe in informed consent. I still recall the conversation I had some years back with a man reeling from having just been told he had HIV, when he hadn’t even known he’d been tested.

The Washington State Department of Corrections staff who provide comment to journalists are not accessible from prison-issue tablets. WDOC did not respond to a Filter editor’s request for comment.

You can’t exactly go to administration and say, “I’m breaking the rules—can you help me do it safely?”

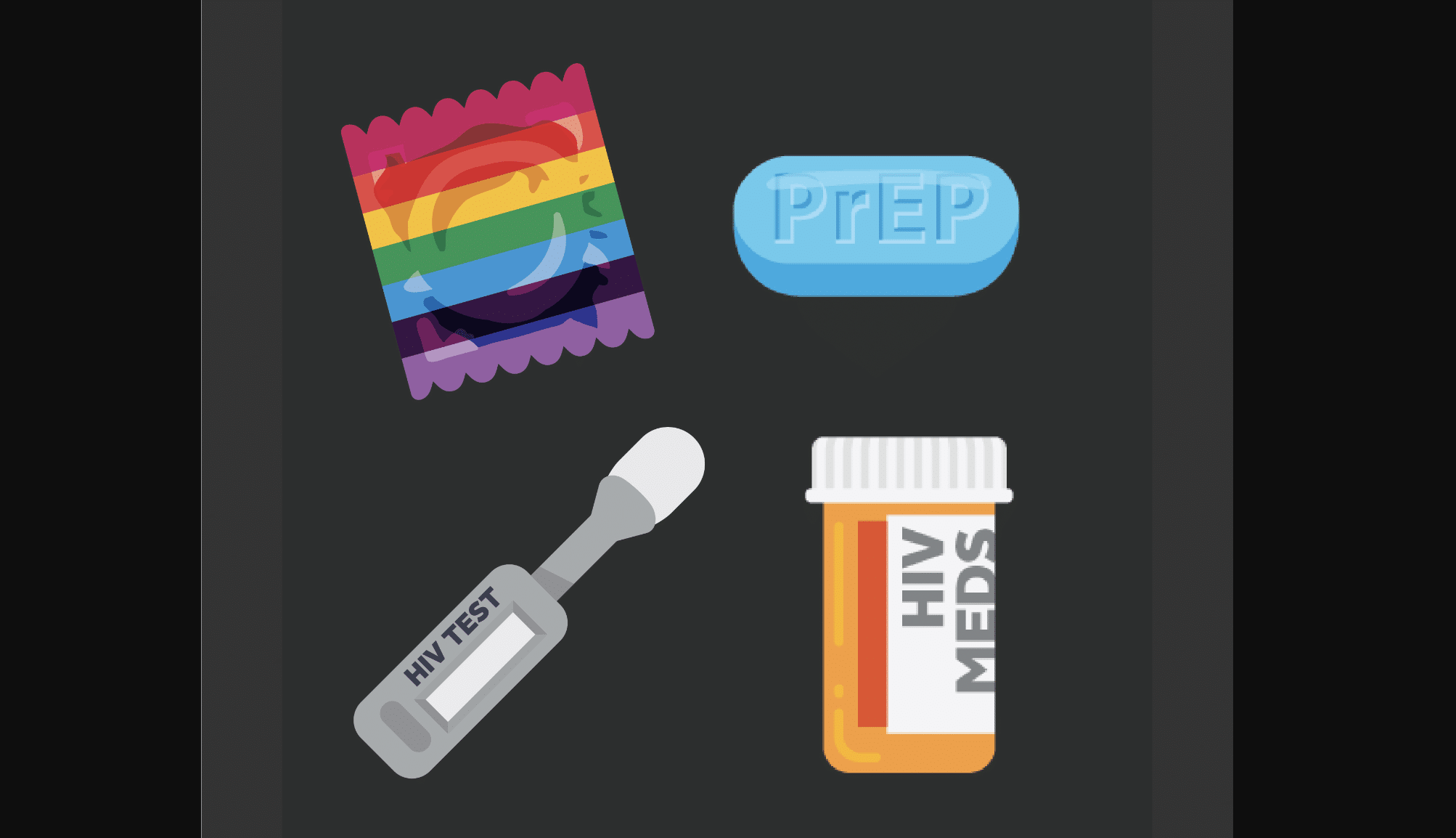

Antiretroviral medications are available to us in prison, and the confidentiality around getting them has improved somewhat over the years. Treatment is accessible; it’s prevention that’s illegal.

Safer injection in prison is a different concept than on the outside. Here it has little to do with sterile syringes, because there are none. I see on the news that syringes are often criminalized in the free world. Condoms and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) are not legal for us, because legally we can’t consent to sex. Safer sex resources would be invaluable to many prisoners, especially those who do sex work, but you can’t exactly go to administration and say, I’m breaking the rules—can you help me do it safely? Washington is one of the only four states to allow prisoners conjugal visits, and of course for these rare visits the state finds it appropriate to offer condoms.

People who’ve been sexually assaulted are eligible to receive post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), but getting it is not a low-threshold process. You can’t just discreetly tell medical staff you were assaulted and ask for PEP, you have to formally report it. The administrative burden alone discourages people from pursuing PEP, on top of which they may fear retaliation for reporting the assault.

As a concept, PrEP is stigmatized for the same reasons as booty bumping—the fear of being associated with being gay, which can make someone a target for violence regardless of their actual orientation or their ideology. In my early days of incarceration, when AZT was still the standard, people would decline it because it broadcast to the world that you had HIV, and on top of that that everyone would assume you were gay, too.

Multiple queer men have told me, unequivocally, that if they could take PrEP in prison they would. Many had been taking it in the free world. The system cuts off access at the same moment it locks them in an environment where HIV prevalence is disproportionately high.

When people are sharing a syringe, I suggest privately that anyone with HIV or hep C should go last.

When I know someone is at high risk, whether due to shared needles or sex work or being targeted for assault, I counsel them to request an appointment through the infectious disease department, which is free. Going through medical requires a $4 copay, and many wouldn’t access for this reason.

Often a few people will gather to share one syringe between them, and I can find ways to suggest privately that anyone with HIV or hepatitis C should perhaps go last. Not the greatest options, but I’ve been there, too. I encourage people to flush their syringes with water multiple times in addition to using bleach, which people sometimes presume is more effective at killing viruses than it actually is.

I’ve spoken about HIV stigma repeatedly at prison events over the years. The only opportunity I had to speak publicly was in a 2015 training video for medical providers. I told the interviewers that prisoners with HIV didn’t have any kind of community support, and that we’d benefit from being able to talk to other people with shared lived experience. Not much has changed since then.

This is the at-risk population, here. It’s us. All the same people who get outreached on the street, who inject drugs and engage in sex work, they all pass through here. That’s our prison-industrial complex. We lock people in the environments where the tools to prevent blood-borne disease transmission are taken away, and then we cycle them in and out of the general population indefinitely. If prisons and jails are the holding pens for people living with HIV, why doesn’t the HIV harm reduction movement reach us?

I’m nearly three decades into my sentence, and in that time I’ve only had two friends who were also living with HIV. Both were in the free world; one is dead now. I’m glad to have harm reduction knowledge I can share with people here, but it’s lonely work. I wouldn’t do it alone if I had the choice.

Show Comments