For her 700-plus page magnum opus on the history of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) New York, Sarah Schulman spent 18 years conducting hundreds of interviews and at least three years writing it all up.

But Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993 is not only the story of one of the most successful activist groups in American history. The just-published book is also a guide to understanding how ACT UP achieved so much change so quickly—and offers instructions for today’s activists on how to attain similar results.

Founded in New York in 1987, ACT UP still has chapters around the world and is an extraordinary model of activism by people with lived experience.

Schulman, a playwright, novelist, author and the co-founder of the Lesbian Avengers, was a member of ACT UP herself during the period she covers. I spoke with her about ACT UP’s accomplishments and what they can teach us.

Maia Szalavitz: You write early in the book about why some people become activists and others don’t. One of the things that struck me was that so many of them seemed to tell you something like “Well, I couldn’t not do it.” What did you conclude about what makes an activist?

Sarah Schulman: I was interested in, what do these people have in common inside ACT UP? Because they were so different. And at first, I thought, well, maybe they all came from childhoods or families who are community-oriented, but that did not pan out. And then I thought, well, maybe they’d all had particularly transformative experiences with AIDS. But that was not true either.

It’s the kind of person who can’t be a bystander.

People joined who didn’t know anyone who had AIDS. And in year eight, I interviewed Rebecca Cole, who at that time was an apolitical actress who had gotten a job at the AIDS hotline because she needed the money.

And she got a phone call from a woman in Connecticut who couldn’t get into a drug trial, because they didn’t accept women. And when Rebecca called the CDC and made an appointment with them and went with a friend and met with them—well, this is the beginning of the women with AIDS movement.

So, I was like, “Okay, this is a personality type.” I realized that it’s characterological, not experiential. Because of course, there were people with AIDS themselves who never did anything. So, it’s the kind of person who can’t be a bystander.

What would you class as the major successes of ACT UP?

ACT UP forced the Food and Drug Administration to restructure the way drugs were approved so that they would be available to people who needed them, even if they hadn’t gone through the approval process.

ACT UP won a four-year campaign to get the CDC to change the definition of AIDS to include symptoms that affected only women. And this change not only got women benefits, but it allowed women to get into experimental drug trials. Today, every woman with HIV who takes these drugs benefited from that.

ACT UP transformed the way that the world saw people with AIDS.

ACT UP won needle exchange in New York City. They started the movement of housing for homeless people with AIDS. And ACT UP challenged the Catholic Church [New York’s Cardinal O’Connor had inserted his religion into policy debates, opposing sex education in public schools and in particular, a curriculum that accepted LGBTQ rights. He also spoke out against syringe programs and condom distribution].

They also won the acceptance of a campaign called Countdown 18 months that was run by a 17-year-old girl, Garance Franke-Ruta. It restructured how researchers approached AIDS, going from looking for a medication that would cure AIDS to [focusing on] treating opportunistic infections.

And ACT UP transformed the way that the world saw people with AIDS and how they saw queer people and how they saw themselves.

It’s incredible how much ACT UP got done—and the impact it had on people with medical disorders becoming involved with research and treatment of those conditions.

I think [that] originally comes from the feminist women’s health clinic movement of the 1970s. Women were doing self-exams, physical exams, and that probably comes from the illegal abortion network.

And it’s why I say that reproductive rights was very influential [in ACT UP].

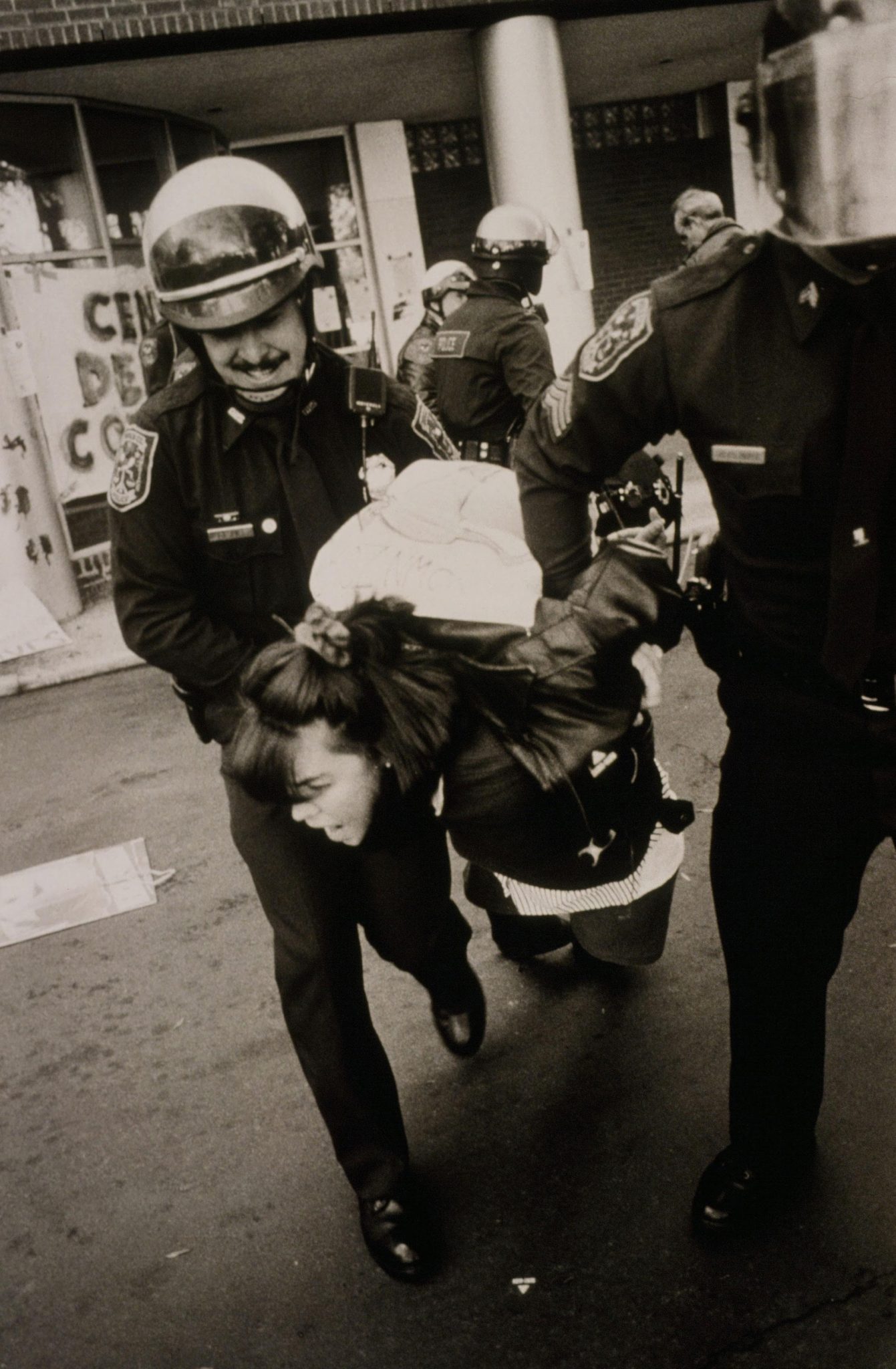

Tracy Morgan being arrested at the CDC in Atlanta, Georgia, on January 9, 1990. Allan Clear, who took the photo, was arrested shortly after.

Why do you think needle exchange as an accomplishment of ACT UP was so ignored by the media and by other writers and documentarians?

Everything that ACT UP did was ignored except for treatment activism. Why? Because there’s this idea in America: the John Wayne, the white male hero who triumphs as the individual hero. And drug users are not viewed that way, even though there’s a lot of overlap.

It took a long time to convince the world to stop looking at what category you were in and start looking at your behavior regarding AIDS. They didn’t think that white gay men use needles and they didn’t think that homeless people had gay sex. There were very racist and class-based lines. And that was influential in the way that history was written.

Yeah, I was absolutely astonished when I set out to write my harm reduction history [Undoing Drugs, to be published on July 27] that no similar book had previously been published. There’s not even a real history of needle exchange. These things get ignored.

One of the things I really liked about your book is that you were also looking at what made ACT UP successful. Please say a bit about that.

There were a lot of things. The central issue, I think, is that ACT UP did not work on a consensus model. That was one of its great contributions. So, if you wanted to do needle exchange, for example, needle exchange was very controversial at the time. You have to understand that David Dinkins was the city’s first Black mayor and he was really afraid of needle exchange, because powerful people [across racial and political lines] opposed it.

The only principle of unity was “direct action to end the AIDS crisis.”

In fact, the first thing he did when he got elected was shut down the city’s experimental exchange program.

That’s right. So you know, ACT UP was always fighting the disease plus City Hall. Still, there were people in ACT UP who were not supportive of needle exchange. But because ACT UP was not a consensus-based movement, it really didn’t matter. Whoever wanted to work on it, could work on it.

The only principle of unity was “direct action to end the AIDS crisis.” So even if people didn’t understand needle exchange, if they didn’t support it, they just simply wouldn’t work on it. There was no mechanism for stopping people from doing things. And that’s very important and a contemporary movement could learn a lot from that.

I think of Occupy Wall Street, which didn’t seem to learn from that.

Well, they didn’t have demands. I mean ACT UP was a reform movement, not a utopian movement. It was made up of people with a terminal disease. They had concrete demands based on the needs of people with AIDS.

I think that concreteness was enormously helpful because they did seek specific things, like “We want treatment for opportunistic infections, not for the virus itself.”

That took a reconceptualization. Because at the beginning Pharma was recycling failed cancer drugs that they had the patents for. And so, everyone was looking for the pill that [eliminated] AIDS. But it took a more sophisticated reconceptualization to see that [because] AIDS is an umbrella term, kind of like cancer. It’s not one thing. And it manifests differently in different people and requires different treatments. And so, going for the opportunistic infections is an evolution of thinking about how to approach AIDS treatment.

And it also kept many people alive long enough for the effective anti-HIV drugs to be invented. What else do you think made ACT UP so successful?

The other factors were direct action—not theory, and not social services. So that was very important. And just the idea of radical democracy, that you have a framework which recognizes that people can only be where they’re at. And this facilitates people responding in a place that makes sense to them, instead of trying to force the homogeneity of analysis or strategy or even language. And that was very crucial.

It always amazed me how many people in ACT UP who were positive lived. And you kind of wonder if the activism itself helped them live longer?

Well, I will say that that’s true for men. Every HIV-positive woman in ACT UP has died. Women had a completely different experience. Women couldn’t get benefits [like housing and Medicaid], they couldn’t get experimental drugs. They were sicker before they were diagnosed. They often came from poverty backgrounds. So, they did not live. But for the most part, people in ACT UP had access to cutting edge information.

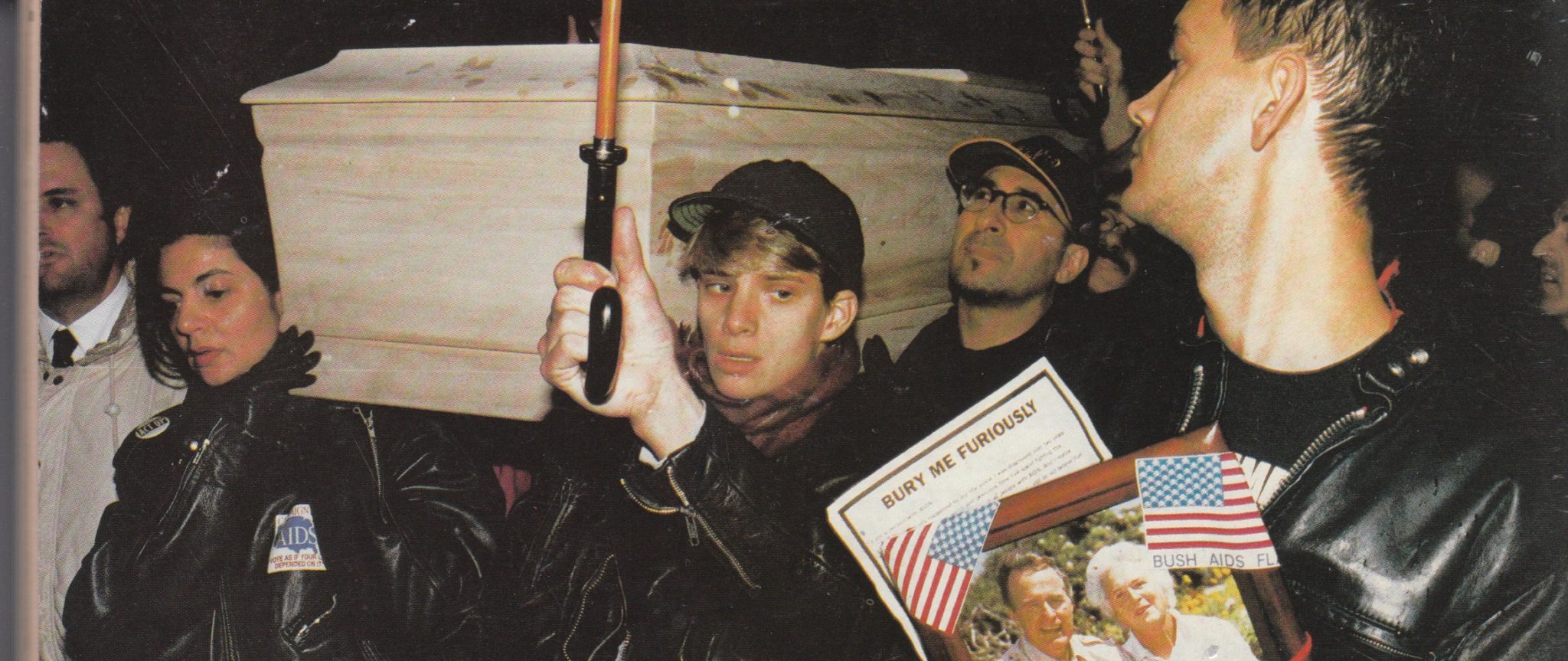

Mark Lowe Fisher’s funeral. From left to right: Tim Lunceford, Joy Episalla, BC Craig, Vincent Gagliostro, Scott Morgan, Eric Sawyer (partial). Photographer unknown.

How did ACT UP decide that, basically, if you didn’t agree with something, you didn’t have to do it, but you wouldn’t stop others who wanted to do it.

It was never decided. ACT UP did not theorize itself. And its message just evolved organically and wasn’t debated. ACT UP never said, “Oh, we’re gonna let everyone do what they want to do.” It just happened that way.

It seems that our best approach is a big-tent, radically democratic movement that does not demand conformity.

So many people were sick, so many people in ACT UP died in ACT UP, that the idea of controlling each other seemed like a waste of time. For example, at the beginning, there was a rule that you shouldn’t vote unless you’ve been to three meetings. It was never policed. Or, famously, they would say somebody needs to write a letter to the police commissioner or something. And somebody would say, I’ll do it, and then they would just do it. Nobody would read the letter. It wasn’t this type of micromanaging.

What would you say are the most important things that activists now could learn from ACT UP?

Right now, because so many people are under attack and because of economic inequality and racism, there are huge numbers of people who want profound transformation in this country. It seems that our best approach is a big-tent, radically democratic movement that does not demand conformity. And that people are encouraged to work in like-minded small groups that stand shoulder-to-shoulder with each other in a larger way. I think that any kind of movement that tries to force people to use the same words, or have the same analysis, those movements historically fail.

I guess that can make a lot of people right now nervous because of all this supposed “cancel culture”?

I don’t know. It’s interesting, because, for example, if you look at the St. Patrick’s event in 1989: So ACT UP had voted to do a silent die-in [where people lay on the floor as if dead]. And we went to the cathedral intending to do a silent die-in because that’s what we had negotiated. Then, Michael Petrelis jumped up on a pew and started screaming at Cardinal O’Connor, “You’re killing us, you’re killing us! Stop it, stop it!”

Total chaos ensued. People were screaming. There were dogs. There were police. It was crazy. Afterwards, people were angry with Michael because he had gone against the group. But no one suggested kicking him out of ACT UP. Because we didn’t have a self-concept of being a dominant culture as a group. It was very oppressed people—even white gay men in that period were profoundly oppressed. In order to kick someone out, you have to have a sense of yourself as powerful. But that concept just simply didn’t exist.

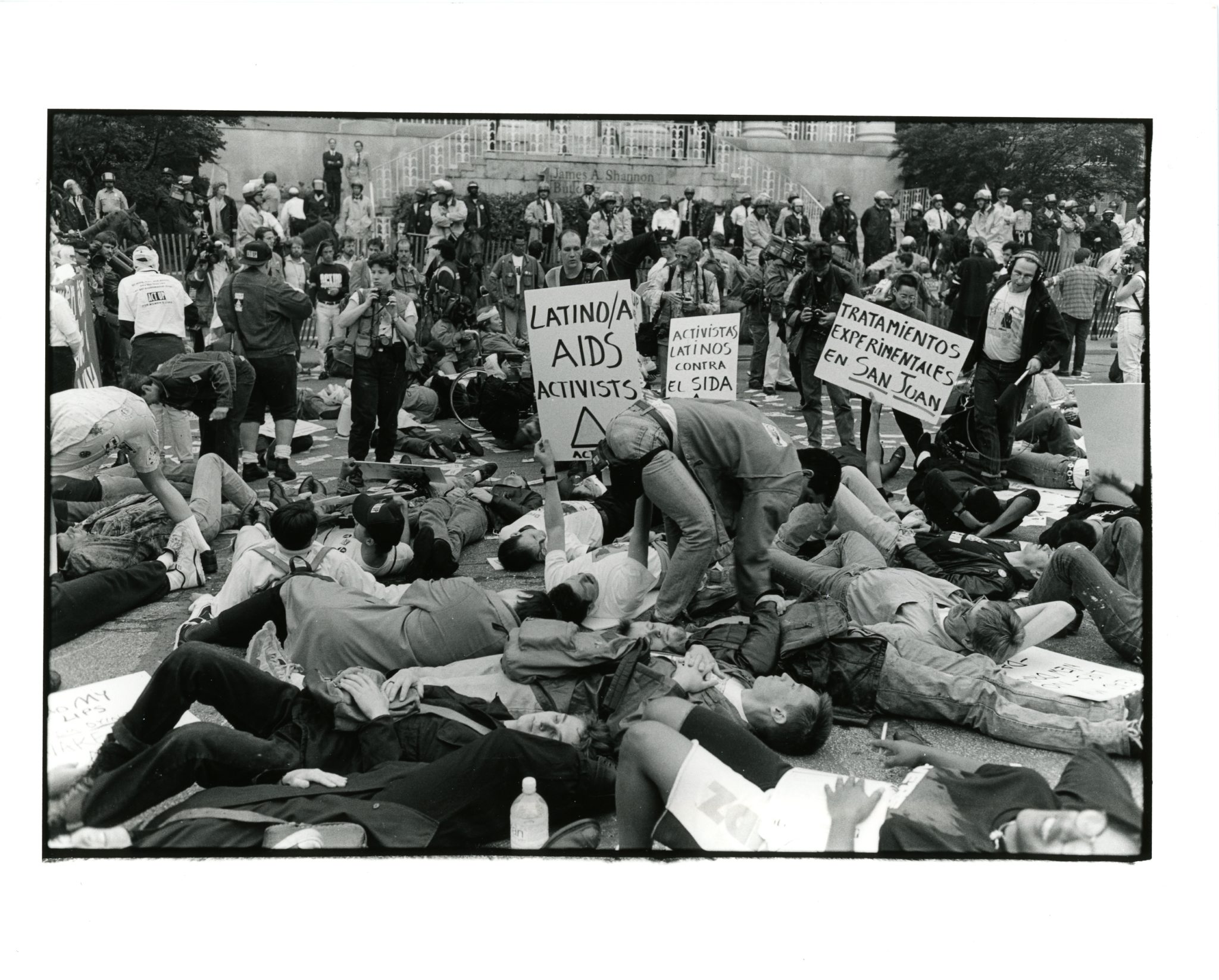

The Latino Caucus at the Storm the NIH action on May 21, 1990. Photograph by Dona Ann McAdams.

The Latino Caucus at the Storm the NIH action on May 21, 1990. Photograph by Dona Ann McAdams.

Another thing that struck me was how the actions were specifically organized, despite sometimes deviating from plans—with marshals and civil disobedience training and legal support.

Well, I do show that direct action historically, really was inherited from the civil rights movement.

I think that a lot of us in ACT UP were born in the ‘60s. We grew up seeing the Black civil rights movement using direct action and nonviolent civil disobedience on television or we saw it in Life magazine. Many of us had families that were involved in those movements.

What did you find in your research that hasn’t received enough attention?

One of the really big scoops in the book is the chapter on Dr. Joseph Sonnabend, who just passed away, unfortunately. Through the Freedom of Information Act, he got the paperwork on the Burroughs Wellcome AZT trial [the first anti-HIV drug marketed]. This was the trial that found that AZT worked, and then made AZT the highest profit-making pharmaceutical in history.

And he shows, by examining the trial, that it did not work, and the trial was corrupt. I think that this is something that should be on the front page of the New York Times. It’s an incredibly important story.

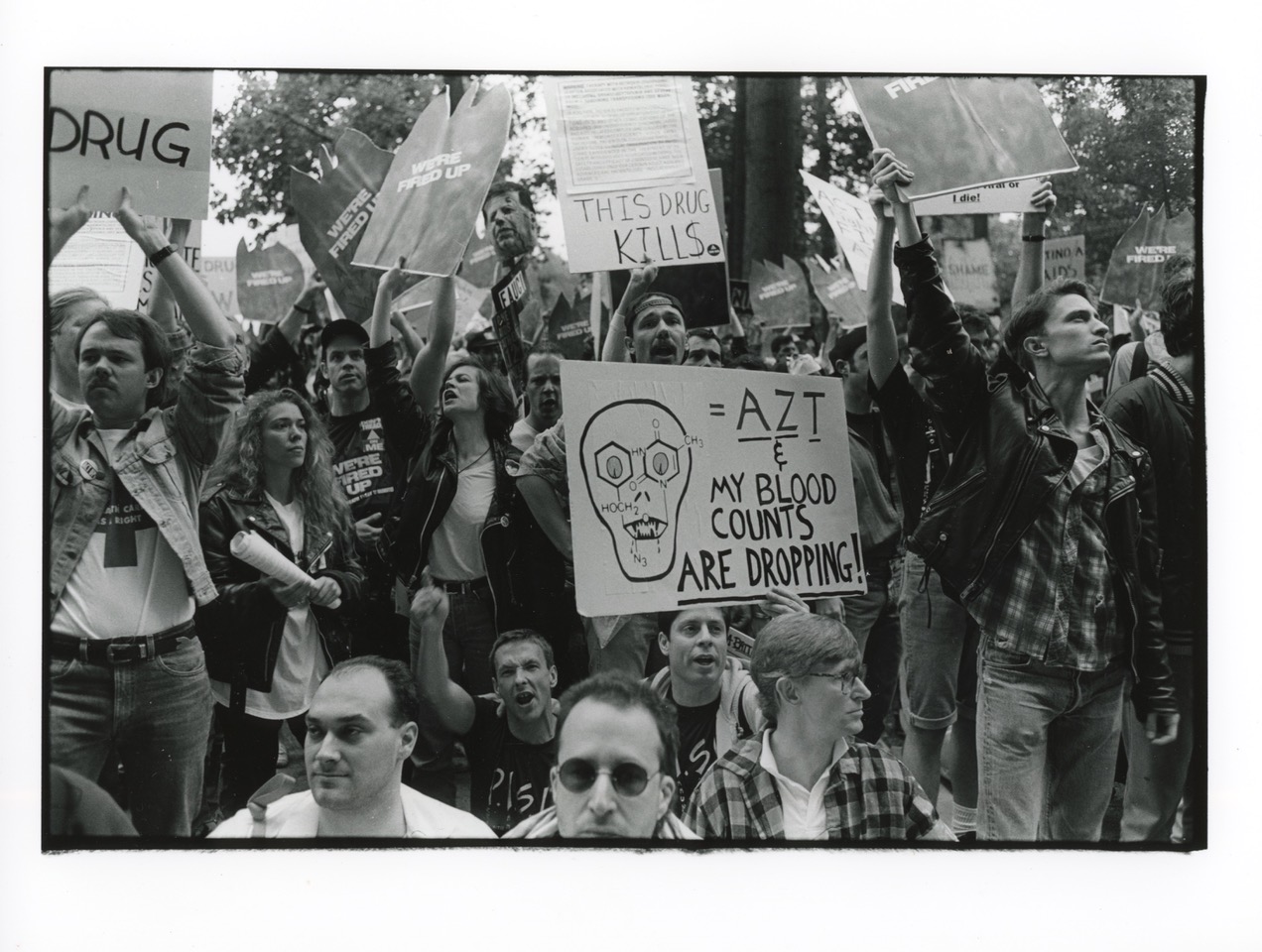

The Storm the NIH Action on May 21, 1990. From left to right: Mark Bronnenberg, Bill Monahan (obscured), Maria Maggenti, Phil Montana, Heidi Dorow. Far right with sign: Rand Snyder. Front: Tim Powers, Garry Kleinman. Photograph by Dona Ann McAdams.

The Storm the NIH Action on May 21, 1990. From left to right: Mark Bronnenberg, Bill Monahan (obscured), Maria Maggenti, Phil Montana, Heidi Dorow. Far right with sign: Rand Snyder. Front: Tim Powers, Garry Kleinman. Photograph by Dona Ann McAdams.

What did you learn that most surprised you?

When you really tally it, ACT UP was involved with basically every community that was vulnerable at the time. I mean, working with Haitian homeless people in finding housing. On every level, ACT UP was there—and it’s really important to understand that that is not just five guys [who are featured in other books and documentaries on the group].

Movements work in coalition—and that’s crucial information for anybody who wants to make change in America.

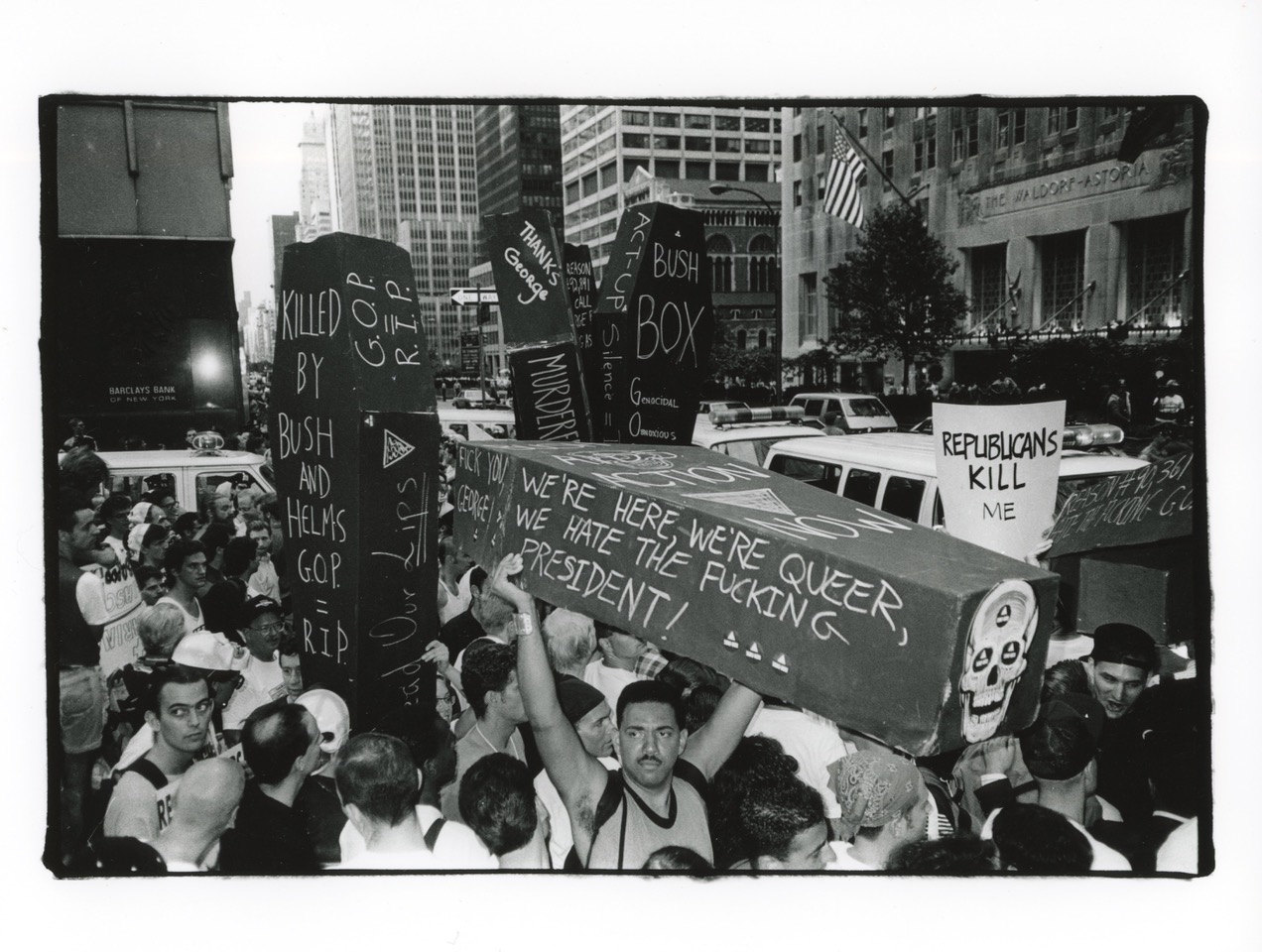

Top photograph by Dona Ann McAdams of an ACT UP demonstration at the Waldorf Astoria in 1990. Carrying the coffin is Assotto Saint.

All photographs are courtesy of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, the publisher of Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993 by Sarah Schulman.

Show Comments