In the summer of 2016, the synthetic cannabinoid “K2” burst into the drug landscape in Austin, where I was working in an emergency room on mercilessly humid weekend nights. A Google search of this then-unfamiliar drug told us it was “synthetic cannabis,” but what we saw patients experience in the weeks that followed seemed to be something else entirely.

The composition of K2 seemed to be in constant flux. One week would bring patients in the grip of frightening hallucinations; the next, severe low blood pressure that sent some of them to intensive care. Other weeks we might see mania, or hives or elevated acid levels in the blood. We were concerned. We still are.

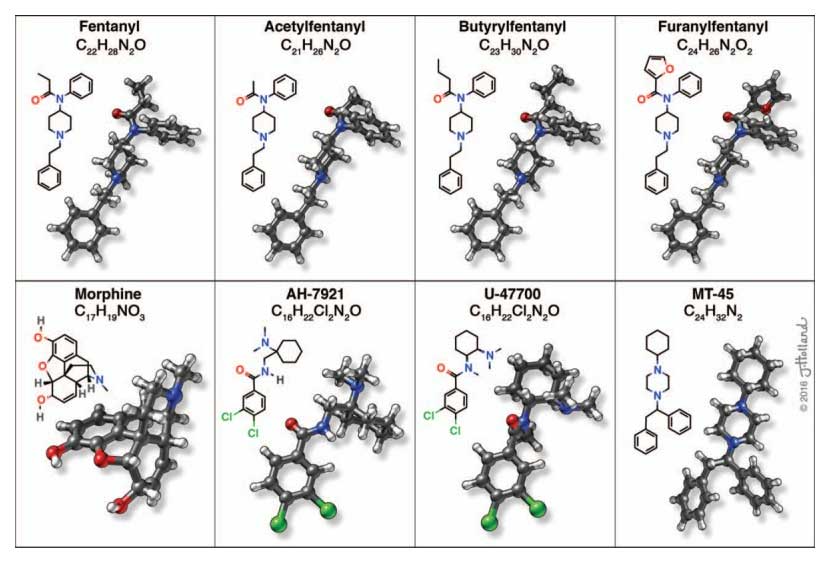

The past few years have seen a precipitous fall in the availability of unadulterated heroin in North America, increasingly mixed with, or outright replaced by, an ever more diverse array of molecules. These include not only a dozen variants of fentanyl, but benzimidazole-based drugs like isotonitazene and etonitazene; benzodiazepines like etizolam; and odd ducks like the veterinary sedative xylazine. Prohibition breeds innovation.

Law enforcement and legislators play Whac-a-Mole with each new substance as it emerges. The chemicals, supplies and physical space needed to manufacture synthetic drugs become carefully watched as well. Ingredients of choice get noticed, their purchase regulated and tracked. And their manufacturers get pushed further into the margins, forced to use less desirable and more dangerous options.

This is how people end up producing drugs under tarps in the woods instead of in a clean lab space. Using processes that create hazardous by-products. Handling chemicals that are carcinogenic or toxic. Safety measures enjoyed by above-ground chemists, like emergency showers and ventilated hoods that protect from splatters and explosions, are a luxury. And as profits take a hit and labor becomes more risky, people increasingly turn to a logical way to stretch the product: cutting it, with a substance that is cheaper, more potent or both than the substance it will later be marketed as.

We are seeing the supply chain not just change, but splinter.

The number of banned but still readily available drugs in the United States used to be finite. The handful we did have (heroin, for instance) were fairly well understood, their effects familiar. The medical guidebook for treating someone who overdosed on heroin or overamped with meth is well known. But now, patients are arriving with unfamiliar and dramatic presentations that aren’t readily found in textbooks.

We are seeing the supply chain not just change, but splinter, in ways that go beyond even the novel synthetic opioids linked to rise in overdose. COVID-stretched health care workers’ ongoing ignorance of the current supply is a recipe for disastrous misdiagnosis.

Levamisole, a veterinary deworming medicine, is widely used as a cutting agent for cocaine because it’s inexpensive and easily sourced. With repeated use, levamisole chokes the human body’s ability to make the white blood cells that protect us from infection. The early symptoms of this condition are vague enough—aches, fever, chills, malaise—that clinicians often mistake it for the flu. If it worsens, patients can present with rapid breathing and heart rate, become disoriented and even die without treatment.

Xylazine, a non-opioid veterinary sedative, has been increasingly devastating communities of opioid users by turning the supply into “tranq dope.” It can also open up painful skin ulcers and cause perplexing effects like severe anemia.

Codeine, being one of the less-hawkishly regulated opioids, is sometimes found in what’s sold as heroin. But codeine, as I learned after caring for a patient who’d used what he thought was heroin, often causes a reaction similar to a severe allergy when injected—which is why in clinical settings it’s not administered through an IV. But nothing’s protecting injection drug users who don’t realize codeine is in their supply.

And of course there’s fentanyl. Largely confined to heroin for most of the 2010s, it has over the past few years begun surfacing in cocaine and counterfeit pressed pills (like fake Xanax) and just about every prohibited substance that is not marijuana. The rules have changed.

Excited to share that the labor of love that is our textbook "Treating opioid use disorder in general medical settings" is officially published. Thanks to the incredible scholarship of the all-star 🌟 author line-up, it was a joy to edit their work 🧵 https://t.co/qFUGsZpvH1

— Sarah Wakeman (@DrSarahWakeman) September 14, 2021

Of course, the best way to keep people who use drugs safe is to simply legalize all drugs, regulating their production the same way as the drugs you get from a pharmacy. When you buy ibuprofen, you’re buying something that’s been subject to federal manufacturing standards to ensure it contains no contaminants—reaction by-products, dirt, bacteria and of course other drugs. Prohibition denies people that protection.

This idea is not an appealing one for many people who hold positions of power, including those who dictate how and where overdose response funding gets allocated. But as health care workers—as people who hold positions of power within spaces that are notoriously hostile toward drug users—we can learn to protect more patients from more harms.

We must decide that building up our knowledge is a priority.

Harm reductionists have created a number of educational resources that can help improve care of people who use drugs—on synthetic opioids; on reducing health care stigma; on common misconceptions; on accessing and administering naloxone, which is still effective against novel synthetic opioids whether or not we recognize their names.

To enact real progress, we much face our implicit (or explicit) biases against people who use drugs and ensure that when they access the health care spaces we work in, they are treated humanely. We must acknowledge that prohibition is filling our exam rooms with more people sick in more ways we weren’t expecting—and decide that building up our knowledge is a priority.

Photograph via National Institute on Drug Abuse

Show Comments