In July 2016, three Nigerians and one Indonesian were ferried to Nusa Kambangan, known as the “island of flowers,” off the coast of Java. A prison there, the so-called “Alcatraz of Indonesia,” holds people awaiting execution. Freddy Budiman, Humphrey Jefferson Ejike, Michael Titus Igweh and Seck Osmane, who had all been convicted on drug charges, were executed by firing squad.

Four hundred and fifty people are currently held on death row in Indonesia. The majority are there for drug convictions.

“Indonesia still has 13 kinds of crimes that are punishable by death,” Aisya Humaida, a human rights lawyer and activist in the country, told Filter. “The top three are narcotics, murder and terrorism.”

Her blunt explanation of why drug convictions trigger capital punishment? “War on drugs.”

“Drugs become the tool to prove how powerful the Indonesian leader or other key persons are.”

The country’s aggressive drug war has repercussions far beyond the firing squad. “This situation leads to prison overcrowding, caused by the high number of people who use drugs.”

And as with other aspects of the drug war, there are political motives behind Indonesia’s executions. “Drugs also become the tool to prove to the public how powerful the Indonesian leader or other key persons are,” Humaida observed.

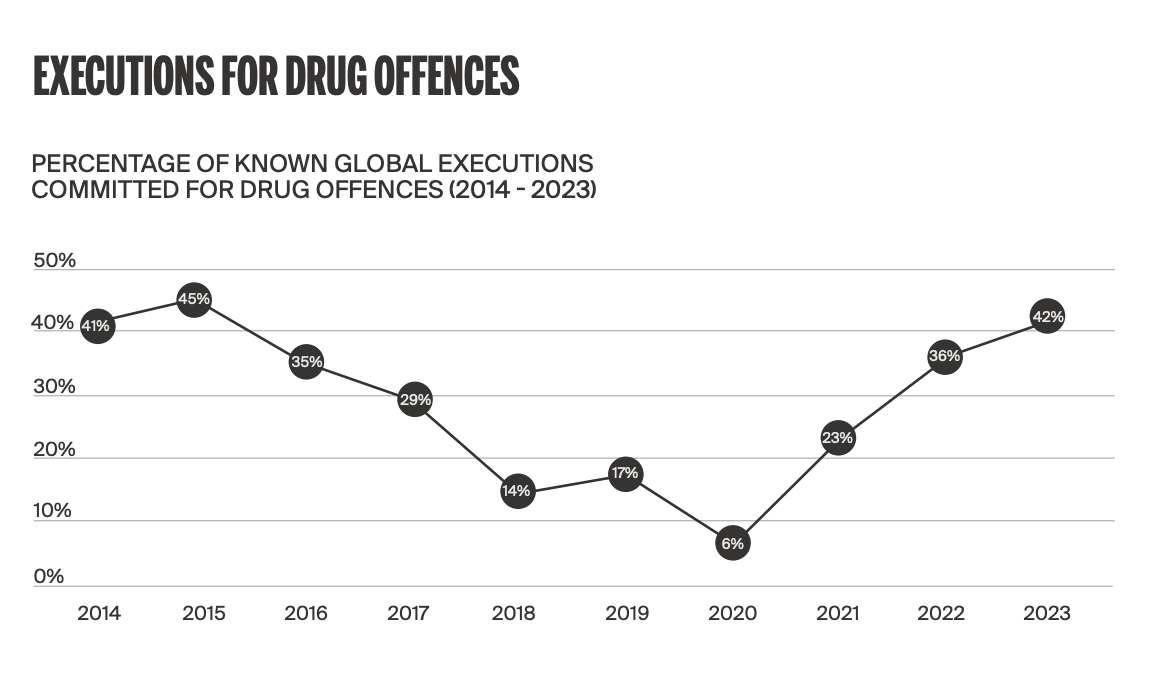

Since 2020, several countries have struck down provisions that allow or even require the death penalty for drug convictions such as trafficking. Yet such executions have still risen to a new global high, according to a report by Harm Reduction International (HRI).

The report—“The Death Penalty for Drug Offences: Global Overview 2023”—finds that at least 467 people were killed in 2023. That’s the highest number recorded since HRI began issuing these regular reports in 2007. The latest figure represents a 1,450 percent rise since 2020—a year when executions fell sharply, as the pandemic took hold—and a 44 percent increase on 2022.

“Despite how shocking this is, it’s not even a complete picture.”

Drug convictions led to 42 percent of the world’s executions in 2023—the highest proportion of that total since 2015, notes HRI, which “opposes the death penalty in all cases without exception.”

And by the end of a year in which 375 new death sentences for drugs were confirmed—a 20 percent increase on 2022—at least 3,000 people, in 19 countries, were on death row for drug convictions.

And by the end of a year in which 375 new death sentences for drugs were confirmed—a 20 percent increase on 2022—at least 3,000 people, in 19 countries, were on death row for drug convictions.

Ajeng Larasati, a human rights and public health specialist with Harm Reduction International, stresses that the total numbers in the report are undercounts. “Despite how shocking this is, it’s not even a complete picture,” she told Filter.

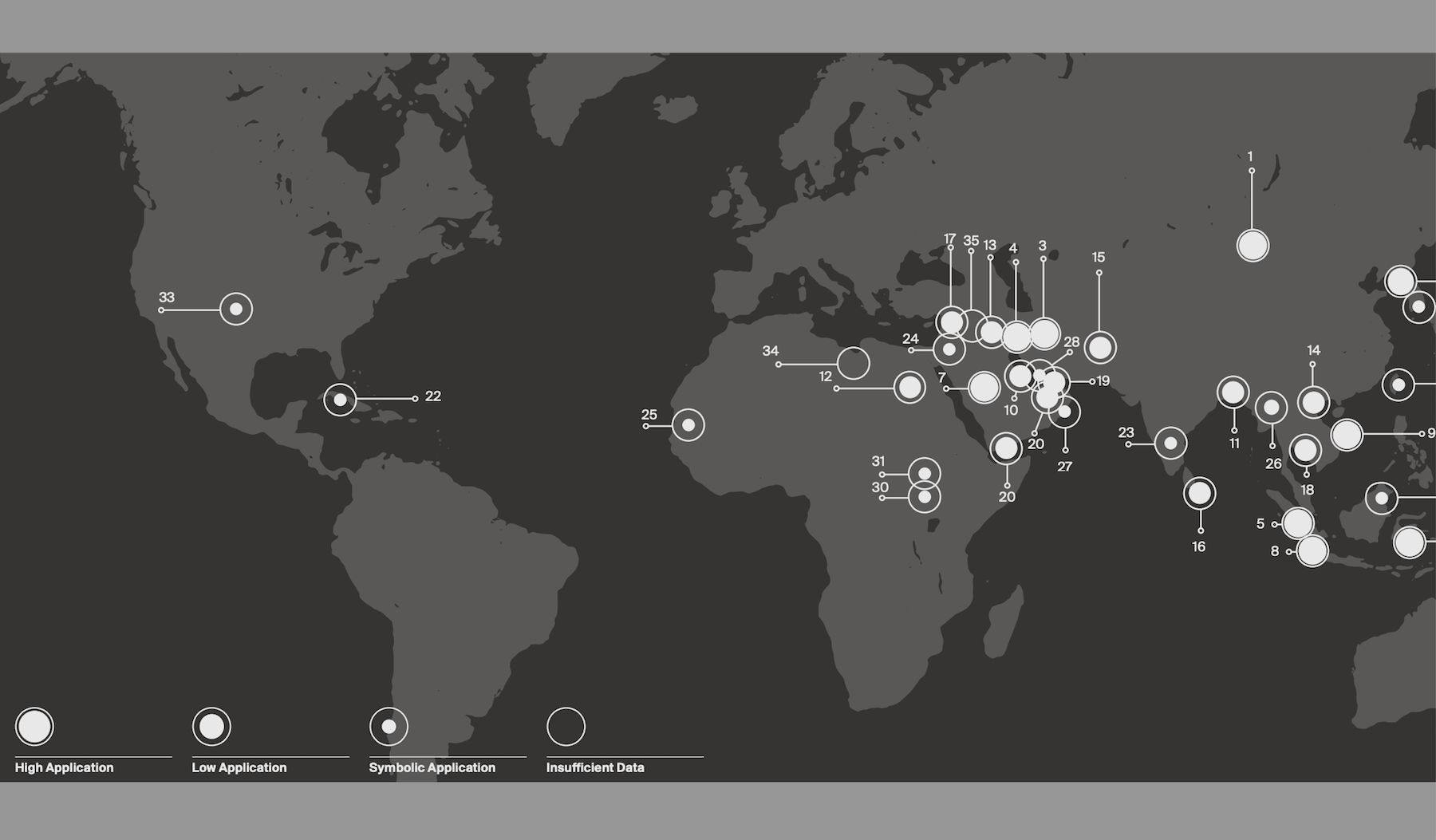

Five countries—China, Kuwait, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Singapore—are confirmed to have carried out executions for drugs in 2023. But China and Saudi Arabia don’t reveal their totals. And at least two more countries—North Korea and Vietnam—are “assumed” to have carried out such executions, according to the report, but “state secrecy and censorship … prevent confirmation of a minimum figure.”

“Drug executions are used to stifle upheaval.”

One theory Larasati has about the increase is growing use of drug crackdowns to snuff out political dissent. That might explain Iran’s increased numbers. Iran was responsible for the vast majority of confirmed executions for drugs in 2023: at least 459, up from 256 in 2022. The September 2022 killing of Mahsa Amini in police custody—she was accused of inappropriate head covering—sparked protests there.

“Drug executions are used to stifle upheaval,” Larasati said.

She also pointed to “the failure of the international community to hold states accountable.” If bodies like the United Nations “keep silent and don’t do anything” about executions for drugs, she continued, national governments “are allowed to do this, with no consequences. So why stop? No sanction, no penalty, for continuing to execute people for drug offenses.”

Cruel sentences other than death, up to and including life imprisonment for drug convictions, have also increased, Larasati emphasized.

Kuwait’s single execution for drugs in 2023 was the country’s first since 2007, in “a significant step backwards,” notes the report. But in a rare hopeful sign, the number of countries that keep the death penalty on the books for drug convictions—currently 34—is one lower than in 2022.

In July 2023, Pakistan’s Control of Narcotics Substances Act abolished use of the death penalty for drug convictions. It was the first country to do so in “over a decade,” notes HRI.

What spurred Pakistan’s government to revoke the death penalty for drugs?

Haris Zaki, an advocate with Justice Project Pakistan, told Filter that even before this decision, convictions like murder and terrorism far more commonly triggered an actual execution. “But people still spent decades on death row for drugs.”

What spurred Pakistan’s government to revoke the death penalty for drugs? According to Zaki, it was a trade deal regarding textiles with countries in the European Union, which requires the country to conform to certain human rights standards.

Zaki described how the government had previously abolished the death penalty for other laws that he termed “low-hanging fruit”—like colonial-era laws concerning “train sabotage” or “stealing teacup sets from a train”—but eventually came around to drug convictions.

There was no fanfare. Zaki said the decision was so low-key that there are still judges who are confused about it.

Though Pakistan has seemingly ended one of the worst abuses of its drug war, Zaki’s organization has a great deal more work to do.

“There is an urgent need to counter over-incarceration for drug offenses and improve access to health/treatment for prisoners jailed for drug use, through the implementation of human-rights based sentencing guidelines and improved standards of health care in prisons,” a paper published by Justice Project Pakistan stated.

“Drug laws, policies, and drug control and treatment practices often do not take into account the right to the highest attainable standards of health and the need for voluntary access to harm reduction services and drug dependence treatment,” the paper added. Alternatives to incarceration, such as compulsory treatment, also cause harm, it noted—as does a lack of harm reduction measures, particularly in overcrowded prisons.

“There’s still a strong stigma around drugs,” Zaki said. “Some people have strong feelings.”

Top image, indicating countries that retain the death penalty for drug convictions, and inset graph are taken from “The Death Penalty for Drug Offences: Global Overview 2023,” by Harm Reduction International.

Show Comments