A one-size-fits-all approach to the “opioid epidemic” will not work, say researchers at Iowa State University. Co-authors David Peters, Shannon Monnat, Andrew Hochstetler and Mark Berg found that there are actually four distinct, overlapping opioid-involved overdose crises, varying by geographic region and local socioeconomic factors. Policy responses should be tailored to each city or community and their unique challenges, they say.

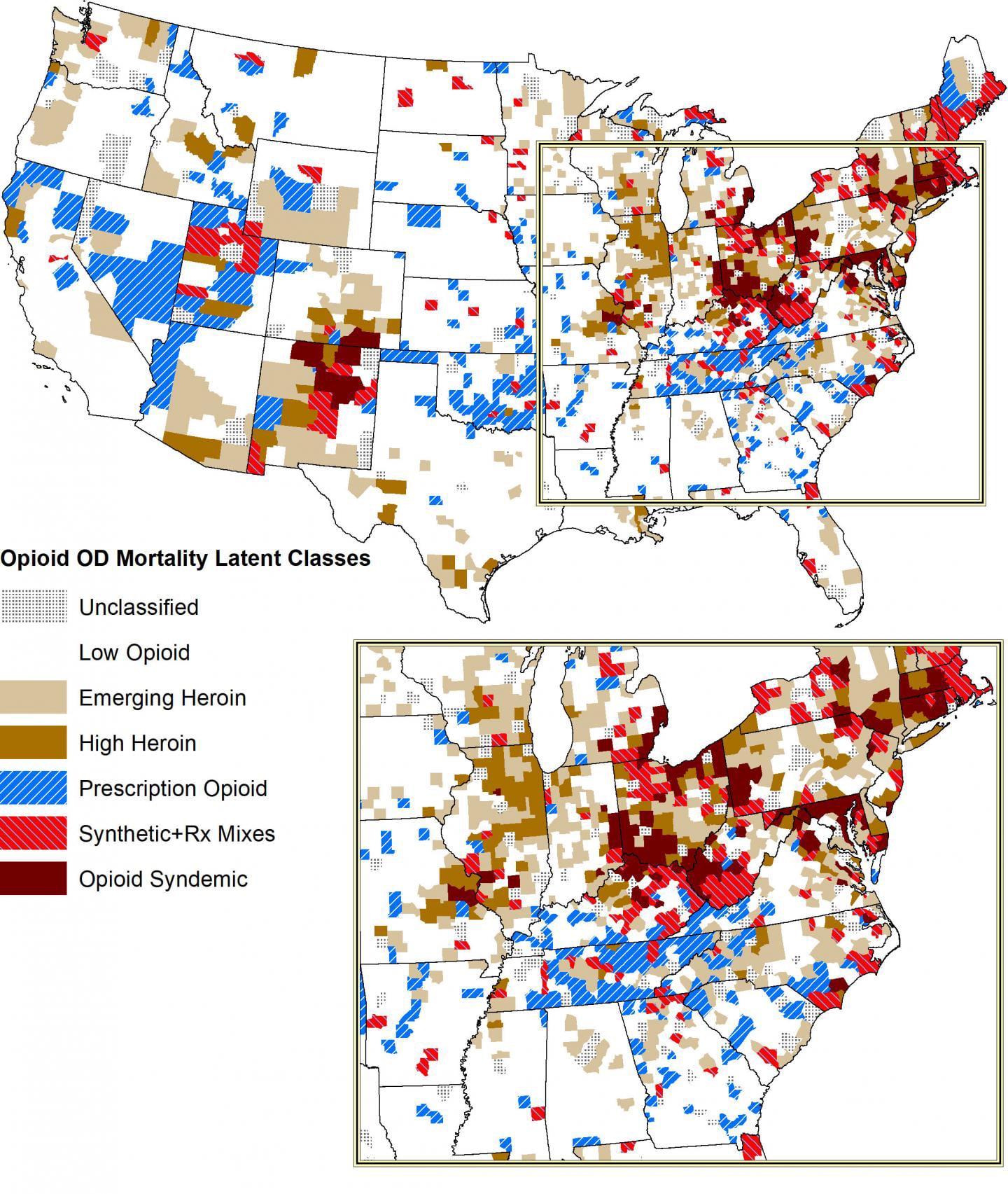

The study, published in Rural Sociology, analyzed county-level death certificates throughout the US that listed opioid overdose as a cause of death. (You can view the map illustrating the data here.) It describes the four crises as follows:

An illicit “prescription” drug crisis that affects rural Southern states, years after prescription drug-involved overdoses peaked nationally in 2013. Many former mining and manufacturing workers in these regions experience disability and chronic pain. The researchers say that after new restrictions were placed on prescription opioids, illicit manufacturers have been creating combination drugs, like oxycodone or hydrocodone mixed with more potent synthetic opioids like fentanyl.

A heroin crisis that affects areas in the West and Midwest. The study found heroin-involved overdose deaths correspond geographically with known cartel trafficking routes along interstate highways between major urban centers. They identified one key route between El Paso, Texas and Denver, Colorado; and another going from Texas through Oklahoma to St. Louis, Missouri and on to Chicago, Illinois.

A synthetic opioid crisis that affects Northeastern cities and parts of Utah and New Mexico. Common illicit drugs such as heroin and cocaine are frequently mixed with potent synthetic opioids like fentanyl.

And finally, a “syndemic” where multiple aspects of different crises overlap. This involves people who use many different kinds of opioids, prescription or illicit, as well as other drugs. The study identified this phenomenon as particularly pronounced in regions like the Ohio River Valley and states like Ohio, West Virginia, Indiana and Kentucky, which first experienced prescription opioid-involved death crises in the 1990s. It also found syndemics in states like Massachusetts and New Hampshire that experienced heroin crises in that decade. It found these syndemics correlate with states that have suffered high unemployment and job loss from the mining and manufacturing sectors.

The implications of all this? “Any single opioid response by a state or federal government is going to be inadequate,” Peters said. “You need to have specific strategies based on the specific drug and location. For example, better regulation of prescription opioids by states will have no impact on heroin deaths or synthetic deaths because drug trafficking organizations bring these drugs in from Mexico.”

“It’s clear that the prescription epidemic is driven by work disability, poverty, and economic decline,” he continued. “To address the drug problem in prescription places, it’s about poverty reduction and economic development. Whereas in heroin-impacted communities, the response ought to be more traditional law enforcement. Drug interdiction, dismantling drug trafficking organizations, and targeted treatments to specific sub-populations.”

Drug policy reform advocates will hotly object to that prohibitionist recommendation.

“If traditional law enforcement was an effective to tactic for ‘dealing with’ urban heroin use, we wouldn’t be in the current crisis that we see across the country,” Kat Humphries, program director at the Harm Reduction Action Center, told Filter. “Too many people are struggling with mental health issues, housing instability, and systemic racism for us to police away the issue of problematic substance use. Until we address the reasons why people turn to highly stigmatized substances as a coping mechanism (in urban or in rural settings), we will continue to see significant fatality related to drug overdose.”

Instead of seeing “drug dealers” as a threat to be eliminated through law enforcement, state and local governments may in fact find that people who sell drugs have much valuable information to offer them in the fight to reduce overdose deaths. Having a clear picture of how people in communities use drugs will inform better responses to local trends.

“One place to start is to talk to local drug users to ensure your data is accurately depicting the community,” said Humphries, who has written for Filter. “Because of the history of stigma between healthcare providers and people who use drugs, often times data collected by health departments and health researchers will miss important details about trends in drug use. Working with gatekeepers in drug using communities is essential to an accurate picture of use and determining the best course of action forward.”

Yet the research is valuable because policy-makers and advocates should surely be aware of unique local patterns in substance use, overdose and drug supply. At the same time, tailored responses should universally be accompanied by interventions that will benefit everyone—like education about using naloxone, safe consumption spaces and drug checking or fentanyl strips.

People everywhere use drugs in unique and ever-changing ways that defy easy categorization. For example, Filter reported previously on a concerning trend of drug overdoses in Marion County, Indiana linked to both fentanyl and stimulants like methamphetamine and cocaine. Local experts and researchers were puzzled by the unusual pattern. Deaths linked to prescription opioids and heroin were declining, while the fentanyl-stimulant overdoses were increasing. Researchers didn’t even know whether people were intentionally combining these drugs or if their supplies were unknowingly contaminated.

State governments and cities don’t have the ability to effectively stop trafficking organizations from bringing drugs in, as decades of drug war experience have shown—but they do have tools to respond effectively to the public health consequences.

Image courtesy of Iowa State University.

Show Comments