On April 12, the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) formally designated xylazine, in combination with fentanyl, an “emerging threat.” It marks the first time a US administration has singled out an illicit drug—or in this case, a mix of two—in this way. It also means xylazine is about to become much more heavily surveilled.

The federal designation has existed since the implementation of the Preventing Emerging Threats Act of 2018. Congress designated methamphetamine an “emerging threat” in 2021, but the White House has not exercised its authority until now.

The ONDCP’s 2024 budget request will include $11 million to monitor and address “emerging threats.” This will inevitably lead to increased crackdowns on xylazine-associated supply chains, as well as fearmongering publicity campaigns by the Drug Enforcement Administration.

“What’s frustrating is the hysteria that sometimes comes with these big announcements,” Maritza Perez Medina, director of the Office of Federal Affairs at the Drug Policy Alliance, told Filter. “The scare tactics are problematic. They create more stigma for people who use drugs, and they all detract from conversations that should be based in public health.”

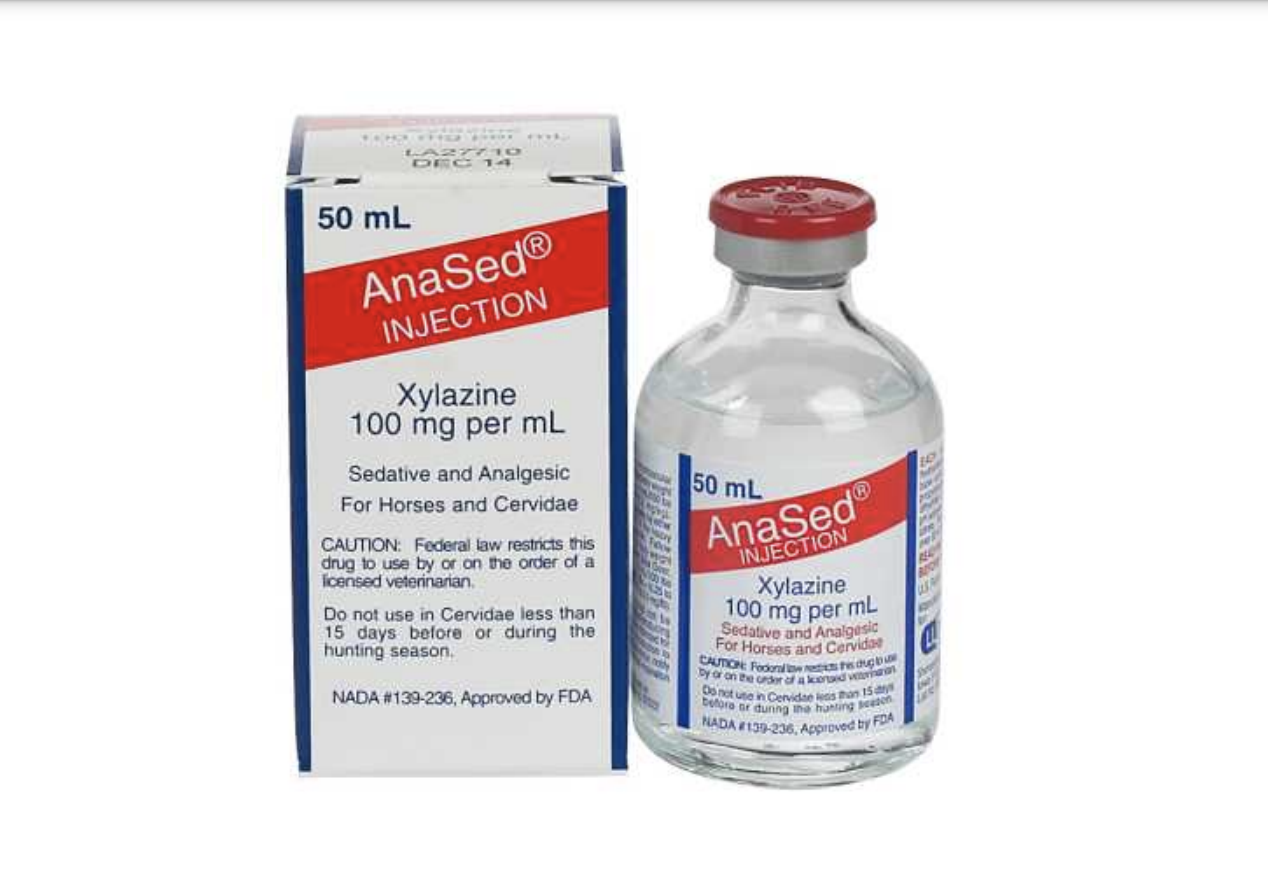

Xylazine is a Food and Drug Administration-approved veterinary tranquilizer, which in recent years has been increasingly cut into the illicit opioid supply in an attempt to make fentanyl a closer approximation of actual heroin.

Fentanyl on its own peaks fairly quickly, leaving many people with opioid tolerance facing withdrawal again two or three hours later. The effects of xylazine can last twice as long, and the right balance of the two can stretch out the fentanyl, i.e. “give it legs.”

But xylazine can cause a litany of adverse effects, including sudden, protracted blackouts, and soft-tissue infections that can turn necrotic and linger for years without healing. In an increasingly fractured illicit drug market where most people don’t know what they’re using or in what quantities, many who use opioids are left vulnerable to these effects.

“The people who end up being hit the hardest are those on the lowest end of the drug distribution chain.”

“There’s already a lot of fear around fentanyl. Understandably so … it’s a scary time to be a drug user,” Perez Medina said. “But when you [criminalize something] the people who end up being hit the hardest are those on the lowest end of the drug distribution chain. Usually people of color.”

In February, the FDA placed restrictions on the importation of both xylazine and its individual active ingredients. In March, a bill to regulate xylazine under Schedule III of the Controlled Substances Act was introduced to Congress. This would place xylazine alongside substances like ketamine, testosterone and buprenorphine (Suboxone). ONDCP Director Rahul Gupta has indicated that he’s supportive.

ONDCP can recommend that xylazine be federally scheduled, but ultimately doesn’t have the authority to do so itself. That lies with the Health and Human Services Department and the Department of Justice, or, alternatively, with Congress. These two routes are independent of one another, so it’s conceivable they could be undertaken at the same time.

Xylazine has devastated many drug-user communities. However, the ONDCP announcement cited data on xylazine-involved deaths in a way that is deeply misleading.

The processes by which post-mortem toxicology data is collected varies wildly from state to state.

“The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) reports that: Between 2020 and 2021, forensic laboratory identifications of xylazine rose in all four US census regions, most notably in the South (193 percent) and the West (112 percent),” the announcement stated. “Xylazine-positive overdose deaths increased by 1,127 percent in the South, 750 percent in the West, more than 500 percent in the Midwest, and more than 100 percent in the Northeast.”

This is a mess. First, “xylazine-positive” deaths include cases where xylazine was identified, but not found to be a cause of death; it’s a separate classification from “xylazine-involved” deaths.

Second, percentages are not numbers. The 750-percent increase in the West, for instance, refers to an increase from four deaths in 2020 to 34 deaths in 2021.

Third, these increases need to be understood in the context that the processes by which post-mortem toxicology data is collected varies wildly from state to state. More specifically, some state medical examiners don’t test for xylazine if fentanyl is found first—once it is, they stop looking. In general, though, so-called “hotspots” for any given drug are going to skew toward the places that happen to have the resources to look for them.

“Testing for xylazine is uneven across the United States, which makes it hard to get the national picture. Many communities are not even aware of this threat in their backyard,” Gupta told White House reporters on April 12.

Gupta is not aware of whether or not xylazine is in their backyard either. But the federal resources unlocked by the “emergent threat” designation probably won’t prioritize public drug-checking, which is the kind that’s useful to people while they’re still alive.

Photograph via Office of Science and Technical Information

DPA previously provided a restricted grant to The Influence Foundation, which operates Filter, to support a Drug War Journalism Diversity Fellowship.